When the Civil Rights Association was established in 1967, a few older republicans were against the idea.

They argued that if we achieved democracy and equality, the impetus to destroy the northern state would disappear. They believed that only continued unionist discrimination could generate enough militant support to discredit and ultimately dismantle the state.

Fast forward over 50 years and we may witness a somewhat similar conflict of ideas after the forthcoming election. If Sinn Féin becomes the largest Stormont party, will a majority of nationalists settle for sectarian triumphalism within the state, rather than try to demolish it?

There is some evidence they might. This paper’s recent opinion poll showed that although the SDLP and Sinn Féin command 38 per cent support, backing for a united Ireland hovers at around 30 per cent. The rising tide of nationalism is not necessarily floating the boat of Irish unity.

Part of the explanation may be that no one is quite sure what a united Ireland means. It remains a theoretical state towards which current nationalist politicians aspire, confident in the knowledge that they will probably never get there to have to devise its intricate details.

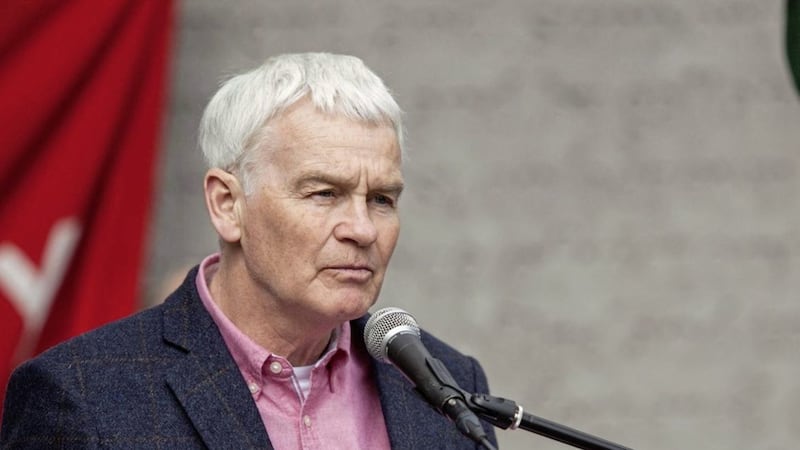

Former hunger striker, Tommy McKearney, made that point in Carrickmore on Easter Monday. He said that a united Ireland is “too vague in meaning”, allowing the term to be used for political effect, without any obligation to pursue it.

If, for example, unity were to mean the end of the north’s NHS system, support for a united Ireland falls to 23 per cent. So it appears reasonable to assume that nationalism’s electoral progress is based more on anti-unionist sentiment than on some wider national ethos.

In addition, the preservation of Stormont will allow SF to enjoy the sectarian certainty of the perks and privileges of perpetual power. A united Ireland is likely to offer significantly more electoral competition and require a different calibre of candidate.

The traditional argument for Irish unity was that the Irish nation warranted an Irish state, with a national flag representing those of all religions and none. However, in 1998 nationalists said that unionists were British and switched their pro-unity argument from the Irish nation to economics.

Unionists (and obviously some nationalists) counter this by reference to the higher level of welfare and health care here. So if SF becomes the largest party in an administration, which at worst preserves the NHS and maybe even improves it, where is the demand for a united Ireland?

Unity is not just about joining the north and the south together in a single state. That’s the easy bit. There can be no united Ireland without a largely united north, but ingrained sectarianism renders that highly improbable.

The problem is not just unionism’s support for the connection with Britain, it also includes its opposition to union with Brussels. The SDLP and SF, however, will not countenance a united Ireland outside the EU. (So much for northern unity.)

Which brings us to a different election. France goes to the polls tomorrow. If Marine Le Pen wins, or does well, it may herald France’s exit from the EU, or at least a significant reduction in the EU’s centralised powers. In that case the protocol will be the least of the EU’s priorities, possibly meaning less EU backing for nationalism’s united Ireland dream.

So were the old republicans right? Did the success of the civil rights movement secure the future of the northern state? We do not know, because before most of the civil rights demands were granted, the Provisional IRA (conceived by some of those same old men) had begun a military campaign to destroy the state.

However, their war merely secured the state’s future. The Good Friday Agreement recognised the legitimacy of partition and created a new Stormont. If Sinn Féin becomes the largest party in that new Stormont, the hype over a united Ireland will be massive. But the reality may be somewhat different.