THE revelation of Freddie 'Stakeknife' Scappaticci’s death on the same day that Joe Biden landed in Belfast to mark the anniversary of the peace deal is a timely reminder of the murderous and shadowy world he came to symbolise.

Undoubtedly, the unvarnished truth of the man often described as the British government’s most senior agent in the IRA will never be fully known.

Responsible for identifying and executing ‘touts’ in the IRA, as the head of the so-called nutting squad, one theory is that his taste for animal pornography was the bizarre leverage that allowed such a senior figure to be flipped by the security services.

From his public unmasking in 2003 to the investigation and questions that still remain, the Irish News charts the story of one of one of the most controversial figures to emerge from the Troubles.

In keeping with the secretive nature of his life, the west Belfast man (77) was already buried in England where he had allegedly been living under MI5 protection by the time his death was announced on Monday.

Born around 1946 and brought up in the republican Market area of Belfast, Alfredo Scappaticci was the son of an Italian immigrant, Daniel, who ran a chip shop and ice-cream van.

By the age of 16, Nottingham Forest offered him the chance to become a professional footballer but he returned home within weeks.

Working as a bricklayer, he joined the IRA at the start of the Troubles and by 1971 found himself interned in Long Kesh alongside Gerry Adams and other republican leaders.

Released in 1974, he rose through the ranks of the IRA before being arrested for VAT fraud.

How and when the security services recruited him is unclear, but the theories include a reprieve from VAT charges, that he approached the security services after republicans beat him up for having an affair with an IRA member’s wife and that he became a drinking buddy with a young army officer.

In 2018, he was convicted in London of two counts of possessing extreme pornography which included images of animals but it is unknown if this perversion had been used against him by his handlers in the past.

Read more:Prosecutors continue to consider Stakeknife files for other suspects

What remains clear is that by the early 1980s he was in the pay of the notorious military intelligence outfit, the Force Research Unit (FRU).

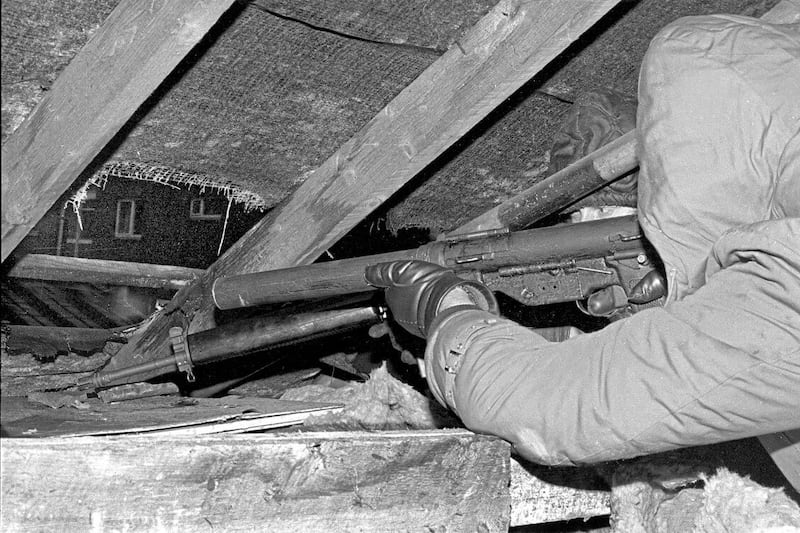

At the time, republicans wary of infiltration and informers had set up the IRA’s internal security unit or nutting squad.

As the head of the unit, Scappaticci routinely tortured suspects in safehouses for days at a time in return for confessions.

With the victims stripped, beaten, blindfolded and hung upside down, he is reported to have once said: “Everybody has a breaking point and thinks they’re going home. But they don’t.”

Security sources have attempted to defend their use of their “golden egg,” with information from Scappaticci said to have saved lives by stopping major IRA operations including an IRA attack on the British army in Gibraltar.

Questions remain, however, on allegations his handlers knowingly sacrificed lives in order to protect their source in the IRA.

This included turning a blind eye to warnings that informers would be executed, and suspicions that a bogus tip-off to loyalist paramilitaries led to the killing of the innocent pensioner Francisco Notarantonio instead of Scappaticci.

After successfully leading a double life through the 1980s, Scappaticci finally ran out of road in January 1990.

In a west Belfast safehouse, he had been among those interrogating the informer Sandy Lynch.

Unknown to him, the house was bugged and the police raided the house when Sinn Féin’s publicity Danny Morrison arrived at the property.

Police who did not realise Scappaticci was a spy found a fingerprint in the house which caused him to flee to Dublin.

It’s reported that his FRU handlers came up with an alibi, meaning he was released after being arrested in Belfast in 1992.

Morrison was jailed after the incident but his conviction was eventually quashed, while Scappaticci was quietly retired from the nutting squad.

By 1999, the army intelligence officer Ian Hurst informed The Sunday Times of Stakeknife’s existence before revealing his full identity in May, 2003.

What followed was a media frenzy after four papers in the UK and Ireland revealed Stakeknife’s identity to the public.

The Sunday Herald in Glasgow had contacted the Ministry of Defence in advance, and were told it would probably be safe to publish if he was already named in another jurisdiction.

Three Irish titles - the Sunday Tribune, the Sunday World and the Sunday People – were also ready to name him.

Paddy Murray, editor of the Sunday Tribune, said the paper had originally planned to wait another week before it became clear the cat was out of the bag.

"Our view ethically is what we were doing was exposing a wrongdoer, but ethically it made it easier that he wasn't at risk,” he said at the time.

"It's an enormous scandal and an enormous story - I do hope it runs and runs. Something has to come of it, because this should really be the end."

The Sunday People reporter Greg Harkin also took much of the credit for his work in revealing the story.

Within days, Scappaticci emerged from hiding in the offices of his solicitor in west Belfast.

In a filmed interview, he denied the allegations and criticised the newspapers for failing to contact him for a response.

When asked if he had been in the IRA, he would only say he had been in the republican movement but had not been involved for 13 years.

His lawyer claimed his client had only left his home because of the “media onslaught” on his character.

In a separate news conference, Sinn Féin’s Gerry Kelly said: “I have no reason to want to speak to Mr Scappaticci and I don’t think republicans will want to do it either.”

Instead, he criticised “faceless and nameless securocrats” in British intelligence for making unsubstantiated allegations against Scappaticci.

It was reported that after travelling to England, Scappaticci initially turned down an offer of MI5 protection and quickly returned to Belfast for a meeting with the IRA leadership.

It’s suspected that a deal was made, and the dual press conferences were an attempt to play down the story and reputational damage caused to the republican movement.

Whatever the truth behind closed doors, Scappaticci was allowed to live out his days unlike over 40 victims he was alleged to have tortured and kidnapped before sentencing them to death.

After denying the charges during his surprise interview, Scappaticci would go on to take legal action against the British government in an effort to restore his reputation.

Joining a witness protection scheme in England, he left behind his wife Sheila and mother of what was thought to be his six children who died in 2019.

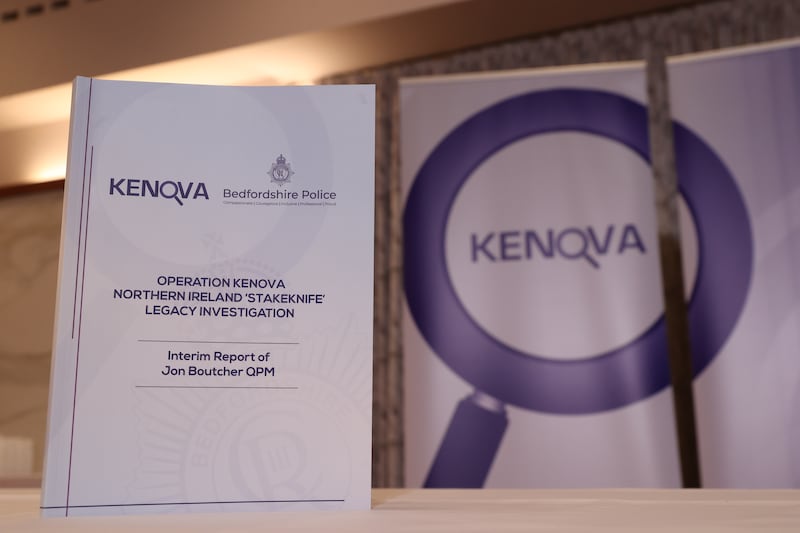

A major investigation was launched in 2016, Operation Kenova, which sought to determine if Scappaticci, the British government, the army and the security services committed any crimes.

Led by the former Bedfordshire chief constable, Jon Boutcher, the probe has cost £30m so far and has involved 50 detectives.

Reacting to Scappaticci’s death, Mr Boutcher said he would consider the implications for the investigation and publish an interim report this year.

The investigation had led to Scappaticci's 2018 conviction for extreme pornography, where he received a suspended jail sentence.

Speaking in Westminster magistrates at the time, Chief magistrate Emma Arbuthnot told him: “I can see you are not a well man at all – you have very serious health issues – and that you live a lonely life.”

This week, Mr Boutcher said he was still committed to providing truth for families.

He added that people could now feel more open to speaking to the Kenova team about Scappaticci, who had long been “accused by many of being involved in the kidnap, murder and torture of potential PIRA informants” during the Troubles.

Kevin Winters, a lawyer representing relatives of those killed by the Provisional IRA, said the news of Scappaticci's death was frustrating for families who have already waited six years for Mr Boutcher’s report.

He said the death could influence the content of the report and the possibility of criminal prosecutions and that families were already suspicious of how authorities appeared to keep Scappaticci’s burial quiet over Easter weekend.