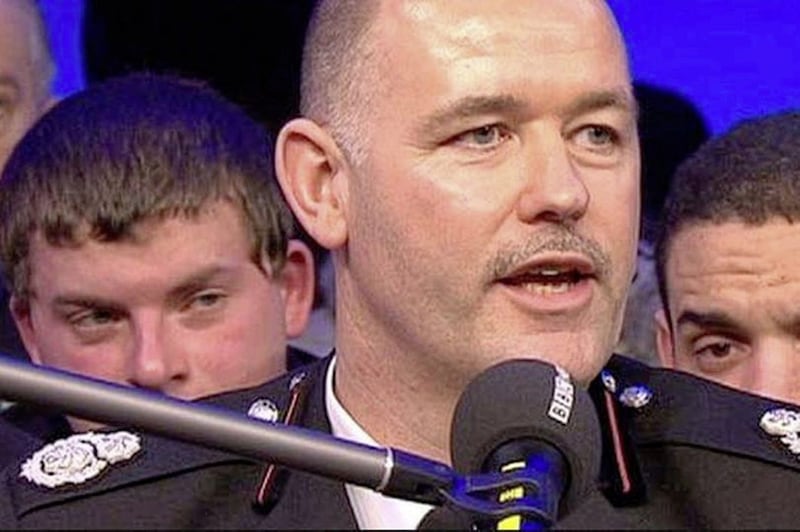

THE Belfast-born former head of Manchester’s fire service has broken his silence to defend its response to the arena suicide bombing which killed 22 people.

Peter O’Reilly, from the Andersonstown area of west Belfast, was chief fire officer at Greater Manchester Fire and Rescue Service (GMFRS) at the time of the terror attack.

A report into the emergency response, published in March, was critical of the service’s actions in the immediate aftermath of the blast.

It said communication problems meant crews took two hours to attend the scene of the bombing at an Ariana Grande pop concert on May 22 last year.

Mr O’Reilly served in the Northern Ireland Fire and Rescue Service for more than two decades including tense periods during the Troubles.

He moved to GMFRS in 2011 and became chief fire officer in 2015. He retired this year.

Mr O’Reilly said he thinks every day about the 22 people killed in the Manchester Arena attack and will “always regret” that fire crews were not there within minutes.

But he said the fire service was left in an “information vacuum” because Greater Manchester Police (GMP) did not follow established protocols and national guidelines on how emergency services should work together during terror attacks.

He said that amid reports of a possible ‘active shooter’ at the scene, police did not liaise with fire and ambulance officials to help them assess the threat level and deploy crews accordingly.

This led the fire service to hold back, assembling at a distance in case of an escalating firearms attack.

Mr O’Reilly criticised the Kerslake Report’s examination of the emergency response, saying it failed to properly question how police acted against guidelines.

In his first interview since the bombing, he told The Irish News: “I have no doubt that had proper protocol and policies been followed, the firefighters of GMFRS would have been at the Manchester Arena within minutes of the bomb exploding.”

The 51-year-old said fire crews had received medical training from North West Ambulance Service paramedics and “should have been put to use to help those in most need – but they weren’t”.

“For me, I will always regret that the fire service weren’t there within minutes. Every one of these firefighters was trained to help these people in their darkest hours and that was taken away from the fire service to be able to do that,” he said.

“On the night in question, I believe the fire service should have been there. We had worked very, very closely with our colleagues in the ambulance service to train our firefighters up. We had trained our staff up to respond to terrorist attacks.

“They weren’t able to do that, simply because police didn’t live up to their responsibilities of having a conversation with the fire service. If they did, we would have been there.”

Thousands of concert-goers – many of them children – were streaming into the arena’s foyer after the performance when suicide bomber Salman Abedi detonated a home-made explosive device at 10.31pm. More than 700 people were injured. It was deadliest terror attack in Britain since the London bombings on July 7 2005.

In the early minutes after the Manchester bombing, the fire control room received information from police that there were reports of an ‘active shooter’ at the scene.

Although this information was erroneous, protocols in this scenario required the fire service to contact GMP’s force duty officer to assess the threat. However, Mr O’Reilly said the fire service was unable to make contact with the duty officer or other senior officers.

With the lack of communication, the fire service stuck to guidance by assembling crews at a distance from any potential danger zone.

Mr O’Reilly defended this approach. He said that had firefighters been deployed to the scene of an ‘active shooter’ without proper information, there was a “significant risk that firefighters could have been shot and killed”.

Meanwhile, police had declared the incident Operation Plato – the codename for multi-agency protocols which are supposed to kick in when there is a belief that semi-automatic weapons are being used indiscriminately. However, neither the fire service nor the ambulance service were told of this.

Mr O’Reilly was asleep at home when he received a phone call about 37 minutes after the attack. He arrived at headquarters at about 11.45pm.

He said he was “horrified” to discover that his crews were still not at the scene.

“GMFRS was in an information vacuum,” he said.

The first firefighters arrived at 12.37am after Mr O’Reilly phoned a senior ambulance service official offering help.

Lord Kerslake’s independent review found the poor communication meant the fire service was “effectively outside the loop” and “brought to the point of paralysis”, to the “immense frustration on the firefighters’ faces”.

But it said GMP’s coordination of the response to the attack “worked effectively”. It did not criticise the duty officer but recommended reducing the load placed on them during major incidents.

In reviewing national guidance, the report said it “appeared odd” that “so much weight was placed in the doctrine on the importance of a single inter-agency connection and, therefore potentially, a single point of failure”.

Mr O’Reilly disputed the report, saying it was unfair towards the fire service and he felt it “exonerated” police.

Mr O’Reilly said it has taken him more than a year “to have the strength to talk about all this without being extremely emotional about it”. He said he hopes the inquests into the deaths will properly examine the events of that night.

GMP declined to give further comment but Chief Constable Ian Hopkins has previously said that “when faced with an unprecedented situation everyone in GMP did their best to help all those affected”.

Responding in relation to the Kerslake review, Greater Manchester Combined Authority said the review “makes recommendations for all emergency services, including police”.

A spokeswoman said: “Police, fire and rescue and ambulance services are all required to respond according to the principles of the Joint Emergency Service Interoperability Programme – the first two of which are collocation and communication.”