In a new book about Irish actor and hellraiser Richard Harris author Joe Jackson claims the film star was threatened by both loyalists, who believed he was sympathetic to the IRA and republicans over his bid to curb fundraising for the organisation in the US. In the edited extracts below Mr Harris describes himself as a republican and voices support for a united Ireland but said he could not condone violence.

On July 21st, 1982, Richard gave a Press Conference in London to announce that the touring production of Camelot would open at the Apollo Theatre in the West End the following November. It was to be directed by Michael Rudman.

A snippet in a showbiz column reported that ‘Harris entertained the Press with a torrent of reminiscences about his New York performance in the musical. And, more personally, about his reasons for now being teetotal.’

But there was one contentious subject no one dared to ask Harris about until that uncredited journalist did. A day earlier, during British military ceremonies in Hyde Park and Regent’s Park, the IRA detonated two bombs, killing four soldiers of the Blues and Royals at Hyde Park and seven members of the Royal Green Jackets and their horses in Regent’s Park.

‘But what about the views of one of the world’s most famous Irish men on the London bombings, which killed a number of people twenty-four hours before?

Nobody saw fit to ask him—although Harris once wrote a poignant and devastating indictment on the Irish problem called Too Many Saviours on my Cross. Warily, I put the question. For once, words escaped him. All he could mutter was, “dreadful, just dreadful,” but his tears said it all.’

Harris’s tears didn’t say it all. And those few words were not all he would say about the IRA’s bombing campaign. Also, this was not all the British media would say about Richard Harris in relation to the IRA.

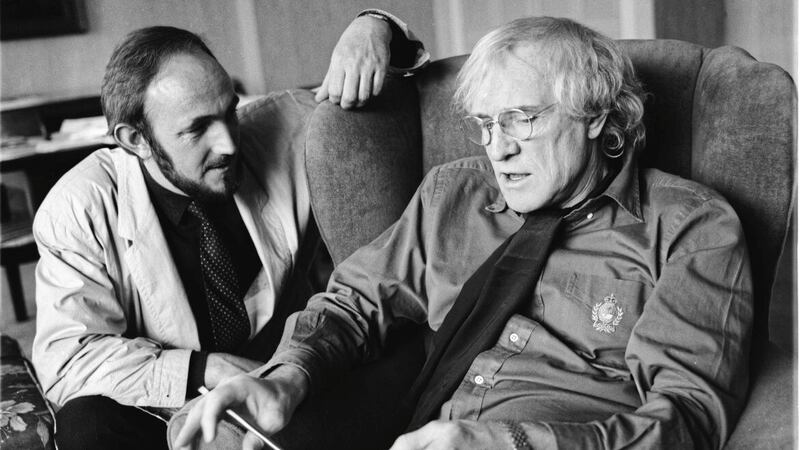

Far from it. Indeed, that snippet was more ominous than many readers probably realised. A month later, during an extensive interview with Tom McGuirk, for the Irish newspaper, the Sunday Tribune, he and Harris had extensive discussions about the IRA.

But in that published article, the IRA was not mentioned. I mention this here only because Richard Harris and Tom McGuirk would end up at war in court within a year. Four years later, during our first interview I asked Harris about his alleged support for the IRA.

J: Rumours about your support for the IRA probably go back to the early 1970s, when you attended a fundraising function for Noraid in New York. Did those rumours ill-effect the London run of Camelot and lead to you receiving death threats at the same time?

R: Rumours do go back to those days. They did damage that run of Camelot, and yes, I received many death threats [from Loyalist paramilitary organisations in Northern Ireland]. A journalist on the Sunday Express, John Junor [Editor-in-Chief 1954-1986], wrote a piece after I did the Royal Variety command performance, at which I met the Queen Mother and shook her hand.

The following Sunday, he said, ‘I hope the queen mum wore gloves shaking the (blood-stained) hand of Richard Harris. He described me as a killer, financing IRA death squads, and so on. We then had bomb threats at every performance, bombs arrived at the theatre, and I got 17 death threats by phone and 11 by letter.

J: How much truth was there to the rumour of your support for the IRA?

R: I was a tremendous supporter of Noraid. I raised a fortune for them in America, understanding that the money raised was to go to both Catholics and Protestants and rehouse the wives and children of people who were in jail. This is what we were told.

But the article in the Sunday Express was misleading because they singled me out and didn’t mention who else was at that table during that Northern Aid function. It was a non-sectarian, nondenominational event to raise funds for all. The IRA was not mentioned that night by any speaker. It was recorded, and the tapes were investigated by the American Department of Justice, who were afraid it might be a subversive event. They decided it wasn’t. We had at our table alone a Protestant Bishop from Northern Ireland, many Protestants and Catholics, and Jewish senators. But in many newspaper reports, it was said to be an IRA/Sinn Fein table. It was not.

J: But you support the Irish republican cause, don’t you?

R: I am a republican. I believe in a united Ireland. I also believe that violence was forced upon the Irish. Go back to the history of the old Provisional IRA, and you see that this is true.

There is no question that violence perpetrated by the Brits led to the creation of the provisional IRA. They are the result of British tyranny and British violence. But I do not approve, and I cannot approve, of the IRA taking the battle into the private sector. I cannot approve of them blowing up, for example, Harrods. I just can’t. Though one wants to achieve a United Ireland—if that’s what everybody wants, and whether they do or don’t, I want it, and those who don’t will have to accept it when it comes—but I cannot condone violence.

J: You just said you do, to a point.

R: But not in the private sector. There is a war between the IRA and the British Army, and that is the territory. People will die. But taking it beyond that, I cannot believe in, and I will not condone, and I do not support.

(Here, I must break away from the chronology thus far in this chapter, if only to try undo the lie still prevalent, particularly in the UK, that Harris was a lifelong supporter of the IRA)

Within six months of this interview, unknown to me, Richard gave lectures to Irish societies in America and discouraged them from donating money to the IRA or arms.

This led to him receiving death threats from the IRA. Six months later, during a libel case in London, Harris mentioned those death threats and said, “someone has to take a stand against the IRA. The killing must stop. I have had six death threats on my life this year, and they will start again because of what I am saying in this court.” None of this was reported in the British media.

Nor was the fact that on March 17th, 1989, before a concert Richard gave with the Chieftains in Carnegie Hall and a pre-gig television show they did at the Tavern on the Green in New York, he received more death threats from the IRA.

They said no such threats were made. But the NYPD took the threats seriously enough to have bomb squads at each event. And during the event at the Tavern, Richard, in a broadcast beamed back to Ireland, recited There Are Too Many Saviours in my Cross, his 1972 plea to “both sides” for reconciliation.

Cliff Goodwin, in his book, Behaving Badly, claims that as far back as 1970, Harris’s name appeared on a Northern Ireland Intelligence Report, which was sent to the Metropolitan Police Special Branch in London.

It claimed that a hard-line Loyalist group had put his name on a list of high profile Irish people it intended to kill.

One of its London based ‘cells’ planned to shoot him one night as he came home to Tower House. But the gang ‘received a high-level tip-off from Belfast’ and was that the attack had been ‘aborted for political reasons.’ Goodwin further claims that nobody thought it necessary to warn Richard Harris.

This may be true. But a story Harris told me in 2001 suggests the Criminal Investigation Department in London wasn’t pushed when it came to protecting him in 1983.

“When we were doing Camelot here in London, my life had been threatened so much because of that republican thing that the Criminal Defence Department of the police here came to me and said, ‘look, we may not like you, but you are a guest in our country, and we have to protect you as a guest.’ So, they had a guy, all day, watching me.

Finally, I said, ‘I don’t want to put the English taxpayer to this expense. If I get a bodyguard, will you give him a licence to carry a gun?’ They said, ‘let’s see who he is.’ So, I introduced them to this guy who had been protecting me anyway, and they said, OK’ and gave him that licence. He lived in the room opposite, here at the Savoy, with a gun and took me to the theatre etc.”

“Keeping a safe distance, I presume.”

“Yeah, he was never obtrusive. Going back to the days of the Kray twins, I’ve got great contacts with the underworld here, still. He was one of them.”

This subject arose after I asked Richard if it was true, as Tom McGuirk told me, that he sent over to Ireland a “heavy” to get back biography tapes. Harris continued that part of the story.

“Yes, when this thing happened with McGuirk, I sent him over. He’d have shot him. I said, ‘don’t shoot him, just get back the tapes.’”

“Tom told me his side of the story and said he didn’t hand over the tapes that night.”

“No. But we got them back.”

“Tom is a tough cookie and has “friends!”

“Yeah, but we took him to court, and the judge ordered him to give them back. We did it civilised, first, and he may be a tough cookie, but he wouldn’t have handled that guy.”

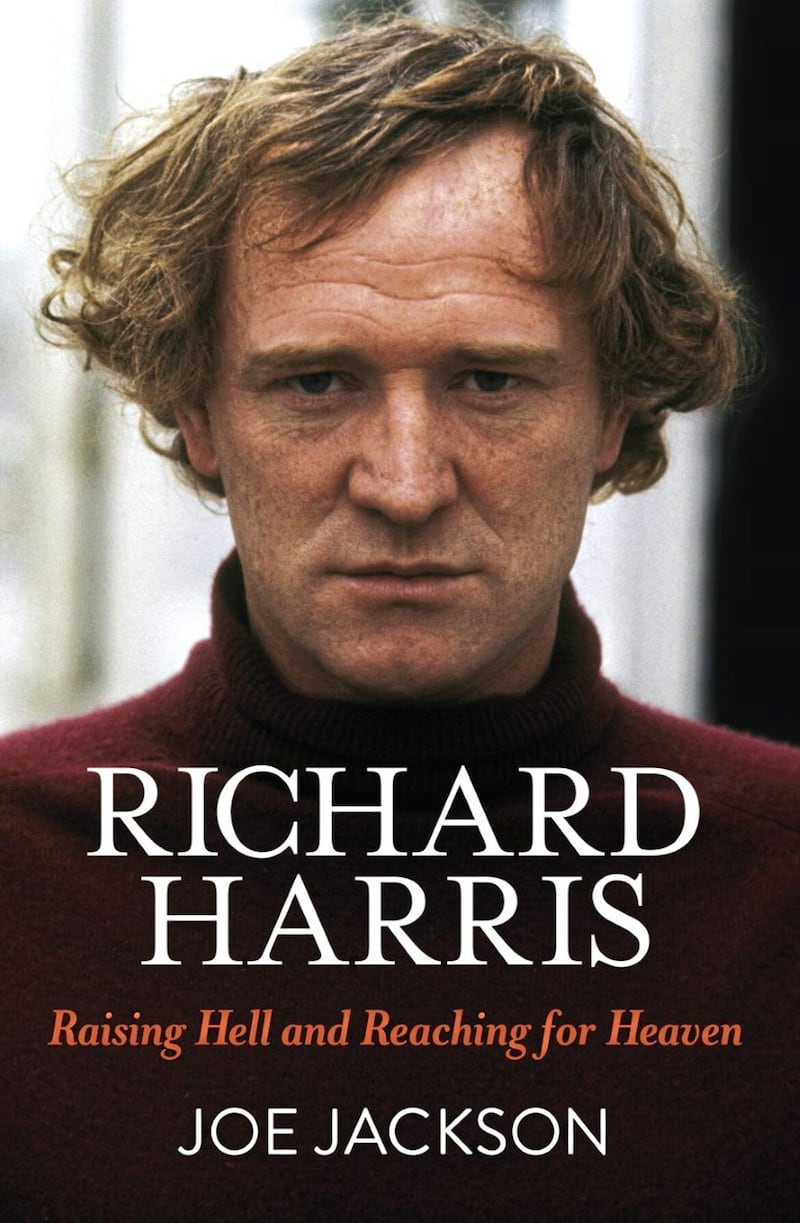

:: This is an edited section from a chapter in Joe Jackson’s book 'Richard Harris Raising Hell and Reaching for Heaven'.