“Boke was very deliberate,” says author and artist Oliver Jeffers.

He's referring to his use of the word, a Northern Irish favourite, in one of his children's books, The Incredible Book Eating Boy.

Henry eats books, lots and lots of them. He gets a sore stomach. He bokes.

"American parents will come up to me and say: 'thanks for adding 'boke' to my child's vocabulary'," Jeffers laughs.

The 39-year-old is back in Belfast for a holiday from his adopted home New York. He's given up a bit of family time to talk to The Irish News about his growing acclaim in the fine art world and his parallel and somewhat accidental career in making children's books.

Jeffers is probably best known for his children's books. His debut, How to Catch a Star, was published in 2004 to floods of acclaim, sales and awards. The Incredible Book Eating Boy went on to win the Irish children’s book award. The Day the Crayons Quit was a New York Times bestseller. He has written and illustrated 14 picture books, collaborated on another four picture books, and illustrated seven young adult fiction books.

His 'grown-up' work has also really begun to gain traction. This comes as a relief for Jeffers who felt at times his painting was sometimes being dismissed within the fine art world because he also made children's book.

"Fifthteen to 20 years ago, when I was starting out, the art world was much more conservative in its perceptions of illustrated art, and I found it difficult to break through given the extent of the visibility of my picture books. Things have changed a lot in the past two decades. Much of it comes down to how picture books are enjoying a surge in popularity and fashionability, but also art world attitudes have changed and have become more inclusive of ‘outsider’ art.

"Nowadays the balance is good. I am respected in the art world despite the fact that I do picture books and I am respected in publishing industry and they seem to enjoy that I have a toe in this other world."

There is an unavoidable energy about Jeffers. Not a nervous energy. On the contrary, he sits calmly and is confident in his opinions.

But he is one of those people that ups the ante when it comes to pace of life.

His motivation is, in his own words, “because I can, I should”.

Jeffers was the second of four boys born into a north Belfast family.

"A lovely childhood, three brothers. A big family and lots of friends," was it in a nutshell says Jeffers.

He wasn’t born with a pencil in his hand, so to speak.

“I think I was more interested in climbing trees, digging holes, football in primary school and the early part of secondary. Then when I realised I could get out of class because I was good at art and they needed me to design the school play set or something like that then I definitely started enjoying it a lot more."

He went to Hazelwood Integrated in Newtownabbey, where he thrived.

His Upper Sixth school report talked about a pupil with "strong opinions" but with an "open mind". His art and design teacher said he "has the skill and enthusiasm to suceed in this area of study."

Jeffers believes strongly in the benefits of integrated education and a proponent of it worldwide.

“[Hazelwood] was the beginning of my eyes being opened up, the broadness of the planet and the variety of people that live here and elsewhere. We were lumped into a class with 30 other kids. It didn't occur to any of us at that age to ask what religion the other was."

“It was after a few years before people started to figure things out and then you didn't care because that is your pal. Where he goes and hangs out at the weekend is probably very different to where you go and hang out at the weekend but he is just like you in every other way.”

Jeffers was raised a Catholic but encouraged by his parents to explore the teachings of other religions and to question everything. He's now a devout atheist.

It was in 1995 when he came runner-up in The Irish News amateur art competition in 1995, that he seriously considered painting as a direction in which to take his life.

During a year out from studying Illustration and Visual Communication at Ulster University (from which he graduated with a First Class Honours Degree) he began to sketch a series of pictures while travelling across Australia and America that would become the illustrations of his first book How to Catch A Star .

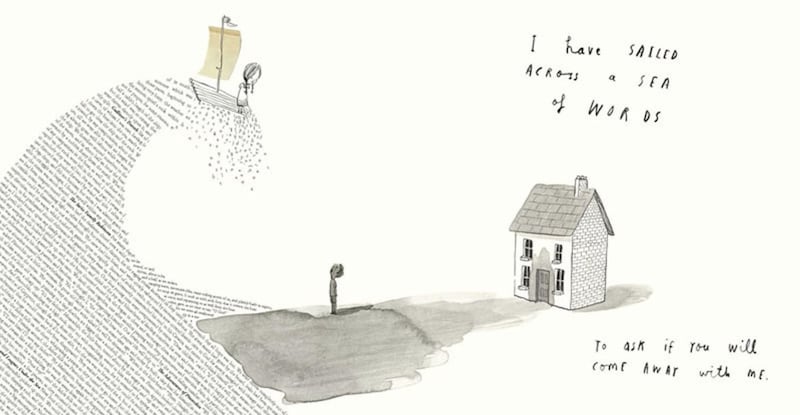

His books are recognisable by their quirky illustrations and trademark awkward-lookinghandwritten type - almost like that of a child trying their very best to stay on the line. Like all good children's books, parents seem to be just as big fans of Jeffers’ work as their children.

A local humour and hint of the surreal are shared themes to draw from his books and paintings.

"The books and paintings come from the same place, from this willingness to create... Each one is born because I want to make it happen. But the way in which I differentiate it when I am talking to art college students is the books are more like telling stories and the paintings more about asking questions."

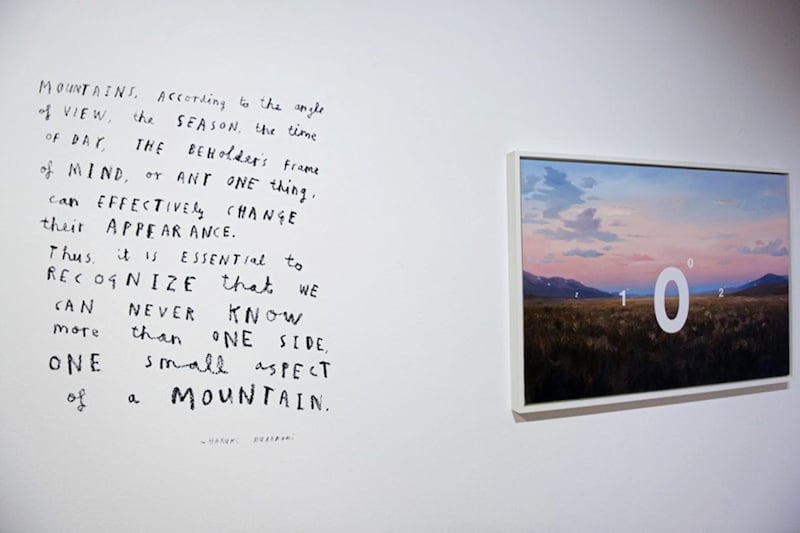

One of his grown-up projects is his landscapes and seascapes series.

Using his trademark handwriting he paints numbers on top of the canvas of bold sea or land imagery, presenting the viewer with an expression of art and science.

On the landscapes, the numbers are angles showing the exact incline on parts of the landscape.

On the seascapes each number is intended to show the depth of the sea at that point using fathoms, a now redundant and largely inaccurate system for measuring depth.

Rather than increase our understanding, this combination makes things less clear.

On the landscapes it provides a distraction.

On his seascapes the fathoms are a comment on the limits of human capacity for understanding. The surface of the sea is not flat but in constant motion and what lies beneath the surface is notoriously uncharted so to measure it with any accuracy is near impossible.

Jeffers fascination with the sea began as a child taking trips up the north coast. “Seeing a very angry ocean up by Giant's Causeway and Torr Head that definitely has put that into my brain somehow someway,” he admits.

Another ongoing and critically acclaimed project is a series of dipped portraits. Jeffers identifies subjects, interviews them for as long as three hours and paints their portrait. Then, in front of a limited audience connected with that painting, he ceremoniously dips half the image into a bucket of paint so it is lost forever.

That the whole image can only be remembered, not seen, fascinates him.

He hopes to make a film about his dipped paintings experience.

Jeffers has also begun collaborations in product design. He had always fancied making objects that expanded on the characters and worlds of his stories. He didn’t, however, want to sign the design and making of the products over to somebody else.

He started collaborating with friends. The collection, which include toys, jewellery and clothes are ethically manufactured and money is donated to the International Rescue Committee from each sale.

So busy is Jeffers he now has four employees. One is his wife Suzanne, also from Northern Ireland, who is his business manager. They have a one year-old boy. The other three staff manage his publishing, fine art and online store for him.

He continues to post on social media himself. Jeffers cringes but concedes that social media has been crucial in the building of the ‘Oliver Jeffers global brand’.

"I think I have used it to my advantage for sure. I've used it as a microphone rather than a dialogue."

He's also used it to make political points. Jeffers is anti-Trump and anti-Brexit. He is also disgusted at what has been happening in Aleppo.

"If you look at all the things individually it certainly looks as though humanity is headed down a downward spiral whenever people are putting individual greed before the common good....

But he tries to remain optimistic.

“We probably are better off than at any time in history really as a civilisation….I try to tell myself that maybe things aren't as bad as they seem. We aren't headed down the toilet."

During the hour long interview we have covered a lot of ground.

“I have no idea what I just said in that interview. I am only just awake”. One suspects it is little to do with him just rolling out of bed but because he is already thinking about one hundred other things he wants to do. The last hour in the Merchant’s cocktail bar is but a faint memory to Oliver Jeffers. It's onwards and no doubt upwards.

Five Children's books that every child should read.

- Tusk Tusk by David McKee

- The Enemy by Davide Cali and Serge Bloch

- Where the Wild Things Are by Maurice Sendak

- The Bad Tempered Ladybird by Eric Carle

- Clown by Quentin Blake

What do you miss most about Northern Ireland?

- Fish and chips

- Ulster fry

- Veda bread

- Scenery.

- The people. People are just good fun here. Whenever we're not being horrible to each other we are actually some of the nicest people on the planet.