Q: After any meal, regardless of the time of day or what I’ve eaten, I have to cough to clear my throat of food and drink. I’ve put up with this for years, but now believe it is a medical problem rather than normal. Can you give me any advice to help?

DS

A: From what you describe, it sounds as if you have a type of dysphagia — in other words, difficulty in swallowing.

Normally, when we swallow, a set of automatic muscular movements kicks in, contracting in a co-ordinated way to move the food and drink down from the oesophagus (or gullet) into the gut.

However, sometimes — often as a result of pressure on the valve between the oesophagus and the stomach — food or drink spills back up, causing acid reflux: this can irritate the oesophagus and even spill into the throat, causing the cough.

You mention in your longer letter that you haven’t experienced any acid reflux.

In fact, sometimes the only sign of acid reflux is a cough (known as silent reflux), although in your case this seems unlikely as your symptoms occur while food and drink are still in your throat.

One possibility is a Zenker’s diverticulum, essentially a bulge in the wall of the oesophagus.

This is more common in older men — we don’t know why: it can be ‘silent’ (i.e. symptom-free) or may cause a variety of symptoms, including difficulty in swallowing, a cough, or regurgitation of food back into the mouth. It can be repaired with surgery.

In any event, I suggest you need to be referred to a gastroenterologist or an ear, nose and throat specialist, who can check for this and other potential causes.

The standard investigations for such problems are a barium swallow X-ray (where you are X-rayed while swallowing a thick liquid that shows up on the screen, to reveal any abnormality such as a Zenker’s diverticulum) and an endoscopy (where a camera on a flexible tube is used to inspect the throat and upper oesophagus).

Both are simple outpatient procedures — the barium swallow X-ray is the best first-stage investigation.

Q: Following a nine-hour flight in 2015, I suffered a pulmonary embolism and ended up in hospital in Barbados for a week. I’m about to take the same flight and am worried about it happening again. Is there anything I can do to put my mind at rest?

LM

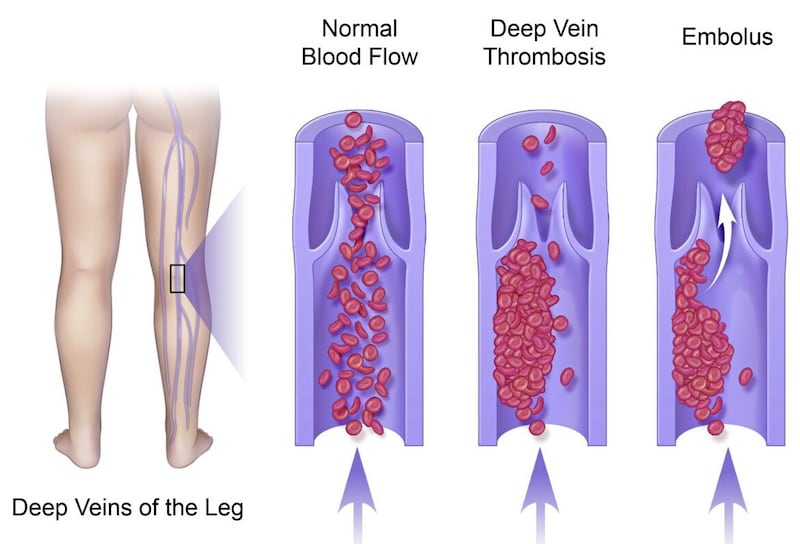

A: For those readers not familiar with the term, a pulmonary embolism is a clot that blocks blood flow in the arteries within the lungs.

These clots most often start in a deep vein in the leg, and they are a risk for any long-distance traveller, as being stationary for so long means the blood can pool in the veins, which can lead to a clot forming. The clot can then travel to the heart and, from there, reach the lungs.

As you note in your longer letter, having once experienced a pulmonary embolism, statistically you are at greater risk of having another (we don’t really know why this is so).

The first clot occurred despite the sensible precautions you took — wearing compression socks and walking up and down the aisle regularly during the 2015 flight.

Furthermore, your mobility is now reduced, you say, following a couple of falls in recent years.

Given your history, I think it would be advisable to have a preventive injection of the blood-thinning drug heparin or enoxaparin (brand name Clexane), a newer type of anticoagulant.

Clexane is prescribed in a pre-loaded syringe so you can inject yourself.

I would recommend an injection the day before you travel and the second dose on the day of the journey. You will also need a supply to be used at the time of your return. (This might seem daunting but practice nurses and GPs are well versed in teaching patients how to deliver the injection.)

Personally, I would not allow any of my patients who have previously had a pulmonary embolism to undertake any journey longer than four hours, whether by car, coach, train or aircraft, without this highly effective protective measure.

I suggest you take advice from your GP well ahead of your flight so you can be fully prepared.

© Solo dmg media