IN THE second of our two-part feature on Peter Withnell, the former Down forward tells Neil Loughran how he batted away senseless sectarian barbs and reflects on a premature end to his days wearing red-and-black…

“WRITE away by all means, you’re the journalist, but please just don’t make it about religion.”

It’s no wonder Peter Withnell is still wary 25 years on. In the months after his All-Ireland winning exploits with Down the public, particularly inside the county, wanted to know more about the man who had come from nowhere to the steps of the Hogan Stand on the third Sunday in September.

First thing's first - Withnell, where was the name from? Someone had heard he was a Protestant. Another rumour doing the rounds suggested he was in the RUC.

In the pre-ceasefire era, this wasn’t the kind of talk you wanted flying about the terraces.

As if sinking Kerry in the All-Ireland semi-final with strikes off his left and right shouldn’t have been enough to end talk about what foot he kicked with, such talk refused to die: “I’ll be quite honest - I did not know and still don’t know what Peter’s persuasion is. I’ve no idea,” says Pete McGrath, the man who master-minded Down’s All-Ireland wins in 1991 and '94.

“I couldn’t have cared less if he had been a Quaker, a Mormon, a Free Presbyterian or whatever. Inter-county footballers heading into an All-Ireland campaign, the last thing on their mind is religion, apart from the prayers they say at night.”

Inevitably, the matter infiltrated Withnell’s life on the field, with opponents giving him plenty in the hope of drawing a reaction. Even in the Irish League soccer career that intersected and eventually superseded his Gaelic football days, sectarian barbs became a common occurrence.

The name-calling often brought the best out in him, he says, though Withnell admits he found it bewildering at the time - and still does to this day - that people took such an interest in his background.

“To be honest, the talk about religion, I hate that s***. That isn’t me, it never has been me," he says.

“My mum used to say ‘clean the dirt around your door, then you can look at somebody else’s’. A lot of those people are the ones who go to matches week-in, week-out and want to tar some young fella… sport shouldn’t be that way, and thankfully now it doesn’t seem to be.

“I come from a mixed marriage but religion was never mentioned in our house, all my parents wanted was a peaceful life. My attitude was always ‘call me what you want, next minute you’ll be on your ass’. I just waited on that 50-50 challenge to burst that guy.

“I didn’t give off or cry if somebody rattled into me and hit me a dig or whatever. That’s not me trying to sound like the big lad, because I never saw it like that. No matter what happened on the field, I would always have shaken hands with my opponent after the game. It just went with the territory I suppose. But once the game was over, it was over, history.”

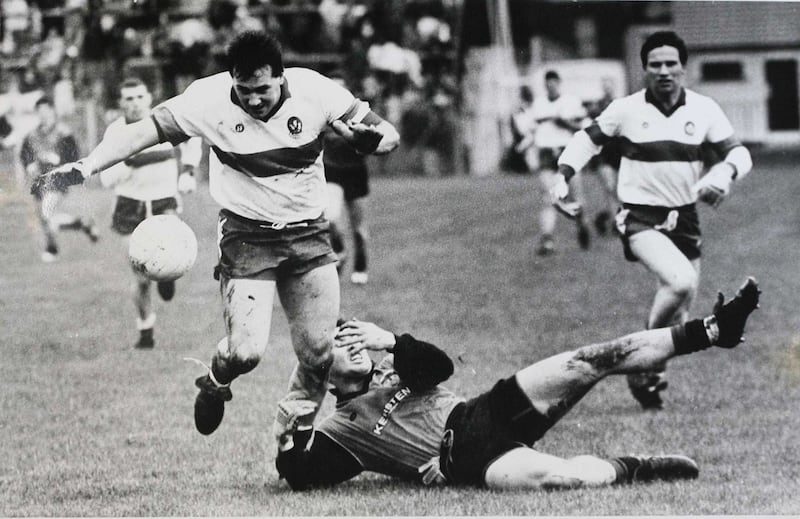

He may dismiss it as “sticks and stones”, but occasionally Withnell would rise to the bait. The kind of player he was - standing six foot tall and built like a brick outhouse - meant he often found himself at the epicentre of any physical tussles taking place.

That confidence, that swagger, that attitude, it must be in his DNA, right? Wrong. His off-field persona is at odds with the perception held by most people who have followed Withnell’s sporting career.

Quiet and extremely private, being in the public eye never sat comfortably. He viewed football, like soccer later on, as a job. Once he crossed the white line, regardless of code, his only concern was doing the best he possibly could for himself and his team-mates but when the big stage arrived, you could always rely on Withnell to deliver.

Stevie Small played alongside him at Cliftonville in the late 1990s, the latest stop on a nomadic but goal-laden Irish League career that also took him to the Reds’ north Belfast rivals Crusaders, Ballymena United, Newry City and Glenavon before drawing to a close at Lisburn Distillery in 2006.

Reds boss Marty Quinn had been keen to bring Withnell to Solitude for years and, after two failed attempts to prise him away from League of Ireland side Dundalk, finally landed his man in January 1999.

Cliftonville had won the league the previous April but when Withnell arrived midway through the following season they were struggling badly and ended up finishing second bottom of the table and facing a relegation play-off with Ards.

Cometh the hour though, cometh the man as Withnell came off the bench to score the winning goal in the away leg before bagging a hat-trick at Solitude to help secure the club’s top-flight status.

“That was his moment, those two legs, and he’ll always be remembered fondly at Cliftonville because of that,” says defender Small.

“One thing that sticks with me about Peter was his confidence on the big stage. When some others were nervous, Peter was like ‘this is brilliant’. He lived for that kind of pressure.

“When Marty Quinn was trying to sign him, he says, ‘I want to put crosses into the box, in Tim McCann we’ve got the quickest player in the Irish League’, and Peter turned round and said ‘you haven’t seen me yet’.

“Tim was lightning quick, but Peter didn’t lack for confidence. He just had that belief in himself, and it stood to him.”

******

WHEN you’re standing on the top of the mountain, the only way to go is down.

After the highs of 1991, Withnell was one of Pete McGrath’s blue-eyed boys, but cracks were starting to appear in their relationship. Soccer had always been in his blood - McGrath knew this. Often, Withnell would show up at training wearing the jersey of one English club or another.

On other occasions, he would infuriate the Down boss by heading the ball into the back of the net before wheeling away in celebration. His team-mates laughed and, so long as he was dedicating himself exclusively to Gaelic football at weekends, McGrath could see the funny side too.

The lines became blurred, however, when he started playing at a semi-professional level for Dundalk. Out of work and offered a few quid to kick a bit of ball, Withnell didn’t see the issue.

McGrath did. Playing soccer one day, Gaelic football the next was simply not an option under his regime: “His soccer career was becoming a factor that was taking away from what he could contribute to the Down senior squad,” says McGrath.

“For anyone to try and balance a semi-professional soccer with a full-blown inter-county career was just impossible, despite the fact he was a very fit fella. He was missing out on other things - maybe working harder on Gaelic football to bring other dimensions to his game.

“For a player to become an even better player, like the way Eoin Liston did for Kerry, you have to be focused exclusively on what is a very demanding sport. Peter was being pulled in different directions and it did set him on a collision course with his inter-county career.”

Withnell’s attempts to play down his extra-curricular activity didn’t help. Team-mates recall him being asked outright by McGrath if he had been playing soccer at the weekend. Withnell would answer no. McGrath would ask again.

“Are you sure Peter?”

“No, definitely not Pete.”

Then, McGrath would refer to a newspaper cutting showing Withnell playing for whatever club he happened to be featuring for that weekend. Eventually, he could offer up no more denials, as the other players sniggered like schoolboys in the background.

“I was in the public eye because of soccer and I couldn’t hide it,” he says with a rueful smile.

“I did try but then somebody would show Pete my picture in the Sunday World or the Sunday Life. When you’re in and out of work and somebody offers you a nice pay packet every week, you know...”

Withnell was still an automatic pick for most of 1992 when Down lost to Derry in the Ulster semi-final, but the years that followed saw him fall down the pecking order. By the start of the 1994 campaign, which would end in a second All-Ireland title in the space of four years, Rostrevor’s Aidan Farrell was the man wearing number 14 while Withnell stewed on the sidelines.

“When me and Pete locked horns, it was probably the beginning of the end,” he admits.

“Pete’s rule was ‘no soccer’. He’s a true Gael and that’s the way he wanted to run his team and he was quite entitled to do that. Maybe I thought I was bigger than Pete. Players have to be handled in different ways, some like an arm put around them, some need a few f**** thrown at them. I think I needed an arm around me. I can see now that he did it for the best of the team. But I don’t have any regrets over what I did on Saturdays.”

But surely there are regrets that, when the Mourne county silenced the Hill by beating Dublin in the 1994, he was on the periphery? That but for his self-inflicted wounds, he would have been out there enjoying a second All-Ireland title?

Withnell came and went for a couple of years after 1994 but as some of the old guard fell away, so too did he, pulling on the red and black jersey for the last time in 1997. Soccer became the priority yet, no matter what he went on to achieve elsewhere, there was always a sense of regret about how his Down career had petered out so prematurely.

“I could’ve done more - I quit too early," he says.

“It’s a regret on my behalf but I think it’s also a mistake on Pete’s behalf. I had a great relationship with Pete - I still have a great relationship with Pete - but I think, because I was equally good at soccer, that heavy hand came down and I was punished for it.”

In the midst of it all, McGrath insists, the pair always remained on amicable terms: “Eventually, it meant his Down career came to a premature end because he could have played for a number of years longer than he did.

“There would’ve been issues, we would’ve had differences of opinions, but in the middle of it all I never fell out with Peter Withnell.”

******

FORTY-SIX years of age. Where did the time go?

Sat amongst former comrades as they waited to be paraded before the All-Ireland final meeting between Dublin and Mayo, it was a strange feeling returning at Croke Park. Standing in the middle of the field he once graced to such devastating effect, receiving polite applause and offering up a wave every now and again, Withnell couldn’t escape the nagging feeling that he didn’t belong.

This pomp and ceremony wasn’t really for him and, besides, did any of those people even know who he was? The years after the sun goes down on a sporting career can be hard. Until recently, Withnell was still lining out for the Down masters side and played home and away games for a Northern Ireland over-40 select in soccer.

If there was a charity game going, a fundraiser or just a kickabout, just give Peter Withnell a call and he’ll be there in a flash. He never fell out of love with sport, with the buzz of competition.

Now, working away from home most of the week, he simply doesn’t have the time. He goes out for the odd run to keep himself in check, but the buzz has gone. How do you go about replacing it?

You don’t, his simple response: “The hype’s gone, you’re out of the bubble and you’re on your own.

“It is what is. That was a part of your life but it comes to an end. Football’s short-lived and it’s hard to leave behind, but you’ve no choice. You put your energy into other things - your family, your work. It’s that simple.

“Don’t get me wrong, it’s nice when somebody recognises you or comes up and talks about Down, or your days at Dundalk or whatever. But you don’t hang on to that stuff forever. Sport was a big part of my life but it isn’t all that I am.”

Not that anybody who was stood on the Hill those momentous days in 1991 could ever forget Peter Withnell, no matter how hard they tried. Neither will Tom Spillane, Mick Lyons or the many full-backs, midfielders or centre-backs he came up against during a long and distinguished career.

“I played with a great bunch of players from one to 30. It wasn’t one to 15 that won that All-Ireland, it was all of us," he says.

“We all have that respect for each other, that bond. I have the utmost respect for all the guys I played with and more than anything, you miss the craic and the banter. That’s why it was great to see everybody again during the summer.

“Some people might look back and think you were good, others that you weren’t fit to wear the Down shirt, and there’s others who’ll say you were in the right place at the right time. I just think I was lucky to play in a great team with a great manager at a great time.”

“The fact is he reached the very top in Gaelic football,” says Pete McGrath.

“When Peter Withnell was in his heyday, he blazed a trail and made a massive impression on people not only in Down, but on people who saw Down play in those years - he was like a meteorite going across the sky.”