Ask Andrew Kiln how he is and he’ll say he feels as if he’s won the lottery. That’s because Andrew (76), from Ramsgate in Kent, is the first person in the UK — and only the second in Europe — to have a game-changing heart operation.

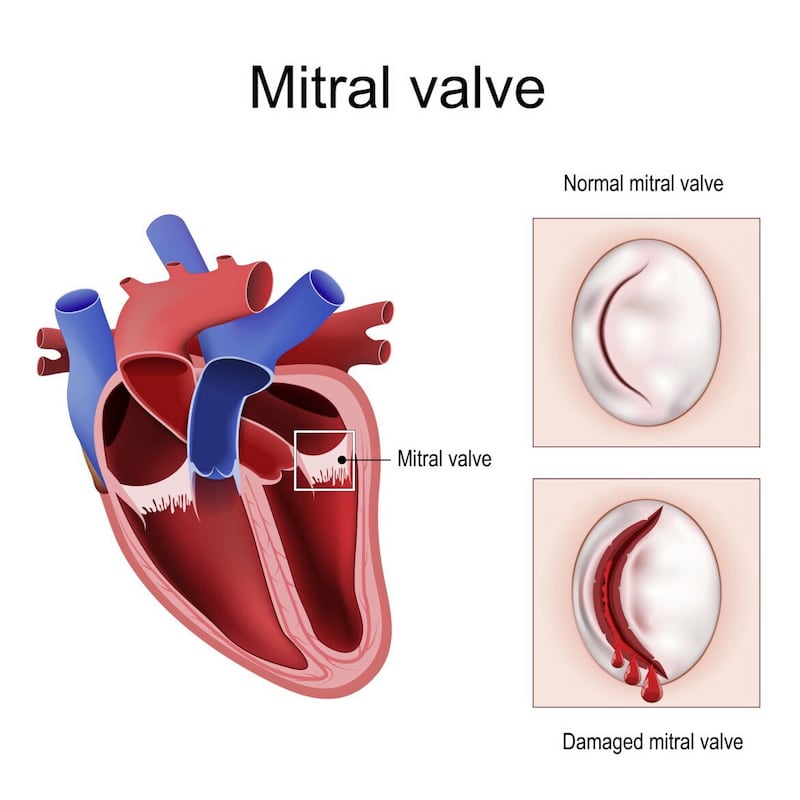

During an hour-long procedure, surgeons replaced the grandfather-of-seven’s leaky mitral valve, the ‘gate’ that controls the flow of blood into the left ventricle, the main pumping chamber of the heart.

In its place they put an artificial valve, roughly the width of a pound coin and made from wire and the tough, fibrous tissue that surrounds a cow’s heart.

This major procedure was completed not by conventional open-heart surgery — which means cracking open the chest, leaving a scar up to a foot long — but through a tiny hole in the top of the thigh, which has barely left a mark.

Not only does the new technique cause less cosmetic damage, but it is faster and safer than open-heart surgery. Patients spend one or two days in hospital instead of a week (or more) and the recovery period is a few days, not several months.

Crucially, the new procedure is also suitable for patients who, like Andrew, cannot have open-heart surgery.

In his case, the scar tissue left behind after a major cardiac operation in 2010 could have hindered the procedure.

Now it’s hoped that thousands more like him will benefit from the new technique, since up to 40 per cent of those who need a mitral valve replacement are not suitable for conventional surgery.

"It’s potentially transformative for patients with heart valve disease," says Dr Tiffany Patterson, a consultant cardiologist at Guy’s and St Thomas’ Hospital, who operated on Andrew in February.

About 1.3 million people in the UK — including one in 10 over-75s — have mitral valve regurgitation, where the valve doesn’t close properly. Left untreated, this can lead to heart failure.

The oxygen-rich blood in a healthy heart flows from the left atrium (which receives oxygenated blood from the lungs) through the mitral valve and into the left ventricle below it. The left ventricle, the main pumping chamber of the heart, then pushes the blood out into the body.

In mitral valve regurgitation, because the valve doesn’t shut as it should, some of the blood leaks back into the left atrium.

This reduces the amount of blood (and oxygen it carries) making it out of the heart, meaning patients may be left tired and short of breath.

They can also suffer swelling in the abdomen and ankles: as the amount of blood reaching the kidneys is reduced, this can slow the rate at which they remove salt and water, causing the fluid build-up. As the leak worsens, the heart has to pump harder to distribute blood and the added strain can weaken it, causing heart failure — an incurable condition. About half of all heart failure patients die within five years of diagnosis.

Treatment for mitral valve regurgitation starts with adopting a healthy diet (to prevent heart disease that could further weaken the heart) and taking more exercise (to strengthen the heart) to stop it worsening.

Medication such as diuretics to help reduce swelling may be offered, and surgery can repair or replace the leaky valve. But this is major surgery. It involves making a large incision in the patient’s chest and temporarily stopping the heart (a heart-lung machine is used to keep blood circulating).

"It can take the best part of three hours to do under general anaesthetic," says Professor Simon Redwood, an honorary consultant cardiologist at Guy’s and St Thomas’.

"The recovery involves at least one or two nights in intensive care, approximately a week in hospital and probably a couple of months to get back to normal.

"In contrast, the new procedure takes about an hour; typically patients go home in the following day or two, and are back to normal pretty much straight away."

There is no need for a patient to be admitted to intensive care, and while there is a small risk from general anaesthetic (side-effects can include nausea, temporary confusion or, in rare cases, an allergic reaction to the drug used), this is reduced because the amount of anaesthetic used is far lower than in open-heart surgery, because it’s a shorter procedure.

To insert the new valve, called SAPIEN M3, a small incision just a few millimetres wide is made in the top of the groin and a catheter (a thin tube) is passed up into a large vein and pushed through to the right atrium.

Special tubing is then inserted through the catheter and wrapped around the faulty valve to create a doughnut-shaped docking station for the new valve.

The replacement valve is squashed down over a tiny deflated balloon and fed through the catheter until it reaches the required position.

The balloon is then inflated, expanding the new valve so it fits snugly inside the docking station — securing it in place inside the heart. The old faulty valve remains in place but its function is taken over by the healthy replacement.

Andrew, a retired Post Office worker and amateur football referee, is thought to have developed mitral valve regurgitation as a result of two heart attacks in quick succession in 2000.

Other patients get problems due to ageing (valve tissue can thicken as we get older, which stops the valves working properly), infections or congenital heart defects.

Doctors spotted Andrew’s faulty mitral valve during a routine check-up after a 2010 heart operation and decided it should be regularly monitored, as his condition at the time was mild.

But a 2020 check-up showed it had worsened significantly, even though he still had no apparent symptoms. With surgery not an option, Andrew’s future looked grim. "I didn’t want to go through another big heart operation at 76," he says, "so I just accepted it."

But early this year, his heart specialist, Professor Ronak Rajani, a consultant cardiologist at Guy’s and St Thomas’, told Andrew about a clinical trial of the new, minimally invasive procedure.

For the trial, 500 mitral valve regurgitation patients in six countries will have a SAPIEN M3 valve implanted using keyhole surgery. Two UK centres are taking part — Guy’s and St Thomas’, and Barts Hospital, both in London.

It is hoped that the device, one of two new groin-insertion mitral valves currently in trials, will last most patients at least ten years.

"When they said I was suitable for the new operation and I’d be the first in Britain to have it, it was quite a surprise," says Andrew.

"It was only six or seven months since they’d said they couldn’t do anything. I wasn’t anxious about being the first, even on the day itself. I just got on with it."

Andrew was awake and chatting to friends and family within a few hours of his operation, and up walking around the hospital ward the next day. He was discharged after two days.

"I remember Professor Rajani coming to see me after my operation, listening to my chest with his stethoscope and, with a smile as wide as the River Thames, saying: 'That’s lovely, you have no leaks at last.'"

With mitral valve regurgitation, the heartbeat has a characteristic muffled sound.

Just two months on from his treatment, Andrew is doing his own cooking and shopping and going for 20-minute walks at the weekend.

He has to take blood-thinning drugs to stop clots forming on his new valve, a potential hazard with valves made from animal tissue.

Prof Redwood, who co-led Andrew’s operation, says the new technique could, in time, be offered to most patients ruled unsuitable for open-heart surgery.

Tim Chico, a professor of cardiovascular medicine at the University of Sheffield, who is not involved in the trials, says such technology could help many sufferers, as an ageing population means more people will be too frail to withstand conventional surgery.

He explains: "For a significant number of people, the risks of open-heart surgery are too great. That number will inevitably increase as the population ages, so there is a pressing need for new procedures like this."

People can still join the trial by asking their cardiologist to refer them to Guy’s and St Thomas’.

Andrew, meanwhile, can’t believe his luck at being the first person in the UK to benefit. He says: "I feel like I’ve won the lottery. To be in such good health at 76 is like being a millionaire."

© Solo dmg media