I'VE thankfully spent my life looking forward rather than back, but it would be remiss of me not to note the 50th anniversary of internment just past and the impact it had on so many families, including my own.

In the early hours of 9th August 1971, army jeeps pulled up at the front of my home in north Belfast. It was the start of internment and, as with so many other homes that night, British soldiers had come to take away a father without charge, trial or conviction.

Upon opening our front door, my dad was faced with 12 heavily-armed blacken-faced soldiers. The officer in charge handed him a letter signed by Brian Faulkner ordering his internment.

At that moment, across Northern Ireland, men were being dragged from their beds, beaten and thrown, half-naked, into jeeps. My father's treatment in comparison was mild, no doubt because of the fact he was a Belfast City councillor. He may be the only example in UK history of an elected representative being interned.

A man of some gravitas and not easily intimidated, having cordially thanked the officer for the safe delivery of the letter, Father invited him to make himself comfortable as he got ready. He then returned upstairs where he took his time shaving and dressing.

He was transported to the chapel in Crumlin Road Gaol being used on August 9 1971 as a clearing house before prisoners were transported on, in my father's case, to Long Kesh, later re-named The Maze.

My only memory of his internment involves a visit there aged 10. I was struck how everything seemed grey and remember being a little afraid when searched by a soldier on the way in.

We were brought to a small room where Father sat waiting. I don't think I got a hug, but then again, he wasn't a 'huggy' sort of dad. The female soldier who'd searched my mother hadn't done a great job as she surreptitiously removed four miniature bottles of brandy secreted in her bra, which Father hastily consumed.

While I was old enough to understand he couldn't come home as he was in prison, I was confused when then told he was an innocent man who'd committed no crime. These contradictory statements were hard to reconcile in the mind of a 10-year-old; they remain hard to reconcile in the same mind, 50 years later.

Father seldom spoke about his past; most of what I know I've learned second-hand, either from books or talking to men who knew him. One such serendipitous encounter occurred when my accountant introduced me to his uncle, Bobby Quinn, who'd been interned in the same hut as Dad.

He told me that on Christmas Eve 1971, my father was brought to the camp gates where an army officer informed him he could be released immediately; all he needed to do was sign the document they'd placed in front of him.

This document originated with the Brown Tribunal, an advisory committee set up by the Faulkner administration ostensibly to arbitrate the release of prisoners. The document asked he swear to "never join any illegal organisation or engage in violence against the state".

Dad rightly viewed such a declaration as a tacit admission of previous guilt and refused, saying he'd broken no law to be arrested and would sign no letter to be released. He was brought back to his hut where he was to languish for another four months.

He received scant support from his fellow councillors, with one Unionist sarcastically commenting "Councillor O'Kane, he's a good friend of mine – if he was being hanged, I'd buy the rope". The Council stripped him of his seat whilst he was incarcerated, citing grounds of 'non-attendance'.

Crumlin Road Gaol is long closed and has now been transformed into a tourist attraction. The old chapel where my father was taken on in 1971 is now a theatre and it was onto its stage I walked, several years ago, whilst on my end-of-year tour.

With a palpable sense of a circle being closed, I began that show saying, "I'm the third member of my family to appear behind these walls, but the first one to do so voluntarily". I hope the laughter that night helped to exorcise some of the sorrow, pain and suffering trapped within that prison's foreboding edifice.

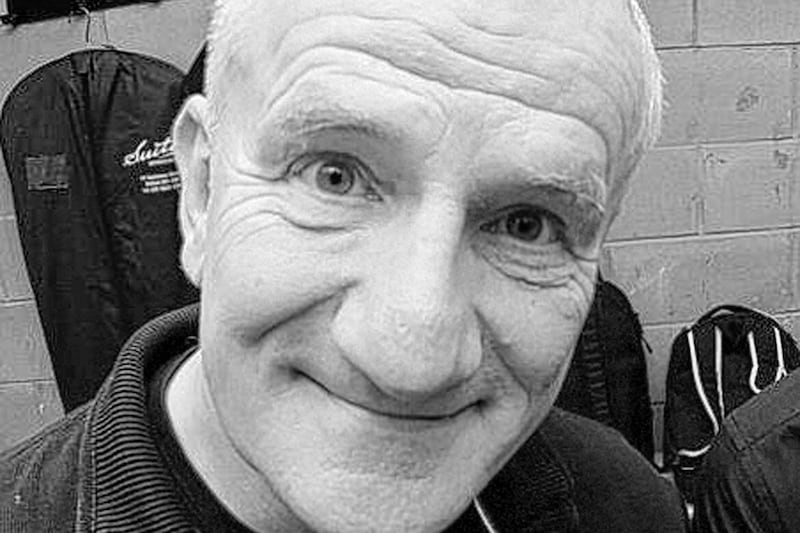

In memory of my late father, councillor and internee, Jim O'Kane: released from internment in April 1972 having never been charged, tried or convicted of any crime.