Lab-grown small blood vessels help point to potential treatment for a major cause of stroke and vascular dementia, a new study suggests.

University of Cambridge scientists have used the models to demonstrate how damage to the scaffolding that supports these vessels can cause them to leak, leading to conditions such as vascular dementia and stroke.

The study also identifies a drug target that can plug these leaks and prevent so-called small vessel disease in the brain.

Dr Alessandra Granata, from the department of clinical neurosciences at Cambridge – who led the study, said: “Despite the number of people affected worldwide by small vessel disease, we have little in the way of treatments because we don’t fully understand what damages the blood vessels and causes the disease.

“Most of what we know about the underlying causes tends to come from animal studies, but they are limited in what they can tell us.

“That’s why we turned to stem cells to generate cells of the brain blood vessels and create a disease model ‘in a dish’ that mimics what we see in patients.”

Research suggests cerebral small vessel disease (SVD) is a leading cause of age-related cognitive decline and contributes to almost half (45%) of dementia cases worldwide.

It is also responsible for one in five (20%) ischemic strokes – the most common type of stroke – where a blood clot prevents the flow of blood and oxygen to the brain.

Conditions such as high blood pressure and type 2 diabetes are associated with the majority of SVD cases and tend to affect people in their middle age.

But there are also some rare, inherited forms of the disease that can strike people at a younger age, often in their mid-thirties.

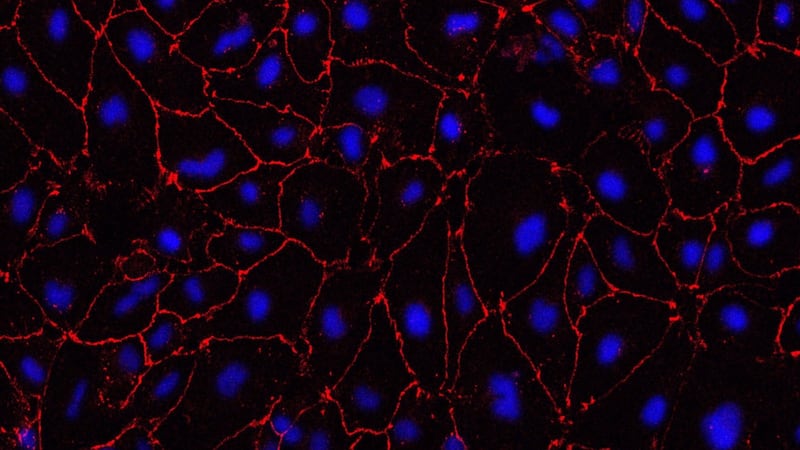

Using cells taken from skin biopsies of patients with one of these rare forms of SVD, which is caused by a mutation in a gene called COL4, scientists at the Victor Phillip Dahdaleh Heart and Lung Research Institute, University of Cambridge, created their lab grown vessels.

They reprogrammed the skin cells to create induced pluripotent stem cells – cells that have the capacity to develop into almost any type of cell within the body.

The team then used these stem cells to generate cells of the brain blood vessels and create a model of the disease that mimics the defects seen in patients’ brain vessels.

Human blood vessels are built around a type of scaffolding known as an extracellular matrix, a net-like structure that lines and supports the small blood vessels in the brain.

The COL4 gene is important for the health of this matrix.

In their disease model, the researchers found that the matrix is disrupted, particularly at its so-called tight junctions, which zip cells together.

This leads to the small blood vessels becoming leaky – a key characteristic seen in SVD, where blood leaks out of the vessels and into the brain.

A class of molecules called metalloproteinases (MMPs) were identified as playing a key role in this damage.

MMPs are important for maintaining the extracellular matrix, but if too many of them are produced, they can damage the structure.

When the team treated the blood vessels with drugs that inhibit MMPs – an antibiotic and anti-cancer drug – they found that these reversed the damage and stopped the leakage.

Dr Granata added: “These particular drugs come with potentially significant side effects so wouldn’t in themselves be viable to treat small vessel disease.

“But they show that in theory, targeting MMPs could stop the disease. Our model could be scaled up relatively easily to test the viability of future potential drugs.”

The study, published in Stem Cell Reports, was funded by the Stroke Association, British Heart Foundation and Alzheimer’s Society, with support from the NIHR Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre and the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Programme.