Cold Case Collins, RTÉ One, Wednesday and RTÉ Player

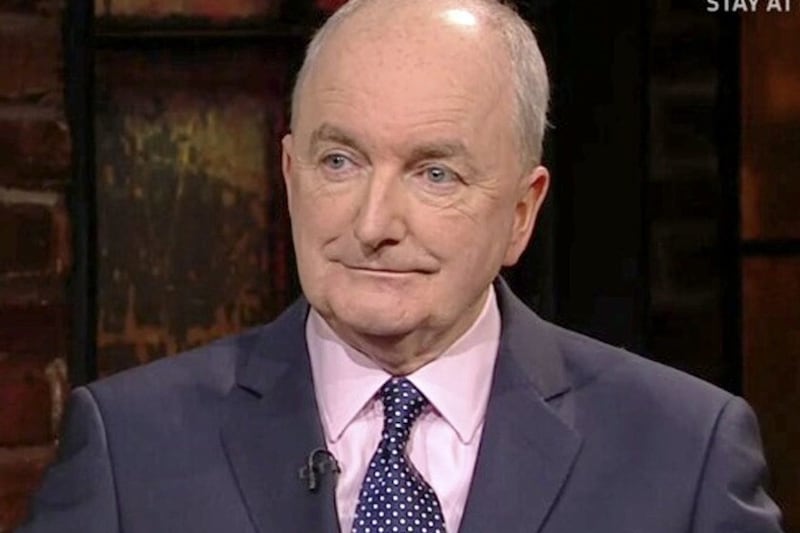

MARIE Cassidy had it from the outset.

As a former state pathologist, she was less interested in the noise surrounding the death of Michael Collins at Béal na Bláth and more focused on the scientific facts.

“This happened there, he was shot, end of… move on,” she said with a cheeky grin near the beginning of this feature-length exploration of his death.

But she knew there was more to it than that and off we went on a 100-minute journey that effectively brought us back to the same starting point.

Cold Case Collins was a curious thing.

A dramatised version of a fictional police investigation into Collins’s shooting 100 years ago this week, it was interspersed with an expert panel discussion on the known facts around the event and theorising on the shot that killed him.

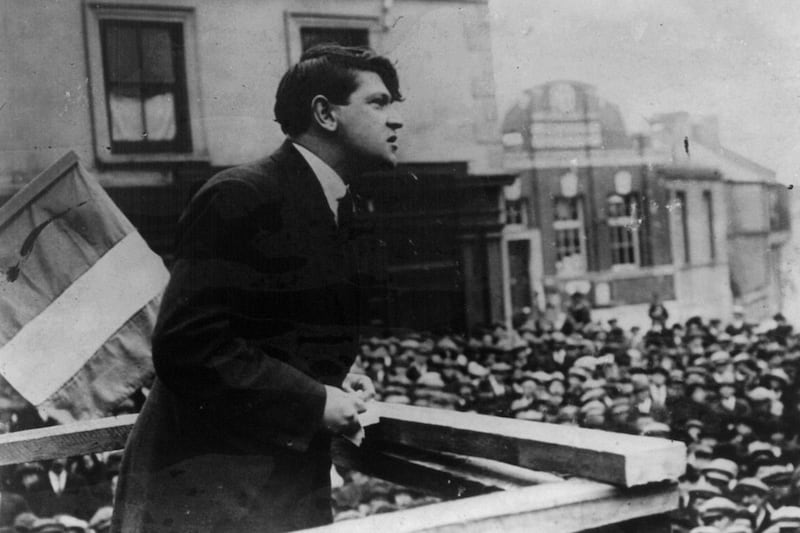

The Minister for Finance and Commander-in-Chief of the National Army, Collins was shot dead when his convoy was ambushed by anti-treaty forces in west Cork, one month into the civil war.

Collins may have been in the rebel-held area to see if there was any prospect of peace talks or he may have been taking the opportunity to demonstrate physically that the writ of the Free State government ran through all parts of the 26 counties. He may also, of course, have been trying to do both at the same time.

Protected by a bodyguard of 24 men, he was the only one killed when his convoy drove through the ambush site at dusk.

The group of 30 to 40 irregulars waiting for him had mostly dispersed, believing he wasn’t coming, and something less than 10 remained to confront him.

Collins seems to have been his own worst enemy. Rather than seeking safety in the armoured car in the convoy, he ran along the road firing at the rebels as they appeared to flee the area.

His actions were described as “arrogant and impulsive” by one of the expert panel members. Retired Lt Col Dan Harvey also pointed out that Collins had no formal military experience.

The account of the fictional police investigation a couple of years after the killing was convincingly done but hardly realistic. Two members of the newly-formed Garda Síochana questioned all interested parties, including Major General Emmet Dalton and Dev himself.

Dev (who got the blame in the seminal dramatisation, the eponymous movie by Neil Jordan) refuses to accept or deny that he knew Collins’s convoy was to be ambushed.

The most interesting section of Cold Case Collins was the last 30 minutes, when the panel inspected the military cap Collins was wearing and his death mask.

It seems most likely that it was an unaimed shot which stuck him, around the hairline, above the ear. The panel concluded that it was fired from a rifle (likely a standard British army issue Lee-Enfield 303) and while the entry wound was tiny, it left a large exit wound in the back of his head.

Dr Cassidy concluded that Collins was unlikely to have been able to speak before his death, despite the many phrases attributed to him, including: “Forgive them, bury me in Glasnevin with the boys.”

She also dismissed the conspiracy theory that Collins was shot by a British agent in his own party (Dalton, according to some), whom, it was said, took advantage of the ambush to shoot him in the back of the head.

Although an interesting and engaging hour and a half, we ended up where we started. There was no mystery. Collins was shot in a civil war ambush by anti-treaty forces.

“This happened there, he was shot, end of … move on.”