Animals were being farmed for food as early as around 13,000 years ago, an analysis of ancient dung suggests.

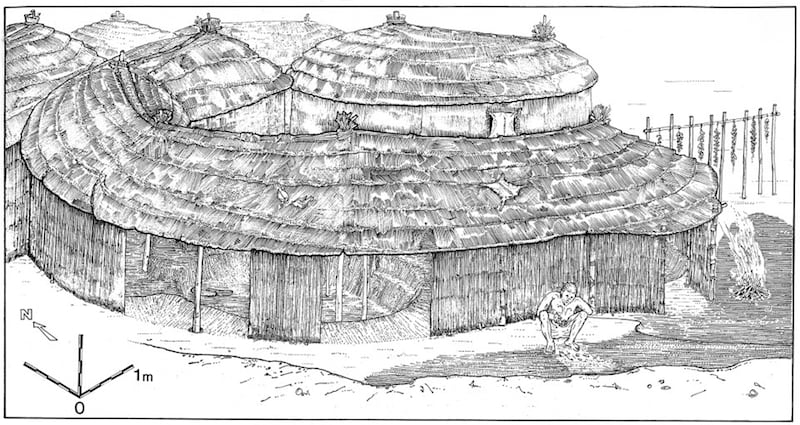

According to researchers, hunter-gatherers living in Abu Hureyra – the Upper Euphrates valley in Syria – were bringing sheep and other live animals and tending to them outside their huts thousands of years ago.

Professor Alexia Smith, of the department of anthropology at the University of Connecticut in the US and one of the authors of the study, said: “This is almost 2,000 years earlier than what we have seen elsewhere, although it is in line with what we might expect for the Euphrates Valley.

“As hunter-gatherers began to experiment, bringing live animals to the site – even if it was for a short period of time – they would have had no idea of the massive societal changes they were setting in motion.

“The way we live today rests heavily on this shift from a reliance on hunting and gathering wild plants and animals to a dependence on growing and herding our food.”

An international team of researchers, which included scientists from the University of Durham, analysed soil samples gathered from Abu Hureyra, which is now a prehistoric archaeological site.

The samples were collected by a team led by Professor Andrew Moore, of the Rochester Institute of Technology in the US, during excavations at Abu Hureyra in the 1970s.

The scientists looked at substances present in the soil known as dung spherulites – tiny balls that form in the intestines of plant-eating animals before being excreted from the body as part of dung.

These spherulites allowed the team to approximately date when the dung deposits were made, which is somewhere between 12,800 and 12,300 years ago.

The dung is thought to be from sheep – one of the earliest animals to be domesticated.

Emeritus Professor Peter Rowley-Conwy, from the department of archaeology at Durham University, who contributed to the research by studying animal bones from Abu Hureyra, said: “The people living at Abu Hureyra at the time were tending the very earliest domestic sheep which were small-scale household animals, not a big herd like we might expect to see today.”

The researchers say that hunter-gatherers in that region began to “increasingly rely on sheep to supplement a diet based mostly on hunted gazelle, although they also caught small game such as birds, hare and fox”.

Then eventually, by the Neolithic period, which is between 10,600–7,800 years ago, herded animals such as sheep and goats became more important than hunted ones.

In addition, the findings, published in the journal PLOS One, also provide further information on the ways people lived in the past.

Evidence from the Abu Hureyra site suggests that as the dung built up outside the huts of the hunter-gatherers, it was put to use as a fuel.

Prof Smith said: “When dung is burned, it gives off a steady, high temperature that can be used to cook and provide light and warmth.

“During the Neolithic period, when dung accumulations were even more abundant, people used the excess as a building material to help create plaster floors.

“Dung continues to be used as a fuel and a construction material in many parts of the world today.”