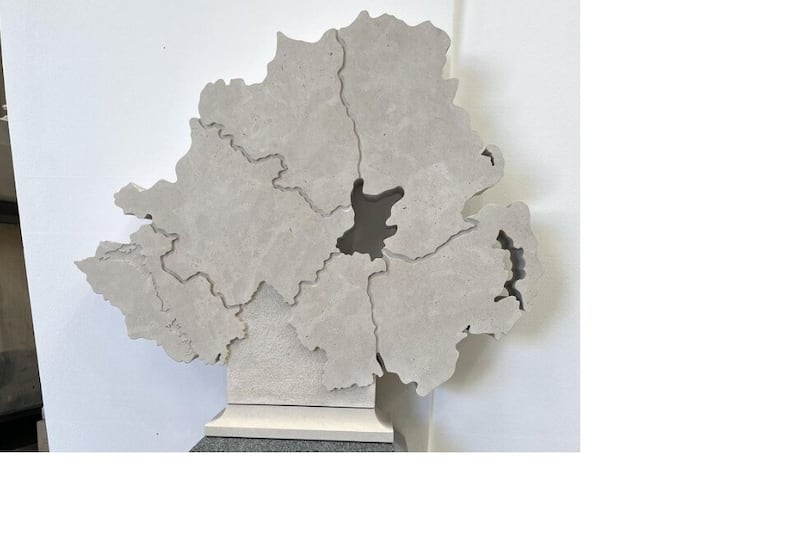

A century, one hundred, a time to celebrate?

Or to reflect on the failure to change, to move on from divisive politics, and the lack of separation of church and state.

I have to say that I am tired of the green and orange glasses tainting all of our political thinking. From an early age we are pickled in divisive language and thinking that infects us for life. It is worse than a virus, as there is no vaccine.

My first recollection of there being a them and us was when I was in the garden of 137 Stockman’s Lane on a Sunday afternoon, before the M1 was built, at the age of four.

I heard a loud cheer, a celebration, and asked my Mum: “What was that noise?”

“That’s the rowdy football. They play on a Sunday. We don’t.”

They, them, us, what was going on? Why didn’t we play on Sunday? What had I done to deserve the long Sundays of being Protestant?

Then we moved, to Adelaide Park. Middle-class Malone Road was idyllic. I became friends with Michael and we played football and cricket, ran the neighbours ragged throwing stones at doors and getting into serious hot water for ripping out the remains of the daffodils from a garden to use as weapons.

Michael went to chapel, I went to church; he had priest at Mass, I had a minister at a service. His house had statues, we hadn’t.

But every afternoon until we were 11, we threw our schoolbags down and headed over to the Aquinas Hall tennis courts (it used to be on the Malone Road) and joined the gathered throng of kids for football.

There were nuns floating about, who taught in the school, and lived in the house beside us. But most of all there was football. Michael in his Celtic shirt, me United red. We watched the 1967 European Cup final and were overjoyed at the Hoops winning.

The area was totally mixed, medics and businesspeople and public sector families from both communities and Malaysian students down the road that played table tennis with us. Mums at home, Dads at work.

But all the while I was being educated in the ways of Northern Ireland.

Catholic neighbours were Fenians when not in hearing reach, and I don’t think totally pejoratively, but certainly hierarchically. We were ‘better’. They worked in bars. Jokes were racist and sectarian before we knew those words. I can still shame myself remembering some.

To this day my Mum, at the mention of our neighbours, says “They are nice people”, retaining to her 88th year wonder that people from a Catholic background were, well, just the same as us.

And Michael and I remained friends until 1969, when we both went to big school, the Troubles erupted, and we have never spoken since, walking on opposite sides of the road, both literally and in our tribal uniforms, me Inst, him St Malachy’s.

I was infected. We had one Catholic in our year, out of 180 boys. We holidayed in a caravan in Cloughey, where there were two bands, one pipe, one flute, and a bonfire for us all to swarm around on the eleventh night. It was fun, with no political awareness.

The Lambeg drum was marched at 3am to the small enclave at the end of the road where Watsons had their shop. The Watsons were Catholic.

Meanwhile, during term, it was off to school. Belfast city centre, from 1969-76. The peak of the bombing, a learning curve of where to go and to avoid, the regular bomb scares initially getting us sent home but then being told to search our bags for anything suspicious.

Lots of black schoolboy humour. Lots of UWC blackouts. Lots of violence and propaganda.

I was on a side. I was saturated with unionism, and an education that was British. I was also by now a non-Prod Prod, having fought the bit out with Dad that it couldn’t be right that two sets of Christians were slaughtering each other. I stopped going to church except on Christmas Day.

I had also started thinking, reading and spending most of my time with Martin, whose family environment was about as liberal as you could get in Northern Ireland. Debates, discussions, cigarettes, beer, motor bikes and girls, and friends across Derryvolgie Avenue from Catholic families, hanging out, avoiding any politics.

I went to Queen’s. History and Politics, but more than that; much more than that, an involvement in Rag and Fringe Festival. People from all parts of NI. From all parts of Belfast.

My girlfriend from a family of 11 in Derrygonnelly, who magically transformed from a number into people as soon as we met.

A conversation overheard with Kieran and Michael casually talking about a night that Michael had been beaten by the RUC. Not to make a point, just part of a story that continued for another reason. What? That didn’t happen. They laughed. No it didn’t, on the Malone Road.

I moved left, and further left. I was elected to the Student Council. Alex Attwood and Jim Wells were young pups. It was great craic, and life changing. Not to be fixed in a new opinion, but to think about what I thought.

There was friction at home. How could I have become a left-wing republican? Dad was troubled, and only now as a parent do I realise that it was hard for him. That the education he so wanted me to have resulted in me becoming distant.

He was angry, he was frustrated, he had left school at 14 and had so wanted to be educated, and here was me, being too smart.

I challenged and debated, raised hackles at dinner parties and in pubs by being dogmatic about getting people to stop being so dogmatic. I worked with Dad and we became friends, as he realised that I could think, and so maybe it wasn’t all bad.

I thought about people, about creating advertising campaigns, and about how we were all worse off for being trapped in our early learning.

So I have drifted back to the middle class. But still see that after 100 years we all see everything through green or orange lenses.

If we want to move forward, we need to leave that behind, all of us, all of it, on both parts of the island.

We need to spend 10 years focused on prosperity, on growing our markets on the island by building relationships that don’t depend on where the government is located, but is about building the economy, the health provision, jobs and demolishing the sectarian division that has tainted the 100 years of Northern Ireland.

We need to remove religion from education and politics and put it back in the home, for personal choice, not legislation.

All in all we need to grow up. To get past the childishness of thinking that both unionism and nationalism need to survive.

To go past knowing how every politician is going to answer every question because they are programmed and like software can only give one solution.

100 is old enough to start trying to grow up.