Of all the things I thought I’d be doing on my daughter’s sixth birthday; listening to her final breath as she died was not one of them. But the last few years have brought plenty of unwelcome surprises.

First, we noticed Bella’s loss of appetite. Then the mood swings, constipation, and leg pains.

Several trips to the GP later, we still had no answers. When Bella developed a limp, it changed everything. We took her to A&E, where we were told she was anaemic.

She was admitted for tests to identify the cause of the anaemia, and by Friday November 13, a day for ill omens, we found out Bella had developed Stage 4 High Risk Neuroblastoma. In a word: Cancer.

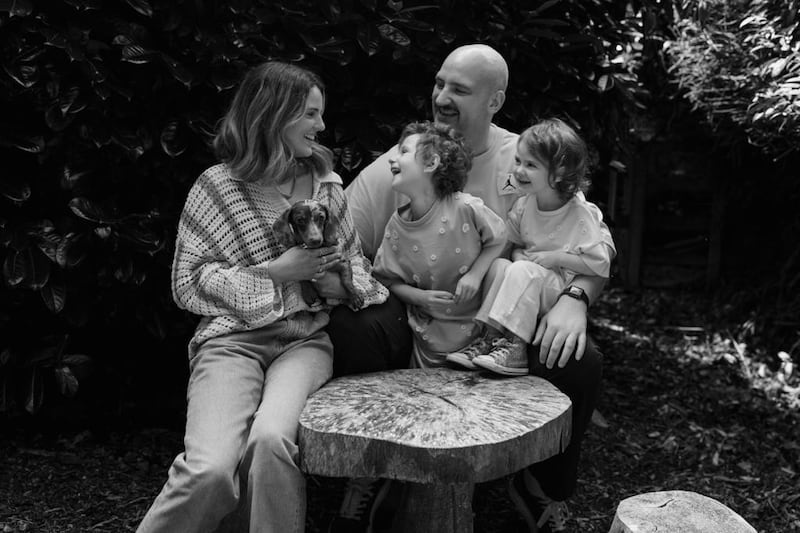

Myself, my partner Niamh, our five month old daughter Indie and the wider family circle were thrust into a world I believed to exist only on TV.

From admission to the beginning of treatment, Bella had already gone through so much. Within the space of four days, Bella had three anaesthetics.

One for an MRI, to identify a large tumour that had grown on her adrenal gland above her kidney. A second to take a biopsy of both her bone marrow and the tumour itself.

A third to place a Central Line in her chest, to simplify the infusion of medication and blood. The physicians outlined a 12-month treatment plan.

This was 2020, the height of the pandemic, meaning only one parent could be with Bella in hospital at any one time, and only if we registered a negative PCR test.

Niamh and I would try to joke that we were like passing ships in the night, Bella spent so much time in the hospital that it is hard to think of time that we spent together as a family.

Bella’s life became a series of cancer treatments: induction chemotherapy, high-dose chemotherapy, surgery, stem cell transplant, radiotherapy, and immunotherapy.

This protocol is archaic; no adult should have to experience it, never mind a three-year-old girl. I don’t use the word archaic lightly, throughout Bella’s induction chemotherapy, she was given a drug called Cisplatin, created in 1844 and used as a treatment since 1978.

While it may be considered effective in destroying some cancerous cells, 75% of the children administered with Cisplatin will suffer from permanent hearing loss. For those who survive, a small price to pay.

But Bella remained steadfast. Niamh and I complained more about the 300 nights spent in a hospital room, the multiple trips to hospital a week, the oral medication, the injections, the blood transfusions, more than Bella ever did.

Other than developing a fungal infection which kept her in hospital for six weeks, we received favourable news at each stage. By February 2022, there was no sign of disease and Bella rang the bell in the hospital ward to mark the end of treatment.

We celebrated and enjoyed time with our healthy daughter, glad to put the horrors of cancer behind us. However, we were never naïve to the fact that Stage 4 HR Neuroblastoma comes with a relapse rate of 50-60%, most of which will happen within the first two years after treatment.

Sadly Bella’s relapse came a lot sooner and in April, the results of Bella’s follow-up scans showed the disease had returned. Bella restarted treatment. Over the next nine months we trialled three different combinations of chemotherapy, all with limited results.

The toll of frontline treatment was obvious, as Bella’s blood counts would not recover at the rate required between each cycle of chemotherapy. We had one last roll of the dice: an experimental trial in Glasgow. But after only a few weeks, Bella’s blood counts dropped and she defaulted on the trial.

The landscape for relapsed paediatric cancer is bleak, and there is a heavy reliance on trials. Unfortunately, trials come with criteria, and regardless of how desperately someone may need the treatment, if they do not meet the criteria, they cannot access the medication.

We then learned in June the disease had spread to her brain, and there were no remaining treatment options. The prognosis suggested Bella had a few months left, if we were lucky. She died 10 days later.

Bella’s death certificate states that she died from neuroblastoma, but I wholeheartedly believe it was a lack of viable treatment options that killed her.

The severity of the current treatments are so antiquated, so ravaging, that a child’s chance of survival is reduced even further. Figures from the National Cancer Research Institute show that around $700 million is spent annually on cancer research, but only $15 million is dedicated to childhood cancer projects.

In the last six years, 77 new drugs have been made available to treat adult cancers. In the last 77 years, only three have been made available for childhood cancer. It is true, more adults are diagnosed with cancer than children. However, Relapsed HR Neuroblastoma has a 5% survival rate, some other paediatric cancers have a survival rate as low as 2%.

Prostate Cancer has a 98% survival rate and receives 5% of all funding dedicated to cancer research, more than double that allocated for the entirety of childhood cancers. Many of the childhood cancers are isolated only to children and without the ability to fully research them, there will continue to be a gap in diagnosis, treatment and prevention.

While this is true for many of the childhood cancers, we have no understanding of why children get neuroblastoma.

Something must change. Even for children who survive, the non-specific treatment they receive results in lifelong physical, mental, and emotional challenges.

The knock on effect from treatment, takes an irrevocable toll on children’s bodies that can drastically reduce the success of any further treatment needed.

Bella fought without the tools she needed to win the battle. I never wanted to be at her bedside as she died, to plan that speech for her funeral, or live the rest of my life without her.

Roughly 2000 children are diagnosed with cancer across Ireland and the UK and approximately 300 will die annually. However, the traumatic waves created by a diagnosis or death ripple far beyond what simple statistics can illustrate.

There hasn’t been an hour that has gone by since she passed that I haven’t thought about my daughter. A lot of the time the thoughts are sad, tears spontaneously coming to my eyes as I think about the days, months and years that lie ahead without her.

Other times, happiness, thinking about how lucky I was to share six years with her. What often rears its head is anger, at the thought of how preventable her death could have been. Bella won’t be the last child to die from cancer. But increased awareness and dedicated research will reduce that number.

It will prevent children from going through a cancer journey, simplify the diagnostic process and ensure kinder, more abundant and more successful treatment options.