Rishi Sunak’s promise to the British public was a straightforward one – he vowed to “stop the boats” as thousands of asylum seekers crossed the Channel without authorisation.

But as crossings continued, the pledge has been complicated by legal challenges arguing that forcibly removing migrants to Rwanda is against their rights and the law.

The Supreme Court delivered the Prime Minister a blow by ruling that his policy was unlawful.

Five of the UK’s most senior justices ruled the scheme could not go ahead as it was.

They cited a long list of concerns about Rwanda as they concluded there was a real risk that genuine refugees could be sent back to their country of origin, where they would face “ill-treatment”.

Now Home Secretary James Cleverly is travelling to Kigali where he will sign a fresh treaty as part of Mr Sunak’s goal of making the plan to send migrants to the African nation legally watertight.

– What is Plan B?

First, Rishi Sunak is pinning his hopes on soothing the court’s concerns by agreeing a new legally binding treaty with Rwanda.

He wants the deal to bind Kigali into not sending failed claimants to any other country in order to prevent “refoulement” – removing asylum seekers back to the country where they face persecution.

But it is unclear what legal status people who fail the process will have if they remain in Rwanda, but not as a refugee.

Mr Sunak said the treaty will commit the UK to “bring back anyone if ordered to do so by a court”, meaning some migrants sent to Kigali could be returned to the UK.

He will go further to reduce the chances of a court blocking the new treaty by bringing forward “emergency legislation” to ask Parliament to confirm it believes Rwanda is a “safe” country.

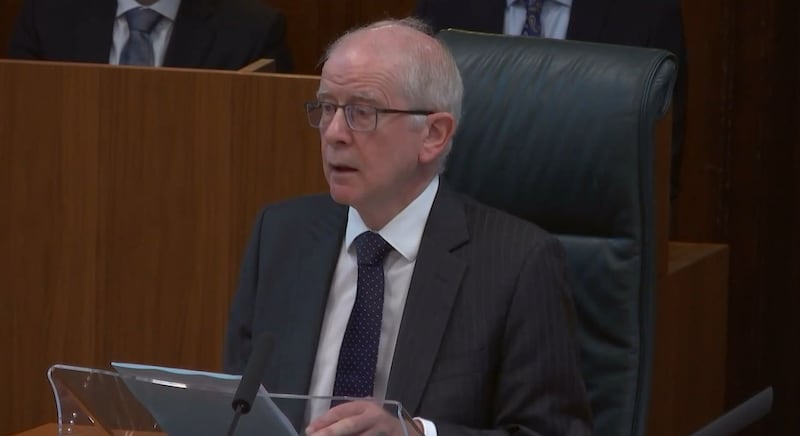

Supreme Court president Lord Reed and his four justices ruled there were “substantial” grounds to believe there was a “real risk” of refugees being returned to their home countries.

Inheriting the Rwanda headache as the new Home Secretary, Mr Cleverly said anyone removed to Rwanda could not be “sent to another country than the UK”, but officials made clear they did not expect people being returned to Britain.

Elevating the deal from a “memorandum of understanding” to a treaty that has been ratified by Parliament could strengthen it in the courts’ minds.

But not a penny of the £140 million already paid to Kigali can be clawed back, and the new treaty is expected to add to the cost.

– What problems must the treaty overcome?

The Supreme Court judgment highlighted a series of grave concerns about Rwanda that would need addressing before they could consider the policy lawful.

Refoulement was the chief concern, which the justices said was seen in a “similar” deal Rwanda had with Israel, and was continuing.

Evidence from the UNHCR, the United Nations refugee agency, showed there was 100% rejection for nationals from three war-torn countries between 2020 and 2022.

Home Office figures from the same period showed the UK granted 74% of cases from Afghanistan, 98% from Syria and 40% from Yemen.

The Supreme Court said there was “evidence of a culture within Rwanda of, at best, inadequate understanding of Rwanda’s obligations under the Refugee Convention”.

Evidence was presented that Kigali had a “poor human rights record”, citing British police warning Rwandans in the UK of credible plans by the nation’s government to kill them.

Concerns of political and media freedom were also raised, as was the inability of the Rwandan courts to act independently of the government.

The UNHCR suggested there had been more than 100 cases of refoulement after the UK agreed its deal with Rwanda.

– So, Plan C?

Facing calls from the Tory right to pull out of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), Mr Sunak offered a glimmer of hope.

He said he was “prepared to change our laws and revisit those international relationships” if they were still “frustrating” his plans.

But Mr Cleverly told the Commons he did not believe disregarding the ECHR or the Refugee Convention was necessary.

The Home Secretary made clear that the judgment was not contingent on the ECHR.

Today’s Supreme Court judgment is no surprise. It was predicted by a number of people close to the process. Given the current state of the law, there is no reason to criticise the judges. Instead, the government must introduce emergency legislation. 1/3

— Suella Braverman MP (@SuellaBraverman) November 15, 2023

Delivering the court’s ruling, Lord Reed made clear it was not just the ECHR that was relevant to the case, but other treaties such as the UN conventions against torture and its covenant on civil rights.

He cited three pieces of domestic legislation as binding the UK on the principle of non-refoulement and said the Human Rights Act gave effect to the ECHR.

– How soon will flights begin?

Even if the simpler treaty route was successful, it could take more than 40 sitting days to be ratified in Parliament. No 10 said the agreement could be laid in the House in the “coming days”.

But further legal challenges could halt flights again.

Navigating the legal minefield of amending multiple domestic laws would take months, at least, and disregarding international commitments could create a row with allies.

Downing Street was unable to say whether flights to Kigali would take off before the next election, which is expected within a year.

Mr Sunak said ministers are “working extremely hard to make sure that we can get a plane off as planned in the spring”.

But he repeatedly refused to commit that the first flight would take off before the next election.