Cancer cells will be heading to space as part of UK scientific experiments to understand more about an incurable childhood tumour.

Researchers from The Institute of Cancer Research are sending samples of diffuse midline glioma to the International Space Station (ISS) to see how it spreads in microgravity.

The scientists said their study – dubbed D(MG)2 – could pave the way to understanding more about the disease that led to the death of Karen Armstrong, the daughter of late US astronaut Neil Armstrong.

Chris Jones, leader of the D(MG)2 study and professor of Childhood Cancer Biology at the Institute of Cancer Research in London, said: “Unfortunately, survival rates for patients with diffuse midline glioma have not changed substantially since Neil Armstrong’s daughter died of the disease in the early sixties.

“The last 15 years, however, have revolutionised our understanding of the biological complexity of these tumours, with exciting potential new therapies entering clinical trial at last.

“Experiments such as D(MG)2 aboard the International Space Station will improve our understanding of how cancer cells interact with each other within three-dimensional structures, and hopefully lead to new ideas for disrupting tumour growth that we can take forward back in the lab.”

Diffuse midline glioma is an aggressive and incurable brain tumour that most commonly presents in children.

It has a poor prognosis – most children die within 18 months of being diagnosed.

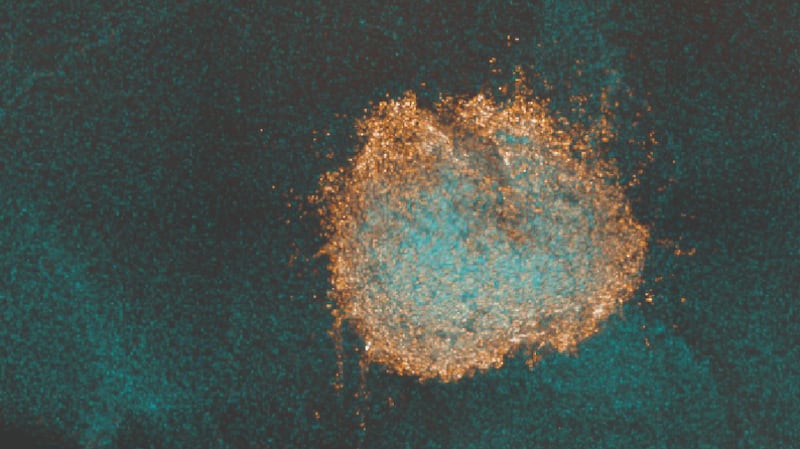

The researchers want the experiments to be conducted in microgravity because they believe the conditions will allow their 3D cultures to grow to much larger sizes than on Earth.

This will allow much larger extensive models in which to study how cancer cells interact – as this interaction is thought to drive growth, the team said.

While microgravity can be recreated on Earth, Prof Jones said the conditions “can induce some mechanical stress on the cells which may change how they behave, which we want to avoid”.

The D(MG)2 study has received £1.2 million from the Government while another study, MicroAge II, led by the University of Liverpool, was awarded £1.4 million.

MicroAge II is currently investigating how the microgravity environment makes astronauts’ muscles weaken in space.

Equipment for the experiments is built by microgravity hardware specialists Kayser Space, based in Oxfordshire.

George Freeman, minister of state at the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology, said: “Space is the ultimate laboratory testbed with British scientists and astronauts harnessing the International Space Station for cutting edge research in nutrition, energy and biomedicine.

“This £2.6 million project funding will help UK scientists research how to prevent brain tumours in children, and understand the biomedical processes of ageing: research with huge benefits for mankind and health systems around the world.

“Another example of the way UK strengths in different sectors from space to life science and cleantech drive technology leadership.”

The launch is expected to take place in 2025, and experiments will be conducted by astronauts on board, with samples expected to be returned to Earth about six months later.