KEVIN Barry (1902-1920) has become synonymous with Irish republican sacrifice. A hundred years after his death, images of him, particularly in his hooped Belvedere College sports shirt, are still instantly recognisable. He appears on the 2020 Sinn Féin calendar.

Kevin’s dynamic eldest sister Kathy (Kitby) Barry Moloney (1896-1969) was my grandmother. She spoke constantly of Kevin to me and my siblings, her only grandchildren.

Yet she never even mentioned her husband Jim’s brother Captain Paddy Moloney (1900-21), killed by RIC in a fight outside Tipperary town in May 1921, or her father-in-law PJ Moloney TD, or the significant Civil War roles and sufferings from wounds and on hunger strike of her husband Jim and his brother Con as senior officers on Liam Lynch’s anti-Treaty IRA staff.

Nor did she say anything much about her own important role as general secretary of the Irish Republican Prisoners’ Dependents’ Fund from 1922 to 1924, and as de Valera’s personal emissary to Liam Lynch. She never so much as alluded to her son-in-law’s Halpenny and Rice parents from Co Down, republican exiles from the new northern state. Kevin, and Kevin alone, was who mattered for posterity.

I found out about the experiences and hardships of my other revolutionary relatives, and of my grandmother’s own significant roles, long after her death. Beware any one person who assumes the role of exclusive custodian of family memory.

When Kevin was awaiting death, and immediately after his execution, those iconic photographs, and his status as a ‘medical student’, were carried on newspapers across the world. He looks what he was: a healthy, confident boy, his sports jersey suggesting a team player and all-rounder rather than a neurotic loner.

We now know that he was indeed well-rounded, athletic, good-humoured, purposeful, and an observant Catholic. But he was also fond of drink, was habitually irreverent towards authority, and always had an eye for girls.

Unusually for Irishmen of his era – and have we changed all that much in the succeeding century? – he was also very comfortable in female company.

The camera did not lie, but it did mislead. ‘Poor little Kevin Barry’, as described by the republican priest Fr Albert, Kevin most definitely was not. The photographs through which he is still commemorated were all taken when he was aged 15, 16 or 17, not when he was captured in September 1920 about 10 weeks shy of his 19th birthday and at the end of his first year in university.

What self-respecting student nowadays who had completed first year of university would accept classification as anything other than ‘adult’? Many of those urging a reprieve stressed his ‘extreme youth’, and argued that he had been coerced by older men.

But in truth Kevin was himself a man, a volunteer of three years' standing, with unusually extensive operational experience in Carlow and in Dublin. Like his older brother Michael, who ran the farm in Carlow upon which his widowed mother and six siblings depended, Kevin took an early and clear decision to fight and if necessary to die for his cause, joining

the Irish Volunteers in 1917.

A commemorative ballad beginning ‘In Mountjoy jail/ One Monday morning’, first heard within weeks of his death, is still widely sung inside and outside Ireland, and not only by contemporary Irish republicans and among the Irish diaspora. By the 1960s it had also become part of the repertoire of the international folk music movement with its themes of

universal struggles against injustice and oppression: the great African-American radical Paul Robeson, Pete Seeger, and Leonard Cohen have recorded the song, along with lesser lights including Glaswegian Lonnie Donegan.

The Swedish musician Bjorn Ulvaeus released a version with the Hootenanny Singers in 1964, before wisely abandoning them for rather more comely colleagues in the group Abba.

In much the way as It’s A Long Way To Tipperary and Lili Marlene were respectively adopted by German and British troops, I have also heard the song sung by former British soldiers and RUC officers. This is partly because it has a simple, catchy melody. But it is also because Kevin’s story, of someone very young in years yet resolute in commitment to his cause, whatever the risks and whatever the cost, resonates beyond the particulars of the Irish War of Independence.

The conjoined names Kevin Barry pass down the generations, alongside Pearse, Emmet, and Plunkett, particularly in the Irish diaspora and within northern republican communities. Kevin Barry Curran, the former leader of Britain’s General and Municipal Workers Union, told me that in the 1970s his name sometimes complicated his work with Scottish trade unionists. During the Troubles, men carrying his name sometimes found the headlines.

One example is Kevin Barry O’Donnell, a very active IRA Volunteer who although only 21 had twice been acquitted on weapons charges before meeting his end in an ambush by British special forces following an ill-conceived IRA stunt in Coalisland, Co Tyrone.

Our Kevin Barry also died as the result of a botched operation, the aim of which was to rush and disarm troops sitting cramped and supine in the back of a lorry collecting bread from a bakery.

IRA accounts of what happened differ: the man in command blamed an unnamed overexcited subordinate for needlessly opening fire, whereas another participant gave a contradictory account. In any case, Kevin was captured sheltering under the lorry, where he had hidden in order to clear a blockage in his gun (he told his sister, my grandmother Kathy Barry Moloney, that he had killed a soldier before his automatic jammed for a second time).

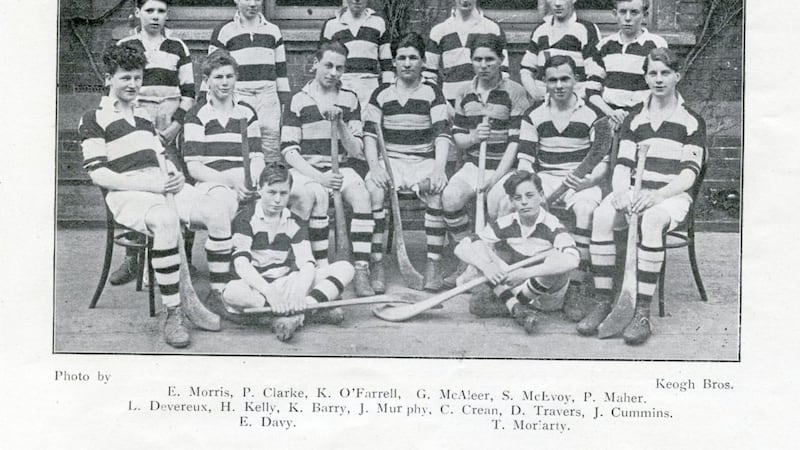

Unlike most young volunteers from Carlow and Dublin, during his short life Kevin had some knowledge of the Ulster counties. This was because his closest friend in Belvedere College, and later in UCD Medicine, was Gerry McAleer, whose family ran the Commercial Hotel in Dungannon, Co Tyrone. Kevin stayed there in the spring of 1918, writing to his sister of how kind everyone was: “The longer I stay, the better I like it”.

Despite the intensity of political divisions in the county, Tyrone was not to be a republican hotbed between 1919 and 1921: in fact, my study of The Dead of the Irish Revolution shows that when deaths arising from political violence are measured by population, it was the most peaceable of the 32 counties, quieter even than Cavan, Fermanagh, Down, Donegal and Wicklow.

Carlow, Leinster’s smallest county, ranks as high as 14th in terms of fatalities when measured by population, while Cork is by far the most violent.

In June 1921 Tyrone’s Gerry McAleer was arrested and interned while helping out on the Barry farm in Carlow. Released following the Truce, after qualification he went to Britain.

Fate drew him into the Royal Air Force, where he became a senior officer, retiring as an Air Commodore in charge of medical services in the Far East. In 1957 he was even appointed

an honorary medical adviser to Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth. Despite their vehement republicanism, the Barry family remained in very close touch with him.

One wonders whether, if called upon to inoculate Her Majesty before some foreign trip, he was ever tempted to use a needle a shade thicker than strictly necessary.

Eunan O’Halpin is Professor (Emeritus) of Contemporary Irish History at Trinity College Dublin. He has just published Kevin Barry: An Irish Rebel in Life and Death (Merrion Press, £15.95) and (with Daithí Ó Corráin), The Dead of the Irish Revolution (Yale University Press, £50)