IT is regularly claimed, as a feather in Christianity's cap, that it is a historical religion.

What such a claim normally seeks to assert is that Christianity is not based on myths and tall tales about the gods, but vitally intertwined with a particular historical figure, Jesus Christ.

Indeed this assertion is made by the New Testament itself at 2 Peter 1:16, where "cleverly disguised myths" are specifically contrasted with historical, "eyewitness", testimony to Christ.

And the fact that there has been so much interest, especially in recent centuries, in who Jesus really was - where he came from, what he was like, how he lived, what he taught, how he died, the meaning of belief in his resurrection, even sensational claims about Jesus, such as those popularised in books like The Da Vinci Code - could be seen as reinforcing the notion that Christianity is indeed a historical religion.

Yet such a view of Christianity as 'historical' clearly looks in one direction only: into the past.

It is, of course, open to anyone to look into Christianity's past and speculate about what actually happened or what could have happened in Jesus' life.

And no doubt such speculation, even if it sounds far-fetched at times, will always find new angles to develop in the search for the historical truth about Jesus.

But what might tend to be forgotten in this context is that to say Christianity is a historical religion means not only that it is concerned with the past, but it also means that it must be concerned with the future too - and maybe even more concerned with the future than with the past, if it is accepted that the openness of the future is finally more significant than the closedness of the past.

This is arguably an aspect of Christianity that in recent times has tended to be airbrushed out of popular discussion, just at a time when interest in Christianity's past was mounting exponentially.

To say Christianity is a historical religion means not only that it is concerned with the past, but it also means that it must be concerned with the future too

For to present the 'historical Jesus' of the past as a challenging, insightful, even enigmatic personality is no doubt a 'softer sell' for Christian apologetics, than to try to focus minds on the future and the impending approach of death as the inescapable 'moment of truth' for all.

The more recent focusing on Christianity's past might, in other words, plausibly be interpreted as a largely pragmatic, even shrewd reaction to an earlier, traditional, but now possibly embarrassing, stress on the future as the place where death awaits everyone.

Now it is true that the gospels do counsel us to be as "cunning as serpents", but only in conjunction with being as "innocent as doves".

And it may well be that the 'cunning' element in theological reflection has in recent centuries rendered the 'innocent' claims Christianity has also wanted to make practically invisible or inaudible.

As is well known, the Book of Revelation is very much, even almost luridly so, concerned with the future.

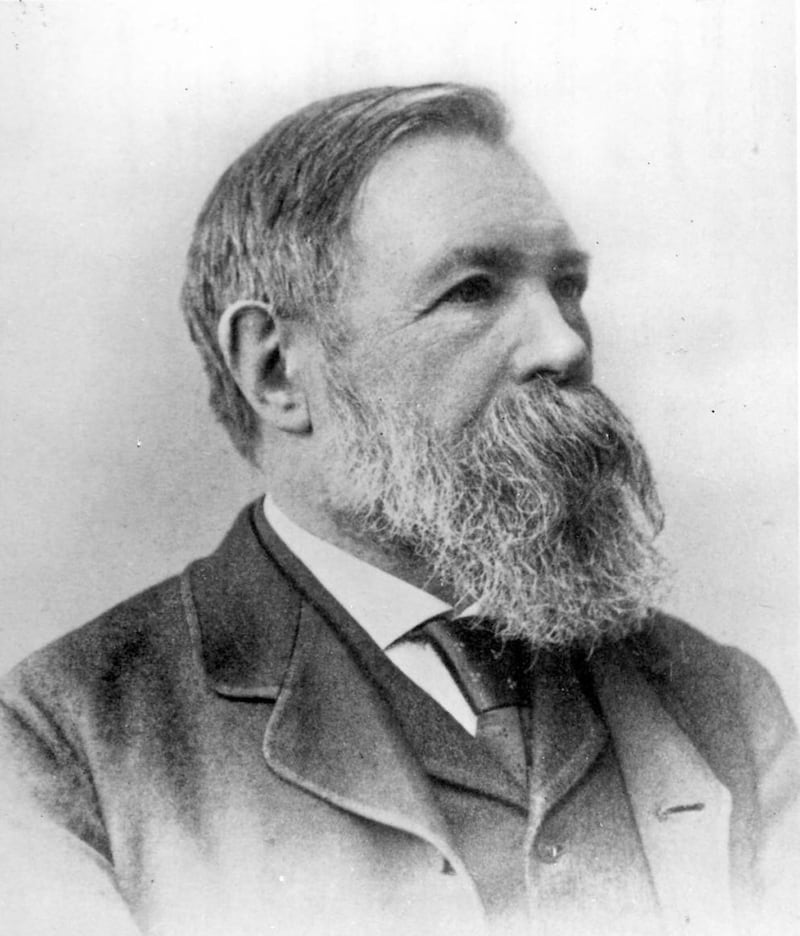

It is, fittingly, the last book of the New Testament. And while it offers little in the way of clues about the 'historical Jesus', and thus can be of little interest to would-be biographers of Jesus, it was regarded by Karl Marx's associate, Friedrich Engels, as "worth more than the rest of the New Testament put together".

Marxism, like Christianity, is concerned with history, and chiefly with its future.

The past can be known, in theory, but not changed, whereas the future is still open and hence is compatible with, if not an invitation to, hope.

Small wonder that Marxist societies have traditionally been uneasy about the implicit threat of competition posed by Christianity with its teaching about the fulfilment of human destiny, which can lie only in the future.

As has been frequently noted, the truth of a religion is often more acutely perceived by its foes than by its followers.

In this month of January, whose name is considered by some to derive from Janus, an ancient Roman deity, usually represented facing equally into the past and the future, it is perhaps quite appropriate to recollect the two directions the Christian movement is also involved with.

And it is perhaps even appropriate to have a rethink - which is what the much-abused term 'metanoia', or 'repentance', may really mean - about which direction is paramount.

Martin Henry, former lecturer in theology at St Patrick's College, Maynooth, is a priest of the diocese of Down and Connor