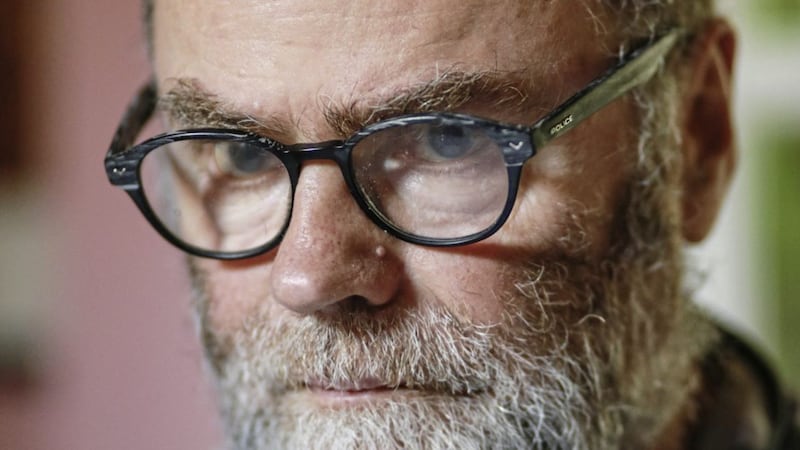

"ESSENTIALLY, the challenge I set myself was to go to as many protests in Northern Ireland as I could," explains Malachi O'Doherty of how penning his new book Fifty Years On: The Troubles and The Struggle For Change in Northern Ireland took him out on to the streets of Belfast and Derry to compare and contrast 'now' with 'then'.

Veteran journalist and commentator O'Doherty (68) was 18 when the Troubles first erupted and the book begins with his vivid recollections of running for cover as the RUC and IRA began trading machine-gun fire on the Falls in August 1969. A compelling mix of memoir, reportage and analysis, Fifty Years On digs into how the north's social evolution was almost derailed by decades of sectarian violence.

The key word there is 'almost': one particularly entertaining chapter of the book finds Co Donegal-born, Belfast-based O'Doherty imagining how he would attempt to explain how much Ireland has changed since 1969 to his younger self: that the once staunchly conservative Republic has embraced same-sex marriage and repealed its constitutional ban on abortion, that Sinn Féin supports the liberalising side of both issues in the north and that the prospect of a 'united Ireland' now seems closer than it ever was during the Provisional IRA's heyday thanks to the ongoing Tory-led and DUP-supported Brexit debacle.

"We had 30 years of trouble – routine killings and bombing," he writes, imagining how that conversation with 18-year-old Malachi might go.

"It seemed to be our normality. It became axiomatic to say that nothing ever changes here. Yet this society is transformed. There has been a revolution, but it is not the one the paramilitary armies fought for."

"Essentially, the argument of the book is that we did have a revolution, but it wasn't the one you saw on TV," says O'Doherty. "At one point, the book's proposed title was 'The Real Revolution'."

Having grown up on the Riverdale estate in Andersonstown and worked for the Belfast Telegraph, The Irish Times and The Scotsman right through the Troubles and its concurrent 'peace process', the author is well placed to offer insight into the changes he's witnessed.

"In the first section, reflecting on my own past and my own life and experience, some of that was quite hard to trawl up, but I'm used to writing memoir," comments O'Doherty, whose previous books include autobiographical tome The Telling Year: Belfast 1972 and Gerry Adams: An Unauthorised Life.

"But largely speaking, writing this book was fun. It's essentially a work of reportage. It meant a return to basic day-to-day journalism, going out and covering protest parades and interviewing people, and I enjoyed it immensely."

O'Doherty gained first-hand experience of protests and campaigns across a full spectrum of 'hot button' topics including LGBTQ rights, women's rights, abortion, the Irish language, dissident republicanism, loyalism, anti-paramilitary protests and policing – the latter's evolution from RUC to PSNI providing an interesting through-line for the book.

"If the modern PSNI had policed the October 5th march, there wouldn't have been the Troubles," he says, imagining how history might have been very different had the RUC chosen not to baton-charge civil rights marchers protesting about housing conditions in Derry in 1968.

"That's a pretty sweeping statement, but certainly the October 5th march and the way the RUC behaved was the big spark which got things moving, which takes you to Burntollet and to Newry and, ultimately, to August 1969."

In the book, O'Doherty recounts his often frustrating experience of attempting to educate young RUC recruits about the delicate nature of community relations in the 1990s prior to the reforms of the PSNI-era. It also allows readers to absorb how the 'art' of protesting has evolved over the past half-century here.

"In a sense, many of the protestors of today are more moderate," he notes of the preponderance of peaceful rallies. "There's a kind of disinclination on both sides for things to get violent or disruptive. At one of the Brexit protests outside Belfast City Hall, the police were being quite assertive while trying to prevent any overspill on to the roads.

"I remember thinking, in the most cynical way, if these people really want to be on the news tonight they should spill on to the road, block the roads and confront the police – because that's what gets results.

"It's what got results on October 5th. I mean, certainly the police were hugely incompetent and brutal in the way that they dealt with the parade, but people in the parade taunted them towards that. They knew that if the parade turned into a riot it would be better for their case. And so it was."

By way of illustrating just how much things have come on since the 'bad old days', O'Doherty cites his experience of attending Pride in Belfast.

"The gay protests like Pride are hugely celebratory," he notes. "I mean, as you'll see in one of the pictures that's in the book, the police are on their bikes in their high-vis jackets and it's almost like they're part of the party."

However, with dissident republicanism back in the news this week following a bomb blast at Wattle Bridge in Co Fermanagh which was claimed by the CIRA, the Troubles' legacy of violence rumbles menacingly on despite the myriad social changes we have witnessed since 1969.

In one chapter of Fifty Years, O'Doherty attends a meeting of Saoradh-affiliated dissidents at a Dundalk hotel, where prominent member Dee Fennell tells him how he is a committed republican who abides by Pádraig Pearse's infamous maxim 'England's difficulty is Ireland's opportunity'.

Fennell, the author writes, "anticipates that Brexit is just such a difficulty". With many commentators now predicting that the shortest path to a united Ireland is now via border poll in the wake of a hard Brexit, could Boris Johnson really be about to steal Fennell and co's thunder?

"If this [Brexit] goes badly in any way at all, I think we will ultimately find our way back into the European Union through a united Ireland," opines O'Doherty, who explains in the book how he has somewhat reluctantly come to terms with the British side of his own identity vis-a-vis growing up in Northern Ireland.

"I'm uneasy about it happening, but I'm uneasy about Brexit. My point is to simply say, whatever way it goes, we're damaged: I don't see a way in which we separate ourselves from London to go back into the EU without a sense of great loss – and we're blithe about that because we don't own up to our 'Britishness', to our attachment to Britain.

"Think of the number of Irish people there are in London. It should be a kind of light unto the rest of us of what a city can be in its complexity and diversity. It's a fantastic place and a global city. And it's also a 'remain' city.

"If you tell me London is my capital, I'm happy with that."

:: Fifty Years On is out now, published by Atlantic Books, RRP £18.99. There will be a launch event for the book on August 22 at Eason in Foyleside Shopping Centre, Derry, at 6.30pm, all welcome.