Quite a few of the greatest artists, from Vincent van Gogh to Edvard Munch (who painted The Scream from personal experience of intense anxiety), suffered from mental ill health.

The latest research shows that painting, drawing and photography don't just lift the spirits but can have a curative psychological effect.

This is a significant trend and coming up from next week there are not one, but two, events underlining the positive effects of visual creativity on psychological problems.

The MAC is co-hosting with the Belfast Exposed photographic gallery a Healing Through Photography conference subtitled Seeing Through a Different Lens from April 3-4.

And artists Paul Doran and Niall Conlon have organised an exhibition under the title Minding Minds Together, running from April 21 at Ross's Auction House.

As well as their own pieces, the exhibition involves work by people attending the WAVE Trauma Centre and medical students at Queen's University. Doran and Conlon have also teamed up with muralist Mark Ervine to create a mental health themed mural in Belfast city centre.

It seems photography may actually provide a way through depression and anxiety. Belfast Exposed, the radical photographic gallery in Belfast's Cathedral Quarter, have discovered their workshops not only make participants better at taking photos, they can be tools in tackling mental illness and painful life events such as loss. It's called therapeutic photography.

As Mervyn Smyth, the gallery's community engagement manager, says: "Therapeutic photography as an art form enables a person to express themselves visually when they may find it difficult to express themselves verbally or in writing." He adds that there is something healing in the actual making of art.

As Smyth puts it: "When we have trauma, we look for something to help us navigate our way through. Art and in particular photography, can help us with this journey. People can rescript their trauma with new images that assist in healing."

He adds that taking photos can help those in the workshops to better express their thoughts and feelings: "Sharing these with others can in turn increases their confidence and self-esteem."

The conference features talks on all aspects of this fairly new approach, including an important contribution from former Irish News and Pulitzer prize winning photographer Cathal McNaughton who won the award for his harrowing coverage of the Rohingya massacre of refugees fleeing Myanmar. He will discuss his own trauma following this commission.

Artists Doran and Conlon have been working with the WAVE Trauma Centre on a project also aiming to help people through post-traumatic stress disorder.

The long spectre of the Troubles is among the reasons Northern Ireland has a very high incidence of mental ill health, with 70 per cent of adults experiencing at least one mental health problem. We also have one of the highest rates of post-traumatic stress disorder in the world, ahead of many war-hit regions in the Middle East.

Doran explains: "We've conducted workshops with people at WAVE trauma centre, all of whom have lost somebody."

So how does creativity help heal mental illness? Partly as a way of expressing problems, partly through the surprising relaxation that can accompany the act of having to concentrate on something very difficult, that is reproducing an object that exists in 3D on the flat, two dimensional piece of paper or canvas.

Doran says he understands from personal experience the value of art in lifting mood. He spent the years running up to lockdown exhibiting in London, Dublin and Belfast. He worked with members of Andy Warhol's team on a project in Europe. His large abstract paintings contain intriguing narratives such as the gorgeous painting Street Choir, about the Troubles.

Yet he admits that in spite of the success and glitzy career, he felt at times down in mood and didn't exactly relish the solitary career path of a modern artist.

"I don't think I had clinical depression but wasn't entirely happy," he explains.

"I had downers and my mother, Maria, had a heart attack a year or so ago which was a shock, although she's fine now. I was travelling, working solo and it was good to come back home."

Doran (34) has worked with the Hallows Gallery on the Ormeau Road, where he mounted a joint exhibition last August with the artist he now shares his studio with, Niall Conlon (38).

They met after Doran spotted some of Conlon's arresting works online and now operate from the former café space in Ross's Auctioneers which has good light and high ceilings.

Conlon, a former stockbroker, came relatively late to painting. A student at Inst, he says that the expectation was that you'd enter one of the professions as a lawyer, accountant or doctor.

But he always wanted to be an artist. Having worked and lived in London for years, lockdown provided Conlon with an opportunity to make the move.

He did the right thing. The artist's canvases are colourful, use slightly primitive figures recalling artists like Matisse, bristle with energy and are thought provoking.

During our talk, a family friend of Paul Doran's enters and the talk is of London contacts, big prices, Kensington galleries. The artists are collaborating on a London show in September in the Zari Gallery, Fitzrovia, on the theme of mental health and creativity.

Conlon shows me a canvas, titled Scramble, he's recently sold to a celebrated mate, actor Jamie Dornan. It is spectacular and exudes energy. Conlon clearly has not just creative juices but a keen commercial sense and started out producing iconic, slightly Warholesque images of glasses of Guinness which sold well in the Irish market and elsewhere.

The two artists have curated an exhibition featuring art by WAVE Trauma Centre clients. It's a selling show with funds going to charities such as Aware NI, the charity that helps people with depression.

Doran and Conlon have also involved Queen's University's medical students, who study a module on mental health and creativity as part of their course.

Under the Minding Minds Together title, the work here is revealing and moving.

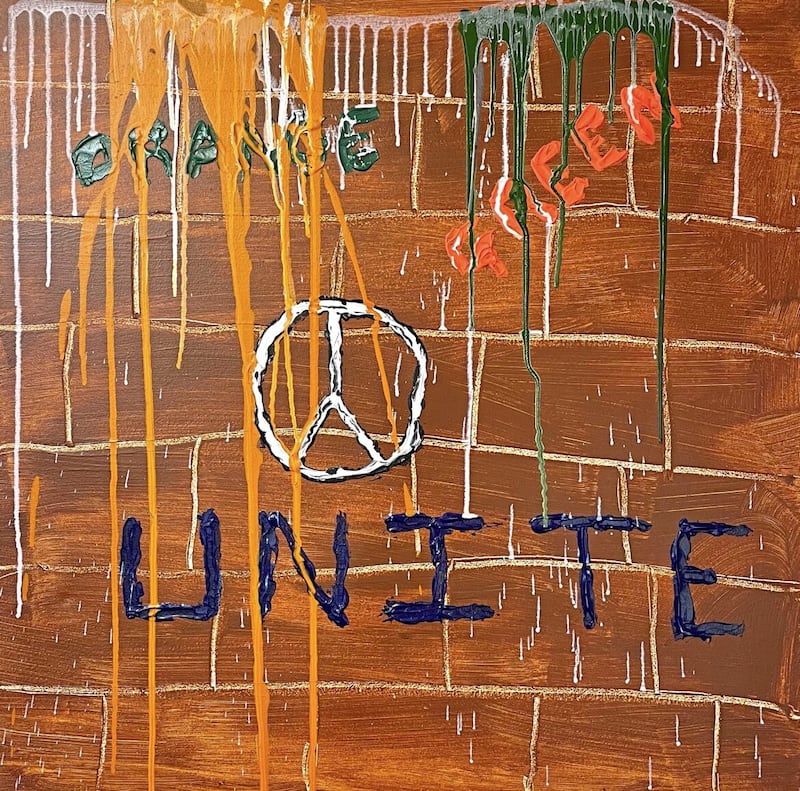

One man, Gareth, produced an impressive painting, Unite, showing a graffiti-laden brown wall with the peace symbol and the words 'orange' and 'green' spelt out. It's moving as the words for the colours that represent two sides of the divide that's caused the conflict wear opposition colours, with green in orange, orange in green. It is hopeful too.

As Doran says, it has been magical to work on this project with survivors. "Gareth said he'd never felt so comfortable in a workshop before, being with professional artists. Everybody has been affected by the Troubles, across the generations, and my father was from the Falls. My painting Street Choir shows the things I saw growing up. It was great to work with these people and we have a lot to learn from them."

Healing Through Photography: Seeing Through a Different Lens, Belfast Exposed at The MAC, April 3-4

Minding Minds Together, Ross's Auction House, Montgomery Street, Belfast, April 21 to May 5