Plans to ban anyone born in or after 2009 from legally buying cigarettes easily passed their first hurdle in parliament this week. Championed by PM Rishi Sunak, it’s likely to be his sole positive legacy. Boris Johnson and Liz Truss opposed the measure even though smoking kills 8 million people each year including 1.3 million non-smokers exposed to second-hand smoke.

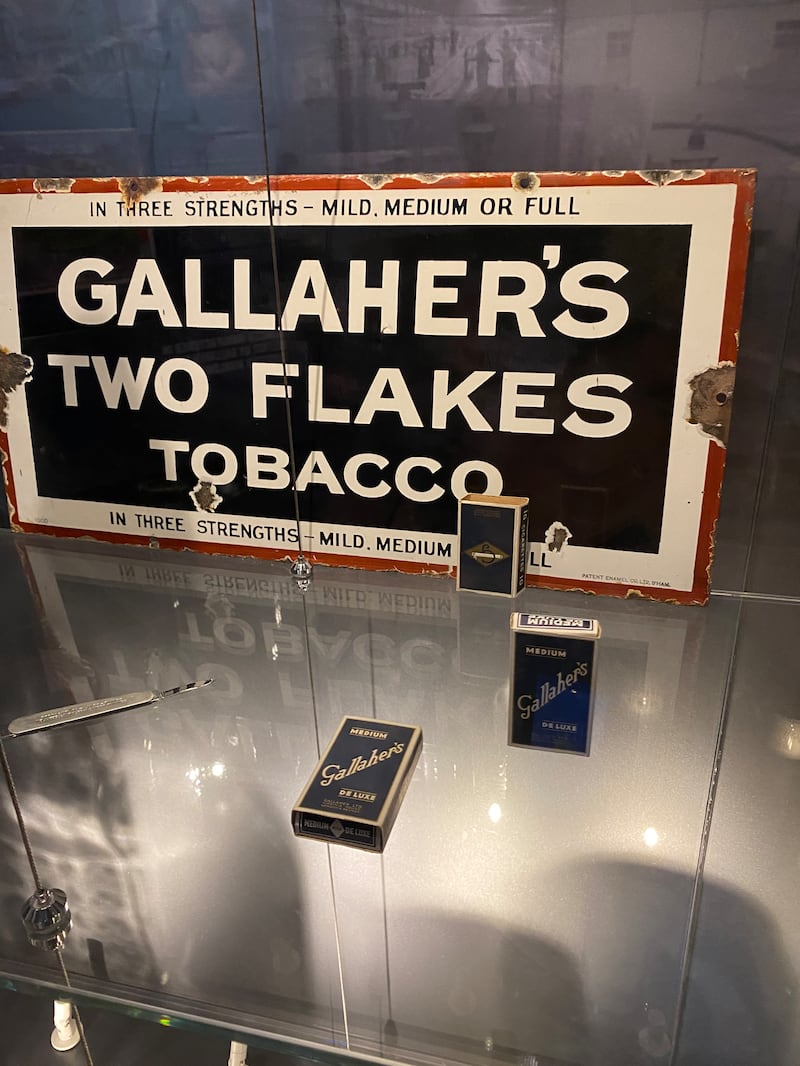

As a boy, I grew up beside the largest cigarette factory in the world, Gallaher’s, on York Street in north Belfast. On hot summer days, the sweet smell of raw tobacco filled the air as hundreds of workers transformed the tobacco leaves into one of the company’s most famous brands ‘Gallaher’s Deluxe’, better known as ‘Gallaher’s blues’.

I realised I’d reached a milestone when I came across something from my childhood exhibited in a museum. This happened on a visit to Titanic Belfast, where artifacts from the era are displayed and in one of the cabinets, I noticed an exhibit of Gallaher’s cigarettes.

This struck a chord as they were my father’s preferred brand. I seem to remember they came in three strengths, with my father preferring the strongest available, even though their nickname was ‘coffin nails’.

My late Dad was such a prodigious smoker he would have needed a chimney on the top of his head. I remember his habit of lighting multiple cigarettes which he positioned behind his bar as he served customers. As a child, I was amazed at his ability to keep them all alight as he walked up and down, pulling pints and serving whiskey.

My job as a nine-year-old was washing glasses and, as the night progressed, I marvelled at the foot-deep blue cloud which gathered beneath the bar’s ceiling as dozens of men chain-smoked pipes and cigarettes.

Eventually, when it felt like all oxygen had been depleted, someone would open small sash windows, allowing the toxic fumes to be sucked out into the night. I’m convinced if a fire engine had happened to pass when this occurred, they’d have stormed in with fire extinguishers.

My job as a nine-year-old was washing glasses and, as the night progressed, I marvelled at the foot-deep blue cloud which gathered beneath the bar’s ceiling as dozens of men chain-smoked pipes and cigarettes

From a young age, I was aware of the dangers of smoking, having spent the first few weeks of my life in a ventilator due to my mother’s smoking. No blame can be apportioned as it was 1961, a time when television advertisements even lauded the health benefits of smoking. The conclusive link between smoking and cancer had yet to be made so almost everyone smoked - even the local GP’s desk sported an ashtray.

Growing up in the 1960s and 1970s, smoking was ubiquitous and family car journeys felt like a form of involuntary fumigation. I’m certain if measured I’d have been on 10-a-day simply due to passive smoking.

- ‘Wearing casual clothes at funerals remains a peculiarly Catholic phenomena - I’ve yet to see anyone wearing a soccer top at any Protestant funerals’ - Jake O’KaneOpens in new window

- What has Tribeca ever done for Belfast? - Jake O’KaneOpens in new window

- I can see clearly now, thanks to my cataracts - Jake O’KaneOpens in new window

My father eventually stopped after his heart stopped, twice; the fact that it took a second heart attack before he quit proves the power of smoking. I never took up the habit, with habit being the proper term as it was discovered nicotine was every bit as addictive as opioids, heroin or cocaine.

Growing up in a working-class area, smoking was viewed as a rite of passage from adolescence to adulthood - you went from short trousers to a single fag on the bus to school. Even after decades of scientific proof regarding its terminal effects, smoking continues to persist.

I had a glimpse of how difficult it is to deter a hardened smoker whilst standing behind an elderly lady in a shop queue.

This occurred soon after a new government anti-smoking scheme which saw graphic photographs of the dangers of smoking put on cigarette packets. No punches were pulled, with horrific images of everything from gaping cancerous mouths devoid of teeth to human feet with toes amputated.

On the day in question, the lady in front of me asked for a particular brand of cigarette. Having been served them she dismissively tossed them back across the shop counter saying, “Awk no son, I want the packet with the photograph of the missin’ toes, not the missin’ teeth. Ya see, I’ve still got lovely teeth and at my age I don’t give a toss if I lose a couple of toes.”

As he handed over what she had requested, the lady told the bewildered shop owner, who was trying his best not to laugh, that she’d been smoking longer than he’d been alive. No doubt she was also married to that mythical 100-year-old man who had smoked and drank every day of his life yet was never a day sick.