AN RIC district inspector suspected of taking part in the murder of a Cork republican 100 years ago is thought to have been killed hundreds of miles away in Co Antrim with the victim's personal gun.

Co Monaghan native Oswald Swanzy was shot dead by the IRA as he walked through Lisburn on Sunday August 22 1920.

His killing sparked a series of sectarian reprisals that resulted in Catholic homes and businesses in the area being attacked in an event that became known as the 'The Burnings'.

The violence resulted in at least one death and hundreds of people being forced to flee the mainly unionist town.

The RIC officer had been tracked down by republicans on the orders of Michael Collins after he was implicated in the shooting of Tomás Mac Curtain.

The Sinn Féin mayor of Cork, who was also in charge of the IRA's Cork No 1 Brigade, was gunned down in his home in March 1920.

The killing, which was carried out by members of the Royal Irish Constabulary with blackened faces in the dead of night, caused outrage across Ireland.

It came at the height of the Black and Tan War, also known as the War of Independence, in the years following the 1916 Rising.

At an inquest it was found that Mr Mac Curtain had been “wilfully murdered” and that the killing was “organised and carried out” by the RIC and “officially directed by the British government”.

Several people were named including RIC District Inspector Oswald Swanzy and British Prime Minister Lloyd George.

After the killing Mr Swanzy was transferred from Cork to Lisburn, a mainly unionist area which would have been considered relatively safe.

However, on the morning of August 22, an IRA unit comprising members from Belfast and Cork shot him dead near the town's cathedral.

It was reported that the RIC man was returning from church, although it has also been suggested he may have been making his way from a local pub.

This was the second time the IRA had tried to kill DI Swanzy after a failed attempt in Downpatrick, where he had been temporarily posted, months earlier.

It was said that one of the guns used in the attack was Tomas Mac Curtain's personal weapon - leaving little doubt as to why he was targeted.

It later emerged that Swanzy himself had signed the permit for the gun in the mistaken belief it was for a Cork-based loyalist.

Within hours of his killing, unionist mobs sought revenge on the Catholic population of Lisburn and outlying areas.

Dozens of Catholic-owned bars and businesses were left smouldering shells during the violence, which spread in the days after the attack.

Only one bar in the whole town escaped the looting and arson.

Homes were also targeted as many Catholic families fled.

Nuns based at the Sacred Heart of Mary Convent in the town were advised by a British army to abandon the building as it became increasingly impossible to guarantee their safety.

The town's parochial house was also singled out and gutted in a blaze that also destroyed valuable parish records.

It was reported that some of those present danced around in priest's vestments and local folklore has it that some rioters toyed with the idea of digging up the remains of a Catholic priest who had been buried weeks earlier.

The walls of the building were later covered in graffiti which included 'No Pope or prists (sic) here' and 'to hell with the Pope'.

Much of the violence was said to have gone largely unimpeded by the RIC and British army.

Some of those who fled the town and later returned were forced to sign a declaration saying they had no sympathy with Sinn Féin and pledging loyalty to “king and country” before being allowed to return to work.

There were also reports of armed men setting up road blocks.

An RIC report later said that after three days and nights of rioting, 1,000 Catholics had to flee the town and damage was estimated to be in excess of £810,000.

Some of the families who left never returned.

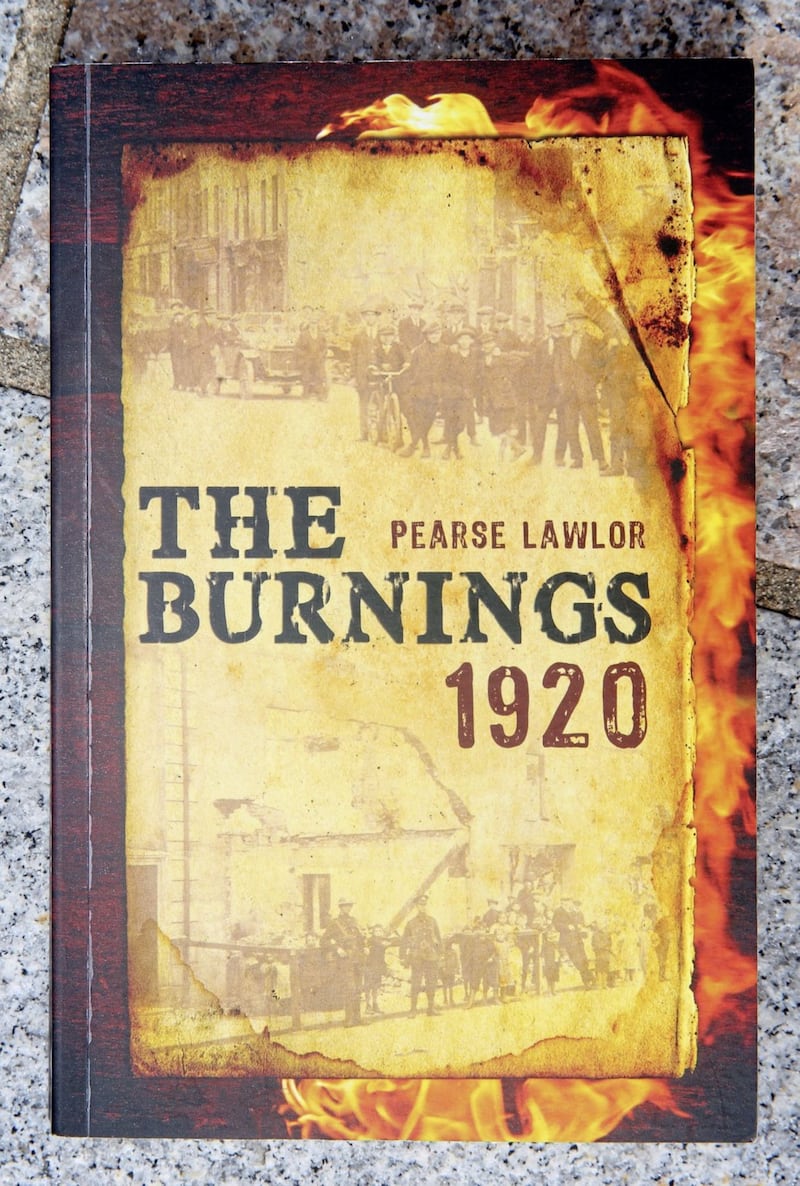

But Pearse Lawlor, author of The Burnings 1920, said the violence of that year, which eventually petered out at the end of September, was never really talked about in Lisburn.

“When this ended it was erased from history," he said.

“I would talk to Protestants in Lisburn who are very well educated, they have vague ideas of what happened.

“They did not know the background or the extent.

“You could not walk down the main street for flames coming from shops.

“It was forgotten about on purpose.”

Mr Lawlor, who is from Lisburn, said Catholics in the area were also subjected to intimidation prior to 1920.

Gaelic games were forced from the district in 1904 and did not return until the 1960s.

But he said the violence 100 years ago this month had a lasting impact.

“It certainly changed the dynamic of Lisburn,” he said.