WHEN noted British travel writer Jan (originally James) Morris anticipated her obituary, she said it would undoubtedly be headed 'Sex change writer dies', which she felt would be vulgar. As her Northern Irish biographer Paul Clements explains, things turned out better than expected: "All the headlines read 'Trans pioneer dies'."

It was, whichever way you headline it, an extraordinary life. And it is extremely well documented by Clements in Jan Morris: Life From Both Sides, published by Scribe this month.

The writing of this extremely readable 600-page book has been a labour of love.

Clements (65) knows the career of the writer who out-Palins Palin inside out. He respects the author's insistence on the feminine personal pronouns, used retrospectively. He says he first got to know Jan Morris's work as a young man when he was living in a flat in Omagh, after his widowed mother had sold her draper's shop and remarried.

The BBC man was starting his career as a journalist on the Tyrone Constitution.

"I became interested in her in the late 70s after picking up her book Travels (1976) in a second-hand bookshop," he recalls.

"I was a journalist doing everything at the time – births, deaths, court reports."

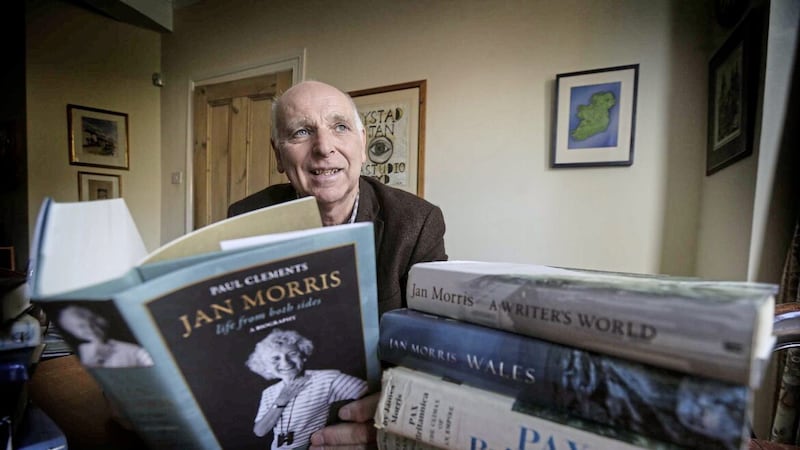

This tome fits snugly into the Jan Morris bookcase in Clements's spacious study in his south Belfast home.

If it is a semi-shrine, it's one dedicated to great writing. Interestingly, a Lisburn man, Charles Monteith, talent spotted Morris for Faber. Clements says that he was immediately drawn to Morris's style: "We'd only done things like Dostoevsky at school and this was a friendly, personable style."

It was also, of course, quite flowery at times and Clements made an interesting discovery once he'd started the detailed research for his first book on Morris.

This was a slim volume, one of the University of Cardiff's Series on Writers from Wales. By now friends after Clements wrote Morris a fan letter, asking if she would sign his collection of her books, they nearly fell out over Clements's cheeky inclusion of a couple of the writer's early poems.

A student at the Sussex public school Lancing, James Morris had penned some high-falutin' verse for the school magazine.

Mid-career, Clements, who didn't have time to fit in a degree earlier on, won a Reuters scholarship to Oxford. This enabled him to spend a year where Jan Morris was educated.

She studied English at Christ Church, the largest and grandest of Oxford colleges. One day, Clements made a thrilling discovery in the stacks of the Bodleian Library.

"I was there every day, among the maybe million or so books they have," he tells me.

"I wasn't looking for it, but in the bowels of the building I came across the Lancing school magazine produced during the war."

Turning the pages, Clements came upon the verses by Morris. He included them in his book but when out of courtesy he showed Morris the proofs, he got a salty response. She vigorously crossed out the pages in black ink.

Yet, as Clements points out, these verses paint a picture of the time. One describes an air raid attack and contains the lines:

"Choose carefully, pilot of the fates;/Pause, consider where you drop your bombs -/Listen closely for the hypocritical hymns/While mark where, clothes in spotless coats/The enemy's foul tidiness pulsates."

An early, biased picture of the Germans as placers of neat towels on the hotel sunloungers, but relevant.

"I kept one poem, but Jan didn't bear a grudge. Although I didn't hear from her for a year, which wasn't unusual, she then wrote to me saying she'd liked the book," Clements says.

Questions of style dogged the future bestselling author who read English at college. Jan Morris studied under the noted don J.I.M. Stewart, also a thriller writer. Clements found his comments on his student's essays.

"I came across some papers, including notes on Jan's student work. He said she had a forceful style with too much affection in it which didn't serve her arguments well."

Amusingly, Stewart had, in the way of professors, marked his student down for this. Yet her writing style would make her name, career and eventually bring fame and if not fortune, a more than decent living.

Morris's Pax Britannica, about the colonial legacy, published in 1993 is still in print. And Morris was a genuine bestseller, chalking up 500,000 sales of the autobiographical title, Conundrum.

In his biography, Paul Clements quotes from one of Morris's best known introductions, the one which opens Venice, her magnificent book on the iconic Italian city.

This and her book on Oxford, named simply Oxford, graced many homes from the sixties onwards and it's not hard to understand why.

She wrote this characteristically quirky opening: "At 45°14' N, 12° 18' E, the navigator, sailing up the Adriatic coast of Italy, discovers an opening in the long low line of the shore: and turning westward, with the race of the tide, he enters a lagoon. Instantly the boisterous sting of the sea is lost. The water around him is shallow but opaque, the atmosphere is curiously translucent..."

Clearly not an academic style but it places Morris at the top of a school of travel writers, maybe old school but including the Eric Newbys and Patrick Leigh Fermors of this world.

Morris trained as a journalist after Oxford and joined The Times after the Second World War, becoming their star reporter. In 1953, she joined Edmund Hillary's attempt to conquer Everest and when he reached the summit, filed reports that enabled her to reach global recognition.

The only reporter on the expedition, she noted in rare understatement from Camp IV that a trudge through snow and ice was "extremely unpleasant". Never having climbed a big mountain before, Morris asked John Hunt whether it was usual to feel breathless at 17,000 feet.

Although the editors at The Times complained that Morris didn't file often enough, her reports were eagerly followed round the world. It was not an easy task and the journalist had to pay runners, who took her copy away from Everest to a collection point, nearly £300 a pop in today's money. This was a kind of pinnacle, but Morris always wanted to write books.

The Times did not allow its journalists to publish books so she moved to the Manchester Guardian, asking editor Alastair Hetherington if there was an opening.

Not immediately, he replied, even for a star writer. But something turned up and Morris gained her perfect writing gig, six months reporting and six months writing books.

Literary fame followed. Charles Monteith, educated at Inst in Belfast and Magdalen College in Oxford and an extremely talented literary publisher with TS Eliot's outfit, Faber & Faber, came across the new writer.

He had wanted to turn Morris's Everest reports into a book and was sorry when he couldn't shift The Times' embargo. "I needn't say how sorry I am," he wrote to Morris. But his offer to look at any future writing bore fruit.

The Lisburn man, rightly known at Faber for his acuity, talent spotted an incredible panoply of talent, including Seamus Heaney, Philip Larkin and Paul Muldoon.

While Morris's wife, loyal and loving Elizabeth, knew from the outset that her husband, with whom she had five children, felt born in the wrong body (and liked to wear women's clothes sometimes), she had to divorce him when he changed sex.

They later remarried and finished their lives together in contented domesticity in Wales. They referred to themselves as sisters-in-law.

How did Clements feel about covering this? He knew he had to face up to it, as Jan herself had done. Clements comments now, looking at the fabulous cover image on his biography of Jan Morris in stripey summer dress, her hand to her neck.

"Was she trying to cover her Adam's apple? Who knows, but Jan said she was aware from a very early age, four or so, that she was born into the wrong body," he says.

Morris's gender journey was genuinely pioneering. Clements's account is both factual and sensitive. He says the Italian doctor who would perform realignment surgery in 1972 said to Morris the night before she would enter theatre as Mr, re-emerge Miss. People had died after this operation, and this was a truly brave move.

When discussing her predicament, Morris writes that it was connected to her passion for travel: "I have only lately come to see that incessant wandering as an outward expression of my inner journey. I have never doubted thought, that much of the emotional force, what the Welsh call hwyl, that men spend in sex, I sublimated in travel – perhaps in movement itself – as I have always loved speed, wind and great spaces...".

It was also brave in terms of public opinion. But Jan Morris successfully weathered the storm and went on to produce many more books, making a final tally of over 40, including a novel.

In her memoir, Conundrum, she writes about visiting Africa, employing the writing technique that her biographer describes as "taking the reader by the hand". Here she is on wart-hogs. "In a Kenya game park once I saw a family of wart-hogs waddling ungainly and in a tremendous hurry across the grass."

She could not help laughing, then added that her African companion rightly rebuked her. "You should not laugh at them... they are beautiful to each other."

:: Jan Morris: Life From Both Sides by Paul Clements is published by Scribe Publications on October 13.

The author will be in conversation with Noel Thompson at a special launch event at Waterstones in Belfast city centre on October 20 at 6pm.