STAKEKNIFE’S DIRTY WAR: Extracts

In 2022, an emotional McDade told this author his harrowing story: ‘Everybody feared the security team, everybody feared them. Everybody knew, when you’re going to see them, you’re in trouble. You didn’t know if you were coming back, or not; you didn’t know what was in front of you.

‘In 1986, a guy called Eamonn, who was later outed as a tout, picked me up in the New Lodge Road area and drove me down south. We got to a place called Charlestown, in County Roscommon, a small village. I didn’t know the name of the village at the time and only found out a few months later, when I was in Castlereagh [interrogation centre] and Special Branch told me that was where I’d been held. Not only that, they told me exactly where I was, the cottage I was in, the shed I’d been in, where I got beaten for three days – Tuesday, Wednesday and Thursday. I was to be one of the disappeared.’

McDade believed that Eamonn told the British what was happening. On the trip south, ‘we were stopped at a Brit checkpoint, and they got us out. Eamonn went away. Didn’t come back for fifteen minutes. He said the Brits took him away, queried his driving licence. He was obviously telling them where he was going so that they could tail him.’

As soon as he arrived in Charlestown, McDade knew he was in trouble. ‘I just clicked because I saw “Burke and Hare” and John Joe Magee. I don’t know if Scap was there but there was a fat f*****r there, but he wasn’t Scap – I didn’t know who he was. Next thing they put a gun to my head and were, like, come with us. So I got into another car, where they put me down on the back seat and drove away … So, they took me to a farm shed, took me out of the car, stripped me naked, got a clothesline and started tying me up. Tied me up like a turkey, trailed me into the cottage.’

Once they had him inside, ‘they made me lie on a tiled floor the whole time, blindfolded me, put a hood over my head, and started stamping on me … on my head, face and all. They kept standing on me. And they were shouting at me about stuff I knew absolutely nothing about. I knew nothing. I kept telling them. I didn’t know. At this stage, I’m crying. I’m pleading with them. The next thing, bang, scars on my ankles, fag [cigarette] butts.’

Despite having a hood over his head, McDade could see through the cloth that the men torturing him were Burke and Hare. ‘See during the whole thing, it was like a day out to them. Nothing. It was a normal thing to do that. And the wire, the clothes wire they had tied me up with, I was still tied like that for three days, into my arms, into my ankles: excruciating it was.’

There was no break in the interrogation for McDade. ‘Twenty-four-hour interrogation. All night. B*****k naked. I s*** and p****d in the sleeping bag they made me lie in, upside-down. The sleeping bag covered the top half of me upside-down, and it was tied at the bottom.’

This was part of the torture technique in a process that was intended to break McDade. ‘They wanted a result; they wanted somebody thrown out on the street [found shot dead]. They wanted to come back and say, “Hey, listen, we got our tout.” And the sleeping bag was part of the torture ’cause they kept lifting me up in it and dropping me on the floor. That’s why when the kids or grandkids throw their arms around my neck, I freak. It’s the fear.’

It seemed that his interrogators thought that McDade was planning an interview of some kind with a television crew. ‘They kept saying “You’re going in front of a television crew. Just admit these things and you’ll be okay, that’s it. That’s it. It’ll be over and done with. Just admit these things.” I said I wasn’t involved. I knew nothing about them. I knew nothing about the things they were accusing me of. Like, why would I sit in front of a TV crew, and I kept saying this. That’s where it got heaviest again. I kept denying it. The more I kept denying it, the more beatings I got. Beating the f*** out of me. Standing on me. Couldn’t breathe.’

During his entire ordeal, his torturers failed to give McDade so much as a drink of water. At one point Burke ‘got a hot cup of tea and he f*****d that around me’. But despite the horror of what was happening to him, McDade refused to break. When asked if he had ever thought of admitting to what they wanted, he said, ‘Admit to what? I didn’t know what they were talking about.’

It is a testament to Paddy McDade’s integrity and deep sense of right and wrong that he fought off what must have been an overwhelming temptation to end his torture by telling the inquisitors what they wanted to hear. Then, ‘after two days, things started to slow down. Things stopped … Thursday, it started to die off. Somebody had told them they’d got the wrong man. Enough is enough.’

Read More: Stakeknife: British intelligence may have been aware of every IRA operation in Belfast

Scappaticci believed to have died of natural causes and buried in England

*****

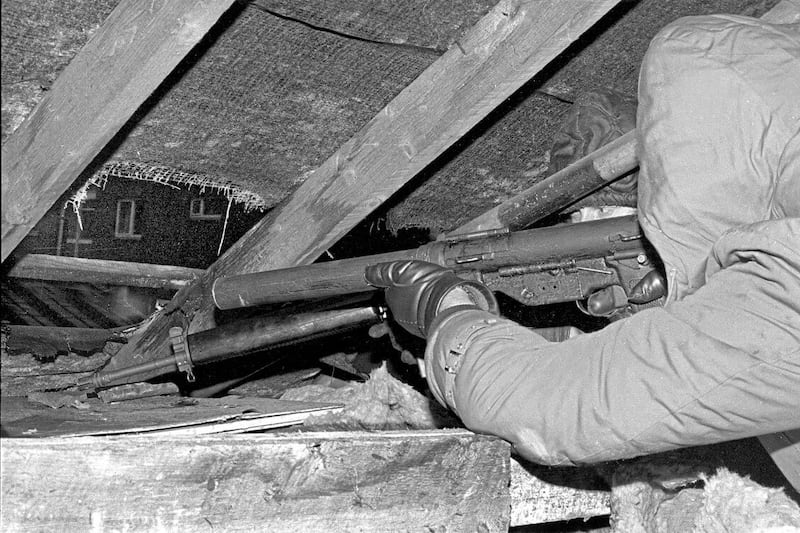

On Friday, 24 February 1989, Joe Fenton was arrested by the IRA, brought to 124 Carrigart Avenue in the Lenadoon area of west Belfast and made to sit facing a wall in a darkened room. The owner of the house, merchant seaman Jimmy Martin, was not arrested for Fenton’s abduction and murder, but he was eventually picked up after police raided his house on 7 January 1990 and freed another Special Branch informer called Sandy Lynch. During his police interviews, Martin admitted that he had ‘lent’ a room to the IRA for their interrogation of Fenton the previous year. Martin named John Joe Magee, Freddie Scappaticci and another person whom he called ‘Eddie’ as the people conducting Fenton’s interrogation.

Martin recalled that, after a rowdy night in the interrogation room, two men, Scappaticci and Eddie, came downstairs at about 10 a.m. on Saturday 25 February and Scappaticci asked for something to drink. Toast was also made and brought upstairs, where Fenton was being held. According to Martin, ‘There was still a bit of noise upstairs. It seemed to be constant. The ceiling was vibrating.’

In a later police interview, Martin spoke of Scappaticci looking out of the downstairs kitchen window as a young lady approached the house. When she entered the kitchen, Martin left the room. The female and Scappaticci then left the house, but not before he popped his head into the living room to tell Martin, ‘We’re away.’

Martin then told police that he heard multiple footsteps coming down the stairs and going out the front door. When asked what happened next, he said that he heard three or four shots. ‘I then heard kids shouting outside the door and I went to the door, and I heard the kid next door saying to her mummy there’s a dead body. I had a fair idea who it was.’

Martin spoke to police of how he later saw the television cameras on the scene and he realised the man in his house had been shot dead. When asked if he tidied up after Fenton and the IRA had left his house, Martin replied that he had taken unused bandages and gloves out of the room, and that Scappaticci had said somebody would come to take what was left away. According to Martin, nobody came.

In another interrogation, Martin identified the female who had come into the house and left with Scappaticci, saying that he had been at her wedding, as had Scappaticci. It is clear from the evidence surrounding the shooting dead of Joe Fenton that Freddie Scappaticci had been in Jimmy Martin’s house, and, according to Martin’s police interviews, was part of the ISU team who grilled the Special Branch agent. At the end of several days of intense interrogation, Jimmy Martin was charged with the murder of Joe Fenton.

It was little wonder that Brendan Hughes was so suspicious of the events surrounding Joe Fenton’s death. What questions might he have asked him had he been given the opportunity? How on earth would you, Joe Fenton, from west Belfast, know the names, the vehicle-registration numbers and the home addresses of police officers? Is your intelligence source from the security services? If so, how, when and where did you meet them? What prompted them to give you this intelligence? Why did you not come to us earlier with these names and addresses? What are you holding back from us? Who is your handler? How is he/she contactable? Fenton’s interrogation may have gone on for days, weeks even, but in the end, he would have been broken. As it turned out, Scappaticci and the ISU succeeded in getting him to admit to being an informer, so it is probable that he would have had a great deal more to tell them had he not been executed due to time constraints.

******

The new unit was known as ‘IS’, or ‘Internal Security’, in IRA circles, although as time went on the press would dub it the ‘Nutting Squad’ because, soon after its formation, the bodies of suspected informers began to be found in back-street alleyways and on remote border roads. Most of the victims had two bullet holes in the back of their heads, the second bullet making sure of the kill. Given its strategic importance, infiltration of the ISU would become a major priority for British Intelligence.

The remit of the new unit was to plug any holes in the organisation’s security by vetting all new recruits, debriefing all volunteers who were being released from police custody, implementing anti-interrogation techniques and getting to the bottom of any operations that had gone awry. This meant that those in the ISU would have known the identities of all new recruits, the nature of the RUC Special Branch’s questions and volunteers’ responses to those questions while in an interrogation centre, and who specifically had been out on an operation that had backfired. In time, Internal Security would have the power of veto over all operations in the Belfast area, which effectively gave them control of the IRA in the city.

Those selected to join the ISU were all seasoned volunteers, men in their thirties and forties who had been in prison and were well versed in the tactics of police interrogators. This would-be corps d’élite were mostly drawn from the Lower Falls’ ‘D’ Company, a unit that had fought pitched battles with the British Army in the early 1970s. The head of the ISU was an ex ‘D’ Company man called John Joe Magee. A portly, middle-aged man with receding, once-ginger hair, Magee, at first glance, looked like an old soak, but he had been a member of the Special Boat Service (SBS), a special-forces unit of the Royal Marines. The former SBS soldier was a soft-spoken, contemplative man but a hard drinker, and yet, inexplicably, he was trusted by the IRA leadership to head up this most influential of departments.

In 1978, Freddie Scappaticci was appointed second-in-command to Magee. This job was tailor-made for the Markets man, because in the ISU his status as a major IRA figure would be enhanced, while at the same time he would avoid having to take part in dangerous operations that could lead to him either returning to prison or being killed. Moreover, he would be exercising life-and-death control over those volunteers unfortunate enough to come to the ISU’s attention. Tellingly, unlike his fellow tout-catchers, Scappaticci was not a heavy drinker, which endeared him to the IRA leadership.

Over the next fifteen years, Scappaticci would prove to be a persuasive inquisitor, often promising those under suspicion of being British stool pigeons that the IRA would set them free if they just gave up the details of their informing activities, but, as Scappaticci remarked, that was a lie ‘and everybody being what they are, everybody has a breaking point, y’know, and they think they’re going home – but they don’t’.1 Whether or not the ISU’s victims had all been informers – and many of the victims’ families dispute this claim – there is a chilling vulgarity about Scappaticci’s remark: the victims did not go home because he, and those he so willingly commanded, made it their business to break them and then oversee their executions.

It was not only the victims’ families who loathed the ISU; there were also IRA volunteers who despised them. ‘Daithi Harkin’, a former Derry Brigade officer, recalled, ‘I got on all right with him [Scappaticci], probably because I didn’t have any great dealings with him. He was IS and I only came across him what … a half a dozen times when dealing with problems in Derry.’

When asked what Scappaticci was like on the occasions that he met him, the volunteer observed, ‘He was fairly professional, to pay him his dues. He would have come up to Derry, done what he had to do, and got out as quickly as possible. But he was a bullshitter.’

The former volunteer went on to explain this contempt for Scappaticci: ‘Y’see, he could talk a good operation, he knew how ops worked, but I don’t think I ran into him too many times out on ops. This guy would be a super soldier now, aye, he would be. Dead bodies behind him all the time. Aye, Scap was good when there was nobody on the other side f***in’ shooting back at him, when some poor f****r was hooded an’ tied up, an’ on his knees in some remote bog, and all he had to do was to put a couple of bullets in the back of the guy’s head.

Extracts taken from STAKEKNIFE’S DIRTY WAR by Richard O’Rawe