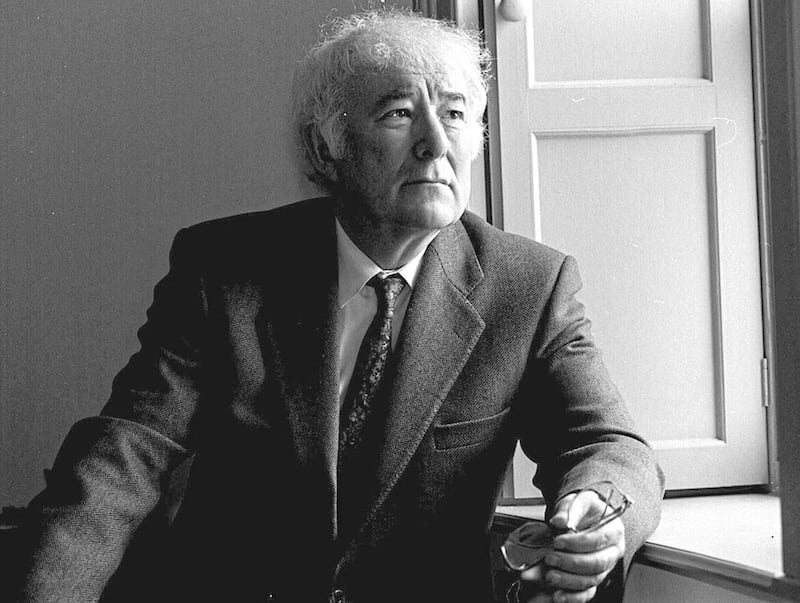

We were sitting in English class the day after it happened. Our teacher had just introduced us to the poetry of Seamus Heaney. Even for a group of boys more interested in football than poetry, it was revelatory.

Heaney – though drilled in the classics – spoke in our voice. The Ulster vernacular tumbled from his pen. The imagery was imagery we could relate to.

The “rat-grey fungus” that consumed summer blackberries; the “squat pen” of Digging; and the fateful line from Mid-Term Break where he describes his brother’s coffin: “A four-foot box, a foot for every year.”

We were about to have a mid-term break of our own. The class was interrupted by an announcement that the school was to close, and we were to make our way home. Not even the practice of education was dignified enough when the bodies of those murdered on Bloody Sunday were lying in their coffins.

Heaney was among those who attended their funerals, and he commemorated them in a powerful lament. The Road to Derry does not pull its punches: “The Roe wept at Dungiven and the Foyle cried out to heaven/Burntollet’s old wound opened and again the Bogside bled.”

- Analysis: Truth matters to Bloody Sunday familiesOpens in new window

- Bloody Sunday disappointment another reminder of how the pursuit of Troubles truth and justice has been left behind by the Tory legacy act - The Irish News viewOpens in new window

- The use of injustice to hold on to power is endemic in the British state – Tom CollinsOpens in new window

The poem ends with justice in the gutter and the hope that, in time, it would be restored.

“And in the dirt lay justice like an acorn in the winter/Till its oak would sprout in Derry/where the thirteen men lay dead.”

Fifty years on, it is difficult to argue that much has changed. Yes, the dead of Bloody Sunday have been exonerated, and the state responsible for their deaths has formally apologised for the “unjustified and unjustifiable” killing of the victims.

But that same state still finds it impossible to call to account those responsible for the deaths of innocent people, and the wilful destruction of the lives of their loved ones and friends.

More than any other action in the Troubles, Bloody Sunday sent a signal to the Catholic/nationalist community that it was in the United Kingdom on sufferance – captives with the spoils of occupation.

The actions of successive Conservative administrations, from Cameron (who made that hollow apology in 2010) onwards, indicate that little of that mindset has changed.

The British government has actively worked to undermine peace and justice because of an obsession with exceptionalism; it aligned itself with the DUP to secure the hardest of hard Brexits; and, by dismissing talk of a border poll, it is refusing to recognise the legitimate aspiration to reunification.

We now know that 15 former soldiers, and a former alleged member of the Official IRA, will not face prosecution for perjury at the Bloody Sunday Inquiry. John Kelly, whose teenage brother Michael was shot dead by the Parachute Regiment, said the decision was “an affront to the rule of law”. Indeed it is.

But what’s new? Successive British governments have put the state’s narrow self-interest ahead of the law. They don’t really care who they traduce – sub-postmasters, asylum seekers, Irish people.

Yet, they have invested the British armed forces with the aura of sanctity.

As well as atrocities in Ireland, in recent years the ‘few bad apples’ excuse has been applied to accusations of war crimes in Iraq, Syria, and Afghanistan. The so-called Legacy Act enshrines denialism in law. It has been drafted specifically to protect British soldiers from justice.

The United Kingdom long ago threw away its credibility in the field of truth and justice. It has made targeted attacks on international courts, tribunals and conventions.

Successive British governments have put the state’s narrow self-interest ahead of the law. They don’t really care who they traduce – sub-postmasters, asylum seekers, Irish people.

It has even been prepared to turn on its own legal system in instances where judges do not deliver findings the government wants. Lawyers have been vilified for trying to protect people’s rights - as the families of Rosemary Nelson and Pat Finucane know only too well, that can have deadly consequences.

Whether an incoming Labour government will be any better is anyone’s guess. As Director of Public Prosecutions, Keir Starmer was a cornerstone of the British establishment’s legal enforcement arm.

The Bloody Sunday victims’ families have signalled they will not give up. While the legal system is loaded against them, the reality is this: their loved ones are innocent; those who killed them will be damned for all time.