THE Dublin to Belfast road is endless on international nights. The best strategy is to break the drive down into segments.

Dublin to the Drogheda toll bridge; Drogheda to Dundalk; Dundalk to Newry. They’re journeys within a journey. The road between Newry to Belfast is interminably long, particular at one o’clock in the morning.

Last Thursday night, I passed umpteen coaches and flexi-buses carrying Republic of Ireland supporters back home. They probably got out of work early that day and would’ve spent a coin or two before the game, as well as paying for their match tickets for the visit of Georgia in a World Cup qualifier.

I wondered what the mood was like on those buses trundling along the midnight roads. Was it worth it? Stopping work early? Spending those hard-earned euro in the capital?

From an Irish perspective, the performance against Georgia was lamentable - the first-half was arguably the worst I’ve watched in 15 years covering the team.

It had no redeeming features whatsoever, and the second half was only marginally better even if Ireland got the all-important goal that won the game.

Four nights later, the Irish put in a better performance against Moldova in Chisinau. Ireland’s hosts were one of the weakest they’ve played in qualification for some time.

Crusaders or Dundalk, champions of Ireland, north and south, would have beaten the Moldovans. Nevertheless, six points were banked over the two games and the Republic are level on points with Serbia at the top of Group D.

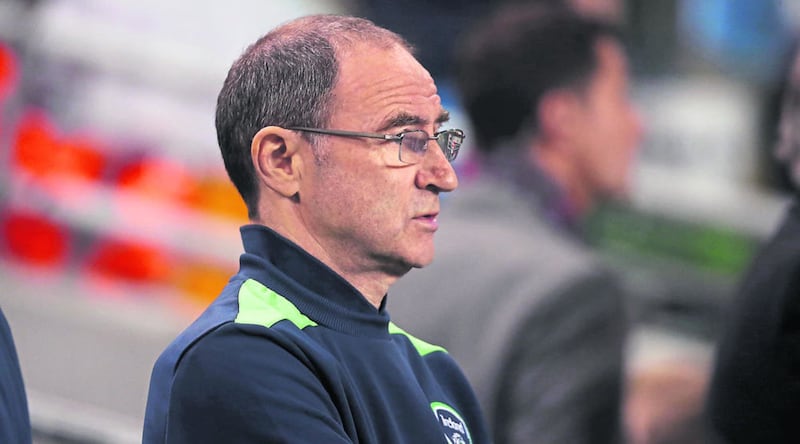

So what’s the problem? Why the dissent? Over the last week in his press briefings, Republic of Ireland manager Martin O’Neill cut a surly figure.

He was tetchy towards any question that was remotely critical of the team’s performance against Serbia in Belgrade and was equally irritable in the lead-up to Ireland’s scruffy 1-0 win over Georgia.

Of course, for a number of reasons international management can be a frustrating job. It doesn’t matter if you’ve the wealth of experience that O’Neill has.

No other level of football is scrutinised and dissected as much as the international game. The games are spread out and therefore every detail gets limitless media coverage, unlike at club level. Tactics are given the fine-tooth comb treatment for days after. Substitutions are studied and debated.

Even the manager’s body language and temper is discussed in depth. And if a player happens to have a bad game, that bad game lasts until the next international window before he can expect to make amends.

O’Neill, a successful club manager for many years, has no time for this kind of detailed, almost nerdish discussion on 90 minutes of football every few months.

The manager and his players do not have the luxury of making amends the following Saturday, as in club football. That’s how international football rolls.

In his newspaper column, ex-Ireland international Stephen Hunt reckoned that O’Neill probably has access to his players for roughly six weeks of the year.

Continuity of selection is difficult to maintain while establishing patterns of play probably more so. But even allowing for the perennial hurdles an international manager is faced with, the manner of the Republic’s performances in the current qualification campaign still fall short of the expected standard, especially after the foundations that were laid during the recent Euro finals in France where, barring the Belgium defeat, a lot of the Irish players expressed themselves.

For large swathes of their games at the Euros, the Irish played through midfield and players took charge of the ball. Speaking ahead of the Georgia game, O’Neill was asked what area of improvement was required after their performance in Serbia in September.

Without hesitation, O’Neill replied: “Ball retention.”

He expanded: “I think the players should feel confident in themselves, have the confidence to deal with the ball. To deal with the ball when you have space is not what I’m talking about; it’s dealing with the ball in tighter situations, which the players are capable of doing.

“But sometimes you go through a 10-minute spell where you’ve maybe given it away needlessly on two or three occasions. And you find it a heck of a job getting the ball back. Now, the pitch was difficult [in Belgrade] but it was difficult for both teams, and there was a spell when we did give it away.”

In the context of the manager’s own analysis, the team’s approach throughout the Georgia game was inexplicable. The team opted for route one football as defenders Stephen Ward, Ciaran Clark and Shane Duffy - not so much Séamus Coleman - lumped the ball forward in the general direction of Jonathan Walters and Shane Long and hoped that a midfielder would latch onto a second ball.

You can’t hope to retain possession if your defenders are not looking for the short pass inside and constantly kick the ball long. Worse still, is when the holding midfielder - James McCarthy against Georgia - is uncomfortable with accepting the ball from his defenders.

Either the manager’s instructions were to go long or the players simply ignored the manager’s demand to keep the ball. Against Georgia, the Republic looked devoid of strategy and couldn’t expect to establish any rhythm in their play or control the game because the defenders were so anxious to get the ball from A to B, by-passing the midfield entirely.

Georgia played well on the night and proved they have quality with their 1-1 draw away to Wales a few nights later. But to throw endless bouquets at the feet of Georgia merely distracts from the shortcomings of Ireland’s route one approach and its inherent weaknesses that are likely to be exposed later in the campaign.

The configuration of Ireland’s midfield didn’t look right either against Georgia. McCarthy’s strength is breaking down opposition attacks, not initiating them, while Jeff Hendrick - suspended for the Moldova game - seemed to play too high and didn’t really go looking for the short pass from his full-backs or central defenders. He was completely lost to the game.

Things were better four nights later in Moldova and the change in fortunes was down to one factor: Wes Hoolahan. Courage on a football field comes in different forms.

Hoolahan is the most courageous player in the Republic’s ranks. And it takes courage to select him. He demands the ball in tight areas. He demands that his team-mates make angles to accept the short pass.

He’s the one Irish player who establishes rhythm, an element of control for the team. The 34-year-old had a hand in two of Ireland’s three goals on the night.

But too often, players of Hoolahan’s ilk are criticised for what they can’t do on a football field rather what they can do. With Hoolahan in the team, Ireland have a chance. Without him, O’Neill’s midfield looks rudderless.

Let’s hope there’s a midfield berth reserved for the little metronome in Vienna next month.