Michael McConville was just nine-years-old when he and a group of friends became lost and wandered onto the Shankill Road in west Belfast during the marching season.

"We’re Catholics and we’re lost", he told a woman whose door he had knocked on for help.

Before long Mr McConville, who two years later would see his mother Jean abducted, beaten and threatened at gunpoint from their home, was enjoying cookies and lemonade.

That kind woman later brought him back to his "home" territory.

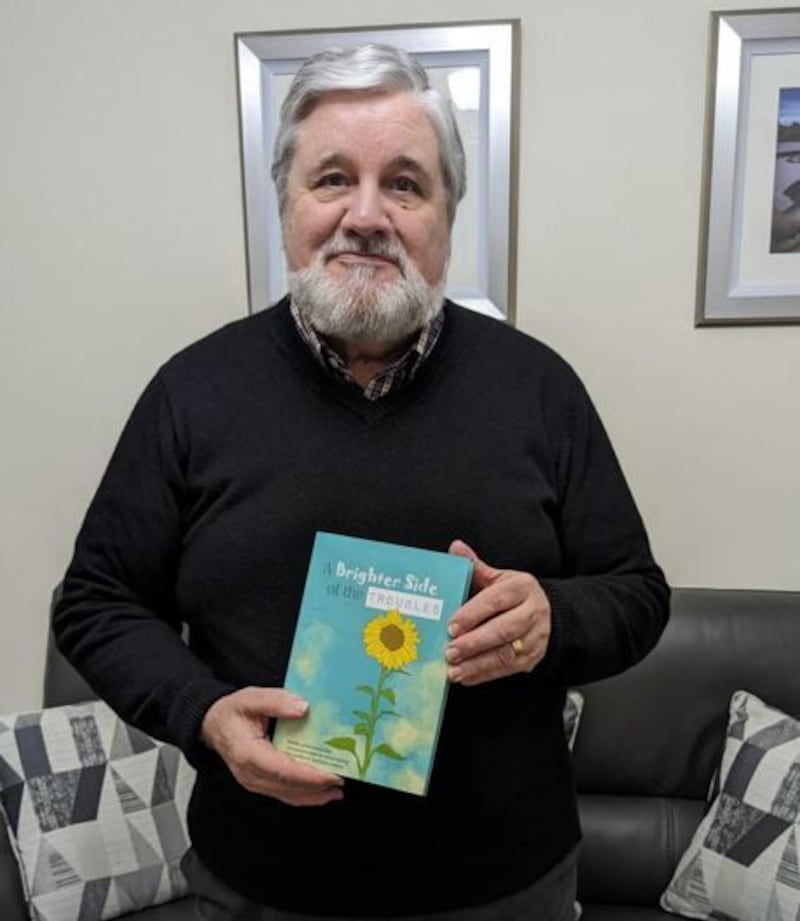

Mr McConville's story is one of those featured in a new book telling the many stories of the "brighter side" of the Troubles in Northern Ireland.

From personal tragedy to chance encounters and spontaneous acts of kindness and concern, 'A Brighter Side of the Troubles’ tells the experiences of more than 40 victims and survivors of the conflict.

Jointly edited by Alan McBride, who lost his wife in the Shankill bombing in 1993, and George Larmour, whose brother John was murdered by the IRA in 1988, the authors say they hope it will make readers "smile, rather than shed a tear".

Read more:

Alan McBride: Amnesty bill will not cause victims and survivors to forget past

Day of reflection event hears message of hope from sister of Disappeared victim

Published by the WAVE Trauma Centre, it will be officially unveiled by broadcaster Paul Clarke at an event in Belfast on Wednesday.

Among other stories featured is that of Jennifer Donnelly, who tells of unrest in her community amid the hunger strikes with paint and petrol bombs being thrown.

She recalls how a "local priest who had obviously seen enough death and pain, decided enough was enough".

"He strode towards the young men, admonishing them for trying to injure or maim fellow humans, asking where all the pain will end if we keep up the tit-for-tat violence," she said.

"As he reached the first crate of bottles filled with petrol and paint, he reached down and grabbed the bottles and proceeded to empty them onto the grass.

"He emptied several crates worth of these bottles as the young men of the estate stood bemused at his actions.

"After this had calmed down and the priest had returned to his house, some of the more hardline men in the area went to him and having noticed his sleeve had been splashed with petrol from emptying the bottles earlier, they set his sleeve on fire as a punishment or warning to stay out of their business.

"I understood even at my young age that even a priest would be in trouble for these actions.

"It’s how these people control their local area on both sides of the divide, but the actions of this priest also taught me that the violence has to end somewhere."

Another story is told by Alan McBride's daughter Zoe, who lost her mother when she was two. She tells of how her school teacher helped her father in a "simple practical gesture".

"Little girls like to be imaginative with their hair and I was no exception but Dad couldn’t do it," she recalled.

"He did try, bless him, but it was always a disaster, getting to the last strand of hair in a plait, only for it all to unravel, and then back to square one, ponytail and a bobble.

"I recall it coming to a head one day when my P2 teacher Mrs Cairns asked to see Dad after class. Dad was worried all day, thinking ‘what could I have done’? after all, I was only 6 years old at the time and not exactly a disruptive child."

But knowing the difficulties he was facing doing Zoe's hair, the teacher told Mr McBride to "send Zoe to school ten minutes earlier, put a hairbrush and a couple of bobbles in her school bag, and I will do her hair’".

She said it was "a most beautiful moment in time, and highlights what a difference a simple practical gesture can make to a little girl’s day at school".

In his foreword to the book Mr McBride explained how the project came about.

“As much as I would like to claim credit for the title of this book, I’m afraid I owe that honour to my time spent in South Africa, when I came across a book entitled ‘A Brighter Side of Apartheid’," he said.

"That book focused on stories of human kindness and compassion, black on white and white on black.

"It didn’t deny the horrors of the apartheid system, but it went beyond that to find stories where humanity shone through, despite the darkness.

"In our own situation, often it was stories of humanity and acts of human kindness along with our resilient, local sense of humour, that encouraged many to keep going when to give up would have been an easier option."

Mr McBride described working on the book as "a labour of love".

“We got a terrific response when we asked people to tell us their stories that touched them and in some cases changed their lives," he said.

"Some come out of deep personal tragedy, others from chance encounters and spontaneous acts of kindness and concern.

"And some are tinged with great sadness: a group of workmen on their way home stopping to help a woman with a flat tyre. A week later they were murdered at Kingsmill.

"But many are really heart warming: a nine-year-old Michael McConville and friends wandering onto the Shankill Road during the marching season tearfully knocking a door and telling the woman who opened it. ‘We’re Catholics and we’re lost'.

"After biscuits and lemonade she escorted them to ‘home’ territory.

"Michael has never forgotten that act of kindness and compassion."

Mr Larmour added: “It is hopefully a book that will make us all realise that we didn’t get through this dark period in all our lives alone.

"That there beside us were people we didn’t know who could have walked on by, but didn’t.

"I hope as you read these stories you can smile, rather than shed a tear, there have been too many tears.

"I hope you can find comfort in these glimmers of hope where compassion and our local sense of humour shone through at times when finding any brightness wasn’t easy.”

The book is published with the support of the Reconciliation Fund of the Department of Foreign Affairs in Dublin.

Copies will be available from Thursday from the WAVE Trauma Centre.