A friend and I had been talking about Michael Viney, the Irish Times journalist and natural history writer, in the office the other day.

We share a love of his writing and his drawing with thousands of others; we missed him in the paper.

Where had he gone?

And then, news of his passing came and I wrote to my fellow Viney fan to say: "He's gone."

I wanted to headline my message "Death of a Naturalist", I told him.

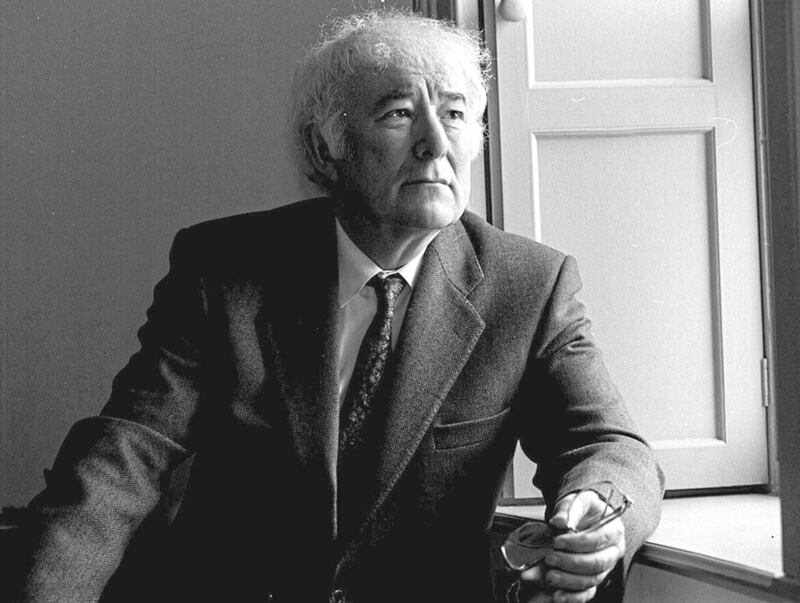

When I think of Viney, I think too of Seamus Heaney and remember that first edition of Death of a Naturalist with the faded pink and greenish cover that my mother bought in the long long ago.

Our English teacher introduced us to Heaney's poetry – he was a fellow St Columb's College man – in the very early 1970s, when he wasn't Famous Seamus and was not on the syllabus.

In the same way that Heaney took our world and named in love the tin scoop for the flour, the wet mud of the sheugh – a rowan like a lip-sticked girl; Viney – an Englishman – taught us native Irish about the beauty around us.

Think too of Patrick Kavanagh and his beloved black hills of Shancoduff.

The sleety winds fondle the rushy beards of Shancoduff

While the cattle-drovers sheltering in the Featherna Bush

Look up and say: "Who owns them hungry hills

That the water-hen and snipe must have forsaken?"

Viney's choices in life were brave ones.

He was a refugee from Fleet Street via a childhood lived in a flat above a fish and chip shop.

In 1962, he wrote his first article for the Irish Times about taking time out from his job at the Evening Standard to live in a cottage in Connemara.

"I'm going to write and I'm going to see if I'm a painter," he said. "I'll supplement my larder by fishing... I can cook anyway... I'll be a different person in a year's time."

In 1977, he and his wife Ethna and their daughter Michele moved to Thallabawn to live as self sufficiently as they could.

He bought a cottage and was gazumped, then upped his bid. That took a bit of bravery.

He threw up a £1,500 a year job for a cottage on £6 a week, an article in the Evening Standard reported on that first flight from Fleet Street.

His Irish Times column, Another Life, chronicled this brave new world.

It could not have been without its challenges – this was no sitcom 'Good Life'.

In that first column, he wrote that he was not retiring or opting out… this life was far from simple.

But his last line was both magical and intriguing... "Next week, I'll introduce the bees."

A deep vein of love for people, nature and Ireland ran through his writing.

In those early days, he wrote that the people of Connemara found him and led him off to build a dry stone wall.

So he may not been much use in the bog – mourners at his memorial service heard he wasn't a great hand at the turf cutting when he started but he became "the man in the cottage".

"While I had no illusions about the 'dignity' of rural poverty or the 'innocence of remote communities', it took the dole-day boozers and the gossips watchful as hooded crows to shake me into a more sensible affection," he wrote.

And as he wrote and lived and charted this natural world, people wrote back, stopped him in the street, showed him the delicate shards of a strange bird's egg or the bones of a fish.

The treasure shared and the illustrations on the broadsheet page down the years – swallows soaring over a church steeple; mating frogs – brought back memories of our old nature table in primary school.

There you might find the iridescent feather of a magpie, a glob of frogspawn in a jam jar, a wasps' nest crinkly as antique tin foil.

What Heaney and Viney and Kavanagh inspire in us is a love of our natural world... the curlew and the heron; the butter yellow gorse.

For me, such a love has come slow and late – it's in the blackbird's song; the delicate lace of cow parsley; the softness of a summer's evening.

So farewell Michael Viney – standing with a twinkle in your eye beside the scarlet fuchsia dripping in the rain and the dry stone wall – we're all the wiser for reading you.