AMIDST the daily diet of budget cuts and impact assessments on the vulnerable, the question of whether Northern Ireland is under or over-funded is a contested one. For some it seems the economy is currently on the equivalent of “special measures”.

The recent submission of the NI Fiscal Council (NIFC) to the NI Affairs Committee is a helpful contribution with echoes for me of the biblical picture of Pharoah’s dreams and seven years of abundance followed by seven years of famine in Egypt (Genesis 41). As then, when the lean years come it seems the period of plenty is soon forgotten. Unlike then, it seems preparations for tougher times have not been made.

That Northern Ireland requires higher public spending per head to deliver the same quantity of services as England is not contested – using deprivation, demographic and cost indicators to estimate relative “need”, the NIFC concludes … “The analysis set out indicates that the block grant per head in Northern Ireland is around 25 per cent higher than UK Government spending in 2023-24. This is broadly in line with the relative need for public spending, which we have estimated to be 124 per cent.”

In other words, the so-called “Barnett squeeze” is less about today (although elevated inflation and higher public sector wage deals in England do pose particular challenges) and more about tomorrow when the “funding premium” is projected to fall below 20 per cent (early 2030s) and 10 per cent (late 2040s). Surely a wake-up call for radical thinking on public service provision and funding?

The “Barnett formula” and “squeeze” are not well understood – the “squeeze” does not necessarily mean less cash – paradoxically, the more cash we receive the greater the convergence with England, precisely what the formula was purposed to achieve. The funding premium averaged 55 per cent in the 1980s, 38 per cent in the 1990s, 31 per cent in the 2000s and 25 per cent in the 2010s.

However, as recently as 2018-19, the premium was as high as 40 per cent, aided by some additional non-Barnett funding. It was not uncommon to see departments scurrying in spring each year to spend money on a “use it or lose it” basis while it was reported recently that £461 million in unspent funding has been returned to HM Treasury since 2016 due to the lack of suitable capital projects.

While the value-for-money, programme evaluation and effectiveness of some Northern Ireland spending allocations require closer scrutiny (note Lyons Review and various NIAO reports) the updated estimates of “need” might also imply that the estimated £800m budget shortfall this year – a gap unlikely to be closed significantly in-year - is as much a reflection of a revenue deficit. Maintaining so-called “super parity” has come at a cost, namely the declining quantity and quality of public services.

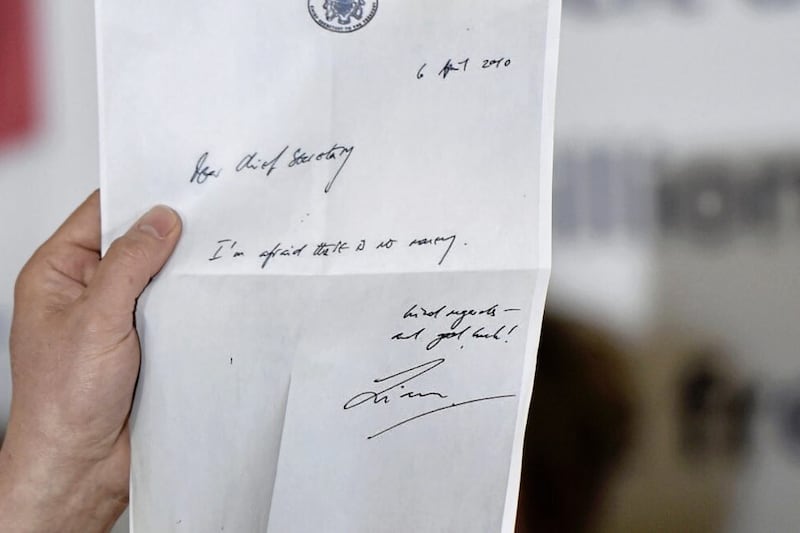

As we contemplate the possible return of Stormont institutions and potentially another financial package, it is worth reflecting that previous additional, “one-off” funding - St Andrews (2006), Hillsborough Castle (2010), Fresh Start (2015), Confidence and Supply Arrangement (2017) and New Decade, New Approach (2020), appears to have been used primarily as “top ups” rather than an enabler of strategic change and reform (health). Without these additional packages, the fiscal reckoning would have come earlier; the adjustment now is much steeper.

There is a wider context and some uncomfortable truths in current local difficulties. The UK Exchequer has been buffeted by “shocks” in the last 15 years that have left economic and fiscal scars. Macro-wise, the UK appears ex-growth with public finances more fragile - public debt to GDP is now perilously close to 100 per cent. The interest payable on debt soared to £107bn in 2022-23 while the tax burden is already high and rising – soon, one in five will be paying tax in the 40 per cent band.

Long-term pressures on public finances from weaker labour force participation, ageing demographics and net zero transition all suggest HMT will be less receptive going forward. Every £1bn is more precious.

The immediate task of any incoming NI Executive will be to stabilise the public finances and the NIFC offers a range of options including efficiency savings, increasing regional rates and fees, explicit water charges and seeking additional fiscal powers.

However, surely now is the time for a more fundamental rethink on what we expect from government, what is affordable, what should we pay more for ourselves and who should pay? Of necessity, the pandemic resulted in even “bigger government” and raised even greater and some unrealistic expectations of what can be delivered (and in a place with deep-rooted Keynesian-type views on spending and weak productivity).

In 1942, the Beveridge Report set the foundations for the welfare state and the post-war agenda of Atlee’s Labour government identifying the so-called five “giant evils” to eradicate - want, disease, ignorance, squalor and idleness. We use different terms today, but these areas still absorb the bulk of public expenditure. Our challenge is not unique. The Economist recently referred to governments “living in a fiscal fantasyland” with higher debt costs amplifying the strains in the years ahead, reviving calls for a zero-based budgeting approach and other more radical action such as Ireland’s An Bord Snip Nua in 2009.

Out of present difficulties comes an opportunity to reframe the next decades, but there will be pain, hard choices and trade-offs. Bad politics invariably equates to bad economics. The cost of not confronting uncomfortable truths and “sacred cows” is, as presently with health, change still happens but in an unplanned and disorderly fashion.

The biblical story had a happy ending . . . a family reunited and reconciled with an estranged brother – but only after confronting some hard realities. Presently, we are not in a dream, but for some it must seem like a nightmare.

:: Alan Bridle is UK economist at Bank of Ireland UK