We’ve spent a lot of time since April remembering and ‘celebrating’ the signing of the Good Friday Agreement and the referendum campaign leading to its endorsement a few weeks later.

Many of the contributions from key players have focused on what Northern Ireland was like during the previous 25 years. A dark and dangerous place. So dark and so dangerous, there were times when it looked like we’d be tipping into a brutal civil war. Yet somehow – and we may never know what went on in the background to prevent it – we always managed to pull back.

But it’s also worth remembering what it was like in the two months after the election to the first Assembly.

Arson attacks on 10 Catholic churches were attributed to the LVF. A Protestant man, known to be under threat from loyalist paramilitaries, was shot dead. RUC patrols came under fire from both loyalists and dissident republicans. Police foiled a republican attempt to launch a fire-bomb attack in central London. The beating, shooting and killing of a man on the New Lodge Road was, according to the RUC, the work of the PIRA.

The three Quinn brothers were killed in a loyalist arson attack linked to the Drumcree stand-off. Dissidents failed to carry out a mortar bomb attack in Newry. Two Catholic brothers were shot and wounded by loyalists in Derry.

Banbridge was hit by a Real IRA 500lb bomb. Twenty-nine people and two unborn children were killed in Omagh by another 500lb car bomb from the Real IRA.

Republicans opened fire on a police patrol in Lurgan. And two shops and a pub were extensively damaged in Belfast, following fire-bomb attacks on three shops in Portadown.

Read more:Alex Kane: I don't care if I'm not the 'right sort' of unionist

Read more:Is the Conservative Party facing the same challenges as the UUP?

Read more:Alex Kane: Is there such a thing as a British identity?

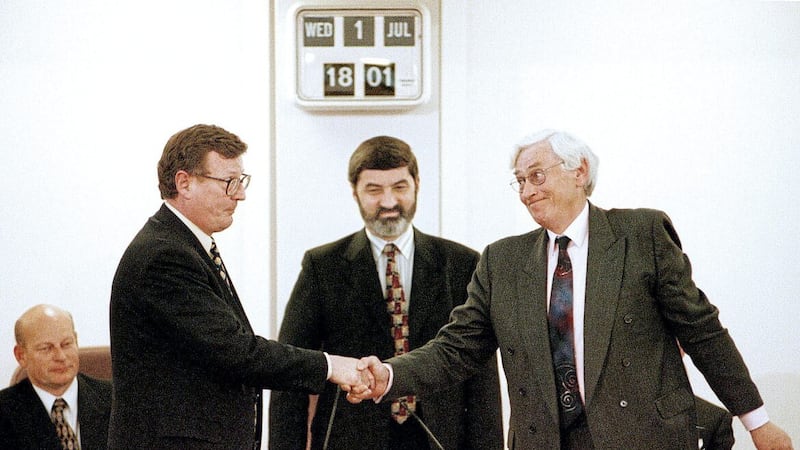

That’s the list – not a complete one, by the way – of attacks and killings in the two months after David Trimble and Seamus Mallon were elected First and Deputy First Minister on July 1 1998.

It was to be another 18 months before an executive was appointed and even that one managed just a few weeks before collapse: and, apart from a few stops and starts, it wouldn’t be until May 2007 that something resembling executive/assembly stability emerged. That lasted until December 2016, since when the executive has been down more often than it has been in business.

It took a long, long time to reach that moment of relative stability in May 2007. And there were many moments from July 1998 onwards when it looked like the total collapse – rather than just the mothballing of the assembly – was inevitable. As far back as 2005 I was beginning to sound warnings about the long-term survival of the political/electoral institutions, even during those periods when the show was on the road again.

The DUP blamed SF and SF blamed the DUP for the assorted stand-offs and suspensions, but both continued to consolidate and maximise support within their respective communities, while the self-styled middle-ground failed to achieve the breakthrough required to challenge the increasingly obvious us-and-them preferences of a substantial electoral majority.

Where we are now is where we have been on so many occasions since July 1998. Indeed, we’ve been in this spot many, many times since March 1972, when the NI Parliament was prorogued.

Yet even though we have been in this spot so often before there is precious little evidence that any lessons have been learned.

Maybe we don’t like learning lessons, because that usually involves a recognition of joint blame and a willingness to accept joint responsibility.

Or maybe we don’t want to learn lessons because that would also mean working on something that could be described as a joint approach to governing Northern Ireland.

That concept was certainly a possibility in 1998, but the possibility has now gone. And it won’t be coming back. Which creates an additional problem, of course, namely that the next repair job – due in September – will, like its predecessor in January 2020, fail the political equivalent of an MOT (assuming, of course, the political equivalent of an MOT centre will actually be available for bookings, unlike the normal centres).

I keep trying to find routes back to something, anything in fact, which could be defined as political stability. But I just don’t see it. I’ve actually no idea how we get to that safe spot in which executive parties manage to govern together in the common interest.

I wouldn’t go as far as saying that SF and the DUP hate each other, but nor is there a single scrap of evidence to encourage the view that they have enough common interest in each other to work together in the broader common interest of Northern Ireland or the north (choose your own preference).

One crucial difference between now and April-July 1 1998 is the absence of optimism. There was a general acceptance that something incredibly significant had happened during those three months, with the accompanying sense of the possibility of circumstances emerging which would allow political business to be done differently and better.

There was also a sense – even with some pretty brutal evidence to the contrary – that paramilitary campaigns on both sides had run their course. Plus, while most knew that the path wouldn’t be easy, nor the final result perfect, there was still a belief we’d be in a better place by 2023.

But, as I say, the optimism has gone. The place we’ve reached is certainly different, but most of us would be hard pushed to say it’s better, in the sense of cooperation and community relationships.

And with hardening evidence of restlessness on the paramilitary fringes and the accompanying rise in the ‘threat level’ who, now, could rule out the intervention of violence from both sides at some point.

Lengthy periods of political instability and lack of governance fuel a narrative of despondency and ‘this will never work’ disconnection from the political/peace processes.

All politicians and people of goodwill need to accept one brutally simple reality: there won’t always be someone or something strong enough or invested enough to stop us toppling over the edge. And that edge is pretty damn close right now.