We need a better response to the Boris Bridge than unionists treating it as a wind-up and nationalists regarding it as an insult.

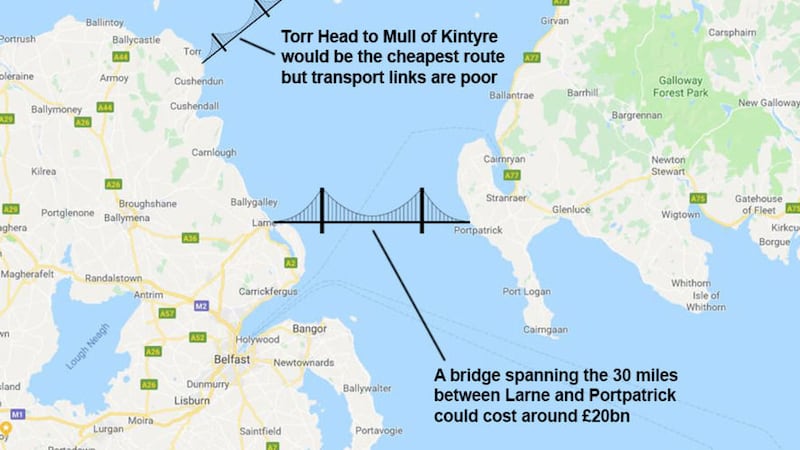

A fixed link between Scotland and Northern Ireland was mentioned again by the prime minister last week when he confirmed it will be part of an independent review into new UK-wide transport links, chaired by former Network Rail chief Sir Peter Hendy.

The Boris Bridge may not be a serious idea but it reflects a real chance for Northern Ireland to get its hands on some serious money.

The government intends to spend its way out of Brexit through a huge programme of national infrastructure investment. Johnson keeps suggesting a bridge because his trademark combination of flamboyance and laziness leaves him unsure how Northern Ireland fits into this. His theatrical ambition is in truth a form of insularity - primed with cash for road and rail, he has only one idea how that might span a stretch of water.

But the investment programme itself is no vague notion. It is a central plank of the UK Internal Markets Bill, notorious for threatening to break international law.

The bill would allow ministers in London to “provide financial assistance” for infrastructure anywhere in the country as long as it serves economic development, directly or indirectly.

Definitions are extremely broad: infrastructure includes housing; economic development includes social inclusion; financial assistance can be “in any form”.

In Scotland, the SNP is portraying this as a “power grab” on two grounds: London could intrude on infrastructure in the devolved regions, which is a devolved matter; and Westminster is not passing on all the related powers when it acquires them automatically from Brussels at the end of the Brexit transition period.

Both objections are pot-stirring spin: London’s plan is to offer more funding to devolved projects, not to take them over; on the former EU powers, how can something you never had be grabbed off you? A degree of national infrastructure regulation remains essential.

The SDLP, which controls Stormont’s Department for Infrastructure, has disappointingly decided to echo the ‘power grab’ line. At least this is a political position, however cynical. The DUP, which first proposed the bridge to pad out a manifesto five years ago, can barely manage a response beyond sniggering.

What all Stormont’s executive parties need to do is get in front of this wave of money and start proposing sensible ideas on how to spend it.

Obvious projects include improving our ports and airports and their associated road and rail links, abolishing air passenger duty, subsidising ferry routes and developing new marine technology, such as the Artemis zero emission ferry approved under the Belfast City Deal.

Northern Ireland’s worst cross-channel bottlenecks are actually in Scotland, making a national approach ideal to addressing them. For freight, the lack of motorway connections to Scottish ports is a problem on a par with the Brexit sea border. For passengers, perhaps it merely reflects consumer choice. But could high-quality boat-train services have a post-covid future? That question deserves to be in Sir Peter’s review.

These are only transport proposals. The urgent £2.5 billion cost of modernising Northern Ireland’s water and sewage system, which Stormont thought it had pinned down in January’s New Decade, New Approach deal, could be re-presented to London under the terms of the UK Internal Markets Bill.

Stormont could finally implement the Bengoa Report on NHS reform - health also counts as infrastructure under the bill.

If the SDLP and Sinn Féin dislike engaging with a programme that aims to bind the UK together, they can offset that concern by involving the Republic.

Northern Ireland depends heavily on the Port of Dublin for internal UK trade, while the Republic does nearly all its EU goods trade via England and Wales.

That encompasses road, rail and port links throughout ‘these islands’, to use the official Good Friday Agreement term. It brings in the EU, by involving trans-European routes eligible for the EU’s Connecting Europe infrastructure funds. With cooperation, the EU will help finance routes crossing non-EU countries.

Stormont could promote Northern Ireland’s infrastructure interests directly with London, Dublin and Brussels and through the North-South and East-West bodies of the agreement. At the British-Irish Council, involving every national and devolved government and with a remit to discuss EU issues, Stormont has been the lead administration on transport for the past 21 years.

If all we can extract from these opportunities is laughing at a bridge, the joke is on us.