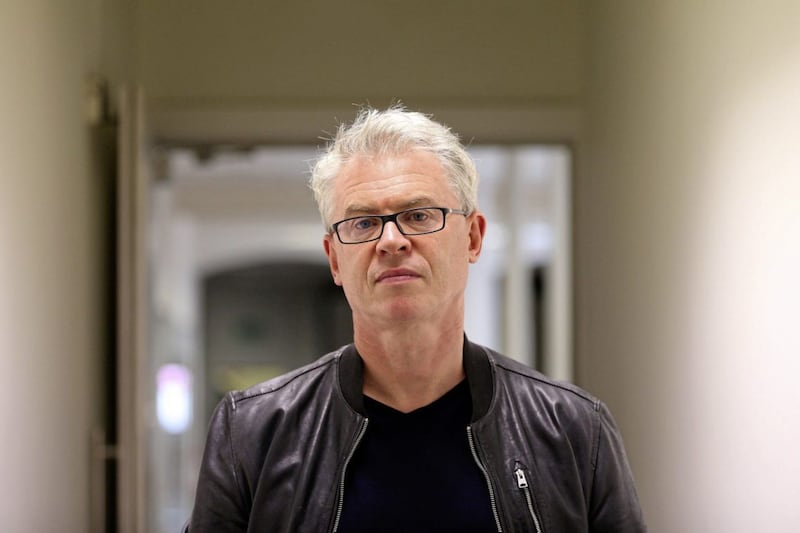

THERE'S Public Joe. We know Public Joe.

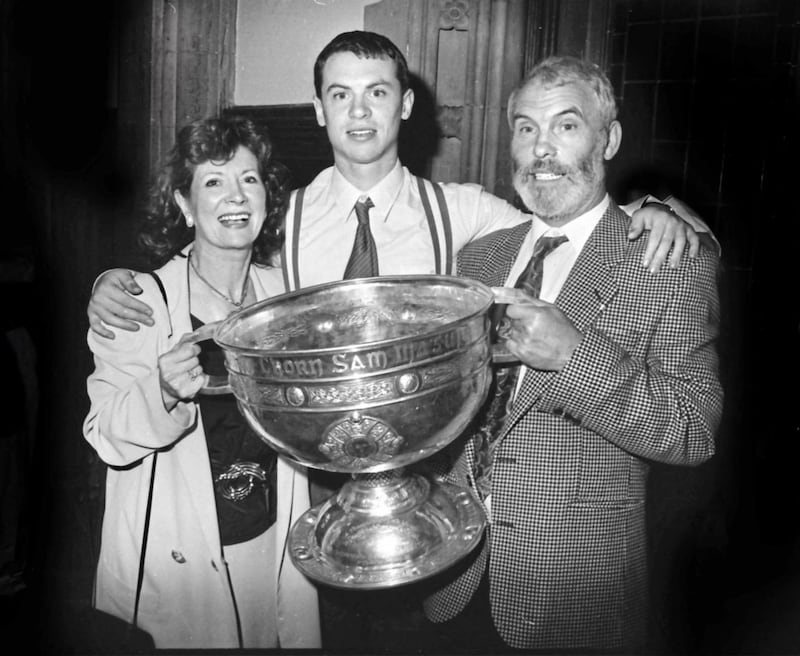

Joe the Footballer. What a footballer. One All-Ireland, two All Stars. Kisses for the crowd.

There's Joe the Pundit. Passion, mischief, humour. The Sunday Game, Sean Cavanagh. The exit from RTÉ.

Joe the Barrister. Joe the Columnist. Joe the Good Samaritan, who took in a homeless man for a year. Plenty of Public Joe.

But there's Private Joe too.

Private Joe doesn't sleep much, never has. Maybe a couple of hours a night.

For years he would see a boy at the end of the bed. Badly-burned, a terrifying sight. Gone now, but fear can still take hold at night.

There was childhood trauma. He's hinted before, confirms it now.

And from confronting that, a new Joe.

"I would say my education as a human being came very late. Genuinely, I mean that.

"You had this parallel thing where you had the reality of your life, your private life, which was a life of fear and shame and violence.

"And then you had this other life, where I was flying at school, I was playing basketball for Ireland, I was no sooner out of school and we were All-Ireland champions. I was a barrister, people were lauding me, and I was earning money that my parents wouldn't have dreamed of. And on telly being lionised, and the whole country was talking about you.

"And so you had this private Joe and public Joe. And people would have been amazed to think that these things were going on beneath the surface. Constantly going on beneath the surface.

"So since the kidney especially I have been having a terrific late education in getting to grips with life, and just accepting my own very small place in it, and improving my relations with everybody."

It didn't start with the kidney, but it's a good place to start.

The story has been well told. Joe barely knew Shane Finnegan at the time. They were taking the under-10s at St Brigid's GAC in south Belfast when he discovered Shane desperately needed a kidney transplant.

"I'll give you a kidney," he said.

The surgery was done in London, two men lying side-by-side in hospital, life flowing from one to the other.

Later would come the devastating news that the kidney was rejected. But the euphoria of that selfless act had already changed Joe. A profound change that brought him "deeper into life".

With Shane and others, he embarked on a campaign to raise awareness of organ donation.

A decade on, the results have been nothing short of spectacular.

Around 500 sports teams now wear the 'Opt for Life' logo on their jerseys. Infrastructure has improved, outcomes too. Northern Ireland has shot up the global league table for live donors.

But when the surgeons in Guy's Hospital opened Joe up that day in 2012, it opened up other wounds as well.

"That opened me up to the past.

"I thought I was fine and I was bomb-proof, and everything was fine, but in fact it opened me up to the past and, you know, I'd say I probably had close to a serious emotional breakdown in private. I would have found myself crying in the shower for no reason.

"And then sort of the realisation of the kidney was that maybe partly it was to atone for the terrible crimes committed by people close to me.

"To somehow say look... I wasn't part of this, and this is my act of atonement."

He adds: "I was surrounded by violence. I suffered it myself. There was no-one to turn to. In those days, what could you do?"

Joe doesn't elaborate, but says he was relieved and excited when he left Dungiven to be a boarder at St Patrick's College, Armagh.

"Looking back, I think a part of me giving the kidney was me taking my place as an adult and saying look, I'm as good as anybody else.

"... You are opened up and very emotional and very sensitive to the world around me then, and the past came flooding in, things that I barely remembered."

For two years, each Friday at 6am, he would go to see someone, describing it as the "weirdest experience".

"And I could be sitting in the car afterwards for an hour, overwhelmed with emotion and devastated, and then you have to pull yourself together and go into court. 'Is this trial ready to proceed, Mr Brolly?' 'Yes, my Lord, it is.' 'Call the first witness.'

"And then you're back to that duality of, well, you have to get on with your life - everybody's got problems, you know, so it was a fascinating experience going through all of that."

The result has been a Joe more at peace with himself and his place in the world.

"I don't see myself as a big deal any more... I don't see myself as anything like that.

"I love taking the underage teams at the club, and I enjoy my friends, and I'm better able to take my place and relax and not try to perform all of the time."

The oldest of five children, Padraig Joseph Brolly had come from a family of performers.

An uncle of his mother, Bill 'Shawn' Corey, left Tyrone for Hollywood and became a dance double alongside Fred Astaire, Gene Kelly and Rita Hayworth.

His parents, Francie and Anne, were both prominent folk singers before being better known as Sinn Féin politicians - Francie an MLA at Stormont, Coalisland-born Anne the first female mayor of Limavady council. They would later leave the party over abortion and join the pro-life Aontú.

:: Part two: Joe Brolly on the DUP, a united Ireland and his friendship with US President Joe Biden

In Armagh, Joe sang soprano in the cathedral choir and played the lead role of Curly in a school production of Oklahoma! He is also an accomplished pianist.

He studied law at Trinity College Dublin and was a contemporary of Arlene Foster at Queen's before "stumbling into" a career in the courts in Belfast.

As a defence barrister he is an actor in real-life dramas. But his true skill is the art of persuasion, convincing a judge or jury of the inescapable logic of his argument.

He identifies with the underdog and enjoys outwitting a system he sees as stacked against the accused and perpetuating an unequal society.

Recently he has taken on work in the Stardust inquest, as families still seek answers about the deaths of 48 young people in a fire in Artane in north Dublin on Valentine's Day 1981.

Joe's own student days in Dublin had opened his eyes to a world beyond the narrow certainties of life in Dungiven during the darkest years of the Troubles.

Born in 1969, he was still a young child when his father was interned for almost three years.

The conflict was inescapable - the bombs, the bullets, the house raids. Far from normal, but somehow normalised.

Who was the badly-burned child he saw? Was it him? Was it from a bombing, like the nearby village of Claudy where three car bombs killed nine people in 1972?

Joe was only three at the time, but in 2005 his father was arrested in relation to the atrocity. He strongly denied any knowledge of it and was released without charge.

"I don't know. It was just a badly-burned child," Joe says.

It was certainly a disrupted childhood and he has spoken in recent years of no longer having any relationship with his parents.

Was he reconciled with his father before his death last year? He mentions the Troubles and says he "died a stranger to me really".

One thing he did learn from his father, though, was the importance of community.

"I was always a community person, because my father was always a community person. And I would have always done anyone a turn regardless of who they were or what it was.

"But after I gave the kidney then it was a whole new thing. I saw the real power of it, and the transformational impact, not just for a person, but in a community, where you genuinely think about other people, and you're genuinely interested in other people doing well.

"It takes the cruelty out of it, you're able to rise above it, you know, and people start to get each other, and that's where community starts."

That communitarian spirit courses through the GAA, where the organ donation message spread like wildfire.

When he gave his kidney to Shane Finnegan he didn't know him personally - but the fact he was a GAA man was enough.

"Because the building block of society is 'I know you, and you know me'.

"And so whenever I did that it had such an explosive effect in the GAA community, because everybody knows you - they don't actually know you, but you know them and they know you.

"I can go into any club in the north or they can ring me and say it's Joe Brolly, or it's X from Crosserlough, or it's X from Ballybofey GAA club, or St Eunan's or whatever, and we know each other.

"And so whenever that happened, everybody felt it a part of their own experience. I'm a GAA person as well, I have a GAA family. I can see how this would make a big difference in my life as well."

The GAA is "the glue of Irish society", and what stops us becoming just another nation of consumers.

"I think there is such huge discontent in England and such problems there because they have lost their sense of community.

"They were ravaged in the world wars, and they are now being taken over by a very dangerous sort of right wing politic."

He shifts forward, more agitated.

:: Part two: Joe Brolly on the DUP, a united Ireland and his friendship with US President Joe Biden

"I think that Brexit was a really dishonest project and it was sold on the basis of emotion... Go for their emotions, stir them up, make them angry: 'f*****g black people, f*****g Asians, look at those f*****s, they're taking our jobs, look at that, and the French are f*****g laughing at us'.

"And you go into any of the wee working man's clubs - we've seen the vox pops on Channel 4 News or BBC. 'What do you think?' 'Fair play to Boris, he showed them, he showed the Germans.' These mythical enemies that are not real at all.

"And we see this in England - and the great discontent there is in that society - because of the absence of community."

Is this marshalling of community spirit in the cause of organ donation what he is most proud of?

"I wouldn't say I'm proudest of it, I'm delighted. A better way to put it is I'm delighted there are so many people alive now who would be dead otherwise.

"I mean I have visited children who were at death's door and then they've got an organ and now they're playing with the dog in the back garden and they're going out to their training. I have had so many experiences like that.

"I've gone to games with people who have had transplants, who would have been dead otherwise. We've socialised together. I go to gatherings, two or three times a year, where we spend time together.

"The dead are living amongst us because of organ donation. I wouldn't say I'm proud of it, I would say I'm delighted by it. And people have taken it up themselves. Clubs do things all the time around Opt for Life, counties do Opt for Life. It's become part of the national psyche now which is terrific."

So what now for Joe Brolly? Aged 52, which Joe will we see next?

It's unlikely to be on RTÉ. After 20 years in the nation's living rooms, he was abruptly ditched from its GAA coverage in the week between the All-Ireland football final and replay two years ago.

The catalyst may have been criticism of a referee, later retracted. But the ground had been shrinking under him for some time, as he rebelled against more scripted and stats-based analysis.

Joe maintains that the broadcaster is making a big mistake.

"I have to say I was a bit shocked by that, but you know, that's life. I think that the bottom line was some human beings are allergic to other human beings and the head of sport pretty clearly was allergic to me. And that was it."

If doors at RTÉ have closed, other public platforms remain. He now provides his brand of TV punditry for eir Sport, as well as writing about sport and politics in columns for the Sunday Independent and others.

The coming months will hopefully also see the culmination of almost a decade's work when Stormont legislates for a system of 'opt out' organ donation, due to be debated at the assembly today.

What we are left with, then, is perhaps Joe the Evangelist, the man behind the sometimes abrasive exterior who now travels from town to town spreading a gospel of community, empathy and altruism.

"I always really liked the New Testament. Greater love hath no man than to lay down his life for his friend, all that sort of stuff.

"And it was always preached to us since we were small, in school and Mass and at home, selflessness, empathy, put others before yourself.

"And it was amazing to me that people weren't doing it, because the greatest kick you can get is through selflessness. I mean that sincerely. I learned that."

:: Part two: Joe Brolly on the DUP, a united Ireland and his friendship with US President Joe Biden