The guidelines for naming a planet’s surface features are not inclusive enough and are biased towards men, an academic has said, as research shows fewer than 2% of Mars’s craters are named after women.

An analysis of the International Astronomical Union’s (IAU) database has also revealed that only 32 (2%) out of 1,578 known Moon craters bear a woman’s name.

Planetary features are distinctive characteristics or elements present on the surface of, or within, the planet.

Alongside craters, they also include mountains, valleys, canyons, volcanoes, oceans, deserts and many more.

In an open letter published in the journal Nature Astronomy, Annie Lennox, a doctoral researcher at The Open University, said the male-biased culture of naming planetary features “inherently disadvantages women and marginalised groups”.

She is urging the IAU – an international association of professional astronomers – to change its policies which are “biased towards cis (cisgender) white men”.

Ms Lennox, from Aberdeenshire, said: “Space exploration has revealed worlds of rock, of ice and… metal.

“For all the worlds in our solar system, it has become customary to name prominent surface features such as craters.

“Distant craters on the Moon, Mars and Mercury record a history much closer to home: celebrating the achievements of mankind, and to a much lesser extent womankind.”

Italian astronomer Giovanni Battista Riccioli first started naming lunar craters in 1635, adopting the names of famous scientists for his discoveries – a convention still maintained by the IAU today, Ms Lennox said.

While the IAU does not bestow the names itself, it does help establish working groups or task forces to propose and approve names for specific features based on certain guidelines – often honouring historical figures or mythology or cultural themes.

Ms Lennox said IAU’s guidelines have an impact on the diversity and inclusivity for the scientific communities that ultimately choose the names.

She said: “Surface features are named following conventions that are set and maintained by the IAU.

“Frustratingly, elements of the current conventions crystallise historic injustices and contribute to a lack of diversity within the nomenclature.

“This is an example of how systemic underrepresentation and undervaluation of women and marginalised groups manifests in today’s scientific systems.”

Her research found Mercury to fare slightly better than Moon and Mars in women’s representations – with 49 out of 415 (11.8%) craters bearing a female name.

Ms Lennox believes this is because Mercury is a more recently explored planet compared to some of the others in the solar system and may have benefited from the increase in the number of women working in science, technology, engineering and mathematics.

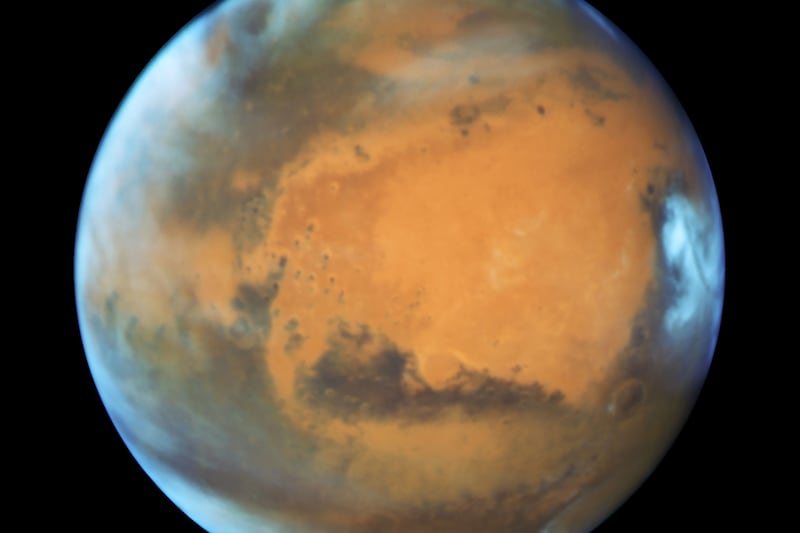

Mars comes out the worst, with just five of the 280 (1.8%) craters named after women.

Meanwhile, all crater names in Venus have a female origin but Ms Lennox said that only 38% “are named after actual women who made real contributions to society”.

She said: “On the one planet intended to exclusively celebrate the contributions of women, more features have been given meaningless, arbitrary female first names or the names of mythological goddesses than those of real women.

“The crux of this argument is that weighting celebrity status – placing an emphasis on recognition and essentially prioritising fame over contribution – inherently disadvantages women and marginalised groups regardless of the field.”

Ms Lennox said that researching names of craters across planets has been her starting point but she is now working with teams around the world to analyse every named feature in the solar system.

She said: “I myself have named some craters.

“I knew I wanted to name my discoveries after women as I could sense a dearth of women represented in the area I was studying, despite statistics on this not being readily available.

“That realisation really prompted this whole project.”