“I knew he’d won the fight, fair play to him, but from that night all I was thinking was… where do I go from here?”

DESPITE Barney Eastwood’s promise to Paddy Maguire at the Ulster Hall, it was far from certain that a rematch between Davy Larmour and Hugh Russell would ever take place. First of all, Larmour wasn’t sure what his future held.

He felt he got his tactics wrong the first night and was sure he wouldn’t make the same mistakes again. Yet that defeat was also the sixth of a tough career. At 32, 33 in a couple of months, how many times could he go back to the well?

There was also the small matter of Russell getting past belt-holder John Feeney on January 25, 1983 in a contest listed for 15 rounds (incidentally, the last British title fight ever scheduled for that distance).

At 24 Feeney was only a year older but, as a fully-fledged bantamweight, held a natural physical advantage over his Belfast counterpart.

“Truthfully, I think when Feeney saw the fight, he saw me as a flyweight,” says Russell.

“He looked on it as an easy defence,” agreed Larmour, who beat Dave George on the undercard of Russell-Feeney in a fight which reinforced his belief that the end was nigh.

“I stopped him in the sixth round,” he said, “but Dave was giving me the mother and father of a hiding before that; boxing the head off me.

“I realised during that fight that my sell-by date was up. What I was getting now was a bonus. I was at my peak in the ‘70s, my sell-by date was passed and there was nobody more aware of that than me.”

Larmour showered and got himself patched up before wandering out into the packed hall for the main event.

Still mulling his below-par performance against George, a Russell rematch couldn’t have been further from his thoughts.

And, he insists, that wasn’t the reason for cheering his fellow Belfast man to victory when Feeney’s frustrations got the better of him, a headbutt in the 13th round leading to the Hartlepool man’s disqualification.

“No, not at all,” protests Larmour.

“That night I was supporting Hugh Russell as much as anybody in that hall. I wanted him to win that fight, not because of a rematch or anything like that. I wanted him to win because he was one of our own.”

The British bantamweight title was back on Irish soil for the first time since Paddy Maguire, now Larmour’s trainer, had brought it home from London eight years earlier.

It was all the motivation Larmour needed for one last crack as Eastwood kept his word and signed up for the rematch.

For Russell’s part, another win over Larmour would see him one fight away from winning the Lonsdale belt outright. And psychologically, having had his hand raised the first time, he held the edge.

“When I got offered the second fight with Davy Larmour, I saw that as a second notch on my belt.

“I had fought him, mentally it wouldn’t have been as hard because I’d already been in with this guy I had looked up to and held my own and got the decision. All that stuff I would have worried about before the first fight wouldn’t have been in my head the second time.

“What I never took into account was the training period for a 15 round fight, and then fighting somebody four weeks later.”

****************************

THIRTY-SIX days. Nowadays, some fighters wouldn’t even be seen back in the gym for that period after a fight.

But this was the amount of time Davy Larmour and Hugh Russell had to recover from their last bout before getting fully up to speed for the next when the rematch date was set for March 2, 1983 (a Wednesday night this time).

That they were to face each other, with memories of their October bloodbath still fresh, makes the time-frame all the more curious. Russell, in particular, barely had the chance to enjoy the biggest win of his career before being thrust back into the ring.

“Even by the circumstances of the day, that was very soon,” admits Eastwood.

“Paddy Maguire was at me… Paddy was a protégé of mine, we were very friendly, and he was saying ‘you’re keeping your word, you’re keeping your word’.

“Russell felt he was in good shape. Mentally he was good, and we thought it would be an easier fight for him this time. Maybe in hindsight it wasn’t a great idea, but these things happen.

“I knew it would be a cracking fight again but, looking back, it was probably a couple of months too soon.”

“When you’re in your early 20s you think you can walk through walls, and that was my attitude,” adds Russell.

“Any decisions Barney Eastwood and I made, we were both very clear on. There were no decisions made without asking because, at the end of the day, I was the guy putting my foot over the rope.”

Adding another layer of intrigue was the fact it would be staged at the King’s Hall – the first big-time boxing event to be held there since John Caldwell and Freddie Gilroy went to war at the tail end of 1962.

This was the opportunity Eastwood had been waiting for.

“You couldn’t get the King’s Hall unless you had something pretty special.

“It was the place and right from away back, even to the time of Rinty Monaghan. There was always one or two shows there a year.

“That was always the big night of the year for boxing in Ireland and these two guys had helped bring that buzz back to Belfast.”

Both camps got down to work and where making weight was never an issue for the lighter Russell, Larmour tipped the scales at 11 stone three weeks out – a full two stones and eight pounds over the bantamweight limit of eight stone six.

In the days after he found himself running backwards on the track at Paisley Park, Maguire flaking the backside off him with a wet towel in a bid to whip his charge into shape.

By the time fight week arrived, though, Larmour was locked and loaded. He and Russell both happily posed for pictures with Caldwell and Gilroy as the build-up dominated front and back pages.

This time television cameras would be there too, with the BBC broadcasting the fight live. The first one was big, huge in fact, but it was clear that they had now moved into another stratosphere.

And Larmour was determined that, this time around, there would be no repeat result.

“I remember on the night of the fight we were coming over the Hightown Road and, in the distance, I could see the King’s Hall,” he says.

“Paddy and my brother John were in the car too giving their opinions on this, that and the other, and I just said ‘do you know who’s going to win this fight? The one who wants to win it the most - and that’s me’.”

****************************

IT was a love affair that had started in 1958 while watching the great Sugar Ray Robinson versus Carmen Basilio. A six-year-old Davy Larmour is transfixed by the 12-inch black and white television screen, the picture made bigger by the magnifying glass bolted on to the coffee table in front.

Dad Samuel is sat in the corner of the room, smoking his pipe. The Lone Ranger has just finished, normally the young man’s cue to head off and expend energy elsewhere.

But at 1.10pm every Saturday afternoon, the BBC broadcast America’s Fight of the Week. His three uncles – Brian, Frankie and John Briers – all boxed, but this was Larmour’s first taste of the noble art, as demonstrated by some of its most famous exponents.

He was hooked straight away.

“I remember them coming out and the bell going,” he recalls, “there was just something about the sound of that bell ringing that really got a hold of me.”

And it was that sound that sparked Davy Larmour into action on a night when, by his own reckoning, he wouldn’t be denied.

The noise inside the King’s Hall was like nothing either fighter had experienced before as a relaxed attitude to attendance limits once again ensured the venue, just as had been the case at the Ulster Hall five months previous, was bursting at the seams.

“Whatever it was about the King’s Hall, the sound started to echo,” says Barney Eastwood.

“There was a limit of 6,500 on it at the time I think, but there was more than that I’m sure. It was probably more like 8,000, and when you had that many people inside, you couldn’t hear your ears.”

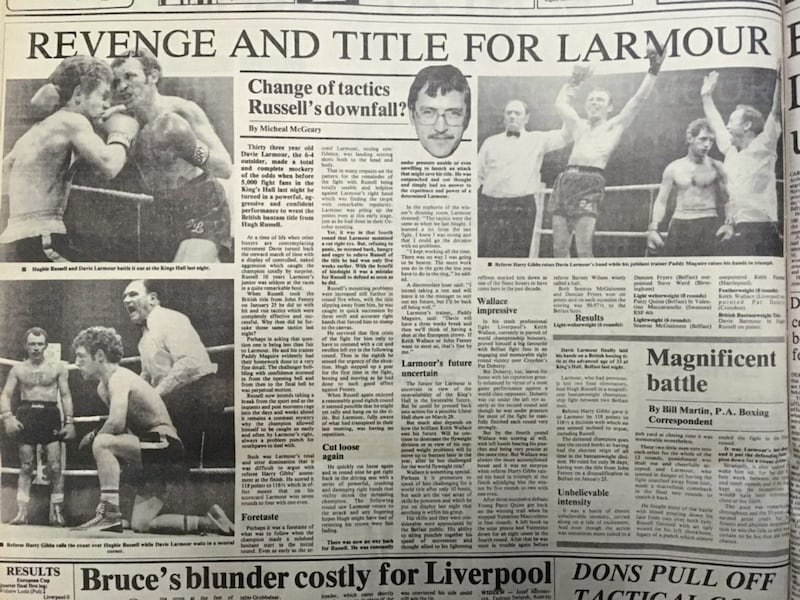

Russell came out of the blocks quickly, boxing beautifully on the back foot to take control in the early rounds. But when he walked on to a Larmour right hand in the fifth, alarm bells were ringing.

Visibly tiring as the fight wore on, despite bouncing back from that knockdown impressively, an exhausted Russell was hanging on towards the end as Larmour piled on the pressure, sensing his opportunity.

“I just couldn’t perform,” says Russell.

“People will never realise how well I did to get through 12 rounds because there’s nothing left in your body. All of a sudden you were getting hit with punches you wouldn’t normally be getting hit with.

“You get to stage where there’s a certain level of tiredness and then something kicks in… whether that’s guts or balls or whatever, I don’t know.”

“It’s an overriding thing,” says Larmour.

“In about the fifth or sixth round my head seemed to split down the middle…”

“That was my right hands,” smiles Russell.

“It might have been, but one half was saying ‘you’re tired’ and the other part’s saying ‘when this bell rings you have to get up’.”

“You had to get up or I’d have thrown you out,” laughs Maguire, before Larmour finishes.

“When the bell went that time I was taken right back to America’s Fight of the Week. It resonated with me and I had to get up.”

A voice from the past also played a part in the Larmour revival during the latter stages

“There’s things that stand out in my memory - spooky things.

“Mickey Tohill was a southpaw; beat me twice. Sammy Vernon, southpaw; beat me twice. Hugh, southpaw - he had already beat me in the first fight.

“So I’m sitting in the corner, Paddy’s doctoring my eye up, Harry Robinson’s giving me a drink, and from out of nowhere it was as if someone was leaning over the ropes, speaking into my ear.

“What shocked me was the guy who’s voice it was, he had died 20 years before. He was an old guy who trained me at Springmount amateur boxing club, Jimmy Hamilton.

“The voice said ‘the best way to beat a southpaw is to throw plenty of right hands’. It was as if he was sitting in my corner. I looked around in shock but there was nobody there of course.

“It wasn’t until that point that I started throwing single right hands.”

Wherever that moment of inspiration came from, it worked a treat as the right landed with increasing regularity, and Larmour’s hand was raised by referee Harry Gibbs seconds after the final bell sounded.

It may not have been as bloody an affair as the first, but it was no less gripping, and no less memorable for those lucky enough to have been inside the King’s Hall.

“They were fights that any boxing man would remember for a lifetime,” says Eastwood.

“Those fights would have meant as much as a world title fight to boxing fans in Belfast. When you get two fighters of that calibre, two guys from Belfast, from two different areas, you have a great combination.”

“Everybody loved the fights,” says Russell before motioning in Larmour’s direction, “but me and him had to go through it.

“Everybody else enjoyed it, but we suffered it.”

****************************

THE legacy lives on. Thirty-five years later, Hugh Russell and Davy Larmour still get stopped in the street. Heckled by bus drivers.

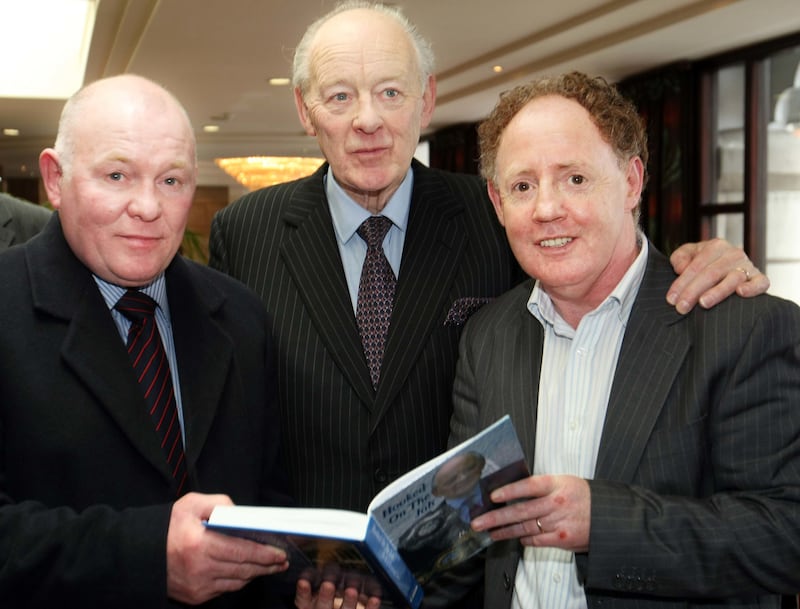

They can sit here now like old friends where, for 24 gruelling rounds once upon a time, they behaved like mortal enemies.

Yet at the back of it all is a pride to be associated with each other, and with a seminal moment in Belfast’s illustrious boxing history.

“What gives me a chuckle,” says Russell, “and certainly makes my kids laugh, is when you’re walking down the street and people stop you and say ‘do you remember the fight with you and Larmour? What a night’.

“I still say I did you the best turn in the world - we all ended up with Lonsdale belts around us. I remember seeing the photograph you got done with the belt around you.

“I was looking at it, and all I could say was ‘that’s my f**king belt!’”

A third match was talked about, but never with any serious or realistic intent.

Russell decided to move back down to his natural flyweight, and won another British title 10 months later.

But less than two years after the second Larmour fight ‘Little Red’, at 25, hung up the gloves, never to return.

Larmour stepped between the ropes just once more, stopped in three against John Feeney. By winning the British title eight months earlier, however, he had achieved a lifetime’s ambition and knew when it was time to go.

For both men, there were no second thoughts.

Yet they can never escape, nor would they want to, the magical memories created all those years ago.

“I drove a taxi for a while after finishing, and I remember bringing these guys to one of the McGuigan fights,” recalls Larmour.

“The guy sitting in the front seat was talking away to me like I was his brother. These other three guys were in the back and this guy in the front says ‘do you remember the night Russell and Larmour fought?’

“The three boys in the back jumped on it and they were all talking away ‘remember this happened, remember that punch’ – they were part of that fight.

“They hadn’t a clue who was driving, and I didn’t tell them,” he continues, before adding with a smile, “I was enjoying listening to them too much.”

“Out of everything, they’re the fights everybody talks about,” agrees Russell.

“As you get older, you maybe appreciate it more, and become a lot more proud of what you’ve done. They’re memories you can’t put a price on.”

“They’re fights that are remembered for all the right reasons, and nobody got hurt. That’s the most important thing…” adds Maguire, with the conversation drawing to a close.

But Russell can’t resist having the last word.

“...and I never even got cut!”

The three burst into laughter as they get ready to go their separate ways.

Hugh Russell and Davy Larmour shake hands and pose for photos, another yarn to tell the grandkids banked before heading off in different directions.

Just as they did all those years ago.