In his famous 1968 television address, Captain Terence O’Neill said “Ulster stands at the crossroads”. Although we no longer have a unionist prime minister, a similar speech from Jeffrey Donaldson tomorrow would probably state that it is unionism which is now at the crossroads.

Jeffrey’s crossroads choice is between returning to Stormont with a weakened DUP, or staying out and leaving the north’s governance in chaos. So how has the DUP led unionism into decline, while SF has guided nationalism into sectarian ascendancy?

Both parties are products of the Troubles. Triggered by the burning of Bombay Street, SF was founded in January 1970, as a breakaway from the republican movement’s left-wing policies. The DUP was formed in September 1971, as an alternative to the Ulster Unionists’ failure to quell the violence.

Both parties’ fundamentalism placed them on the same starting line, but SF has run a better race. Their victory has three main explanations: principles, publicity and political ability.

SF’s founding principles included abstention from Stormont and Leinster House; non-recognition of all courts; Irish independence from Britain and the EU; and support for violence to achieve an Irish republic.

- Patrick Murphy: Stormont isn’t working because the Good Friday Agreement isn’t working - we need a new system of governmentOpens in new window

- The DUP will not go into Stormont and SF will not go into Westminster. We are the only people in the world who vote for politicians not to represent us – Patrick MurphyOpens in new window

- Neither DUP nor SF will decommission their Stormont veto – Alex KaneOpens in new window

All these principles have now been abandoned. Interestingly, the more SF deserted what they said they stood for, the more popular they became. They achieved this through dynamic public relations, based on a wonderful flexibility with the truth and a reliance on the public’s short-term memory.

For example, they opposed the civil rights campaign, but then claimed that the IRA’s 30-year war was for equality. Without a decision by party members, or even a public announcement, they went from being anti-EU to pro-EU overnight.

The DUP largely stuck to its founding principles, which included fundamentalist Christianity, loyalty to the monarchy and conditional union with Britain. Unlike SF, it still opposes the EU. Retaining that principle has burdened it with a negative image, while abandoning the same principle has boosted SF’s reputation.

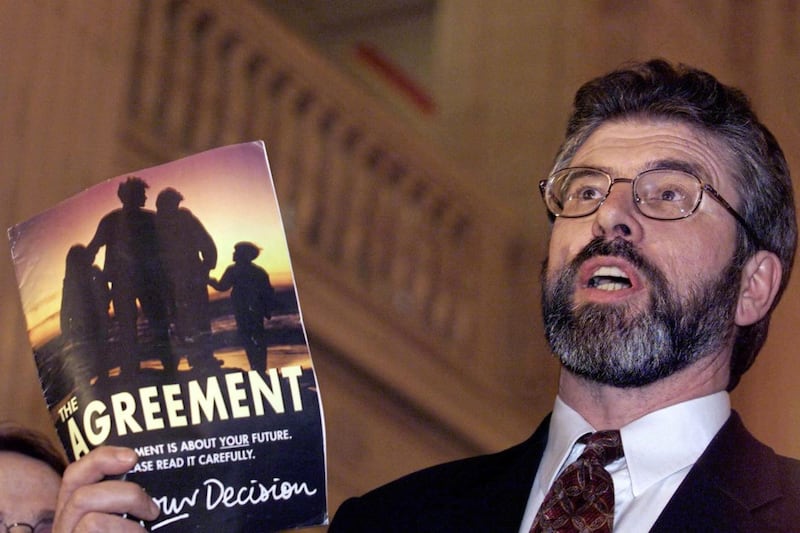

The difference between the parties is best illustrated by their attitudes to the Good Friday Agreement, which was a victory for unionism because nationalists agreed to partition. SF lost and did not admit it. The DUP won and did not know it.

SF called it a victory, although it was the IRA’s biggest military defeat since the civil war, as “Brits Out” became “Brits In”. Instead of celebrating victory and promoting power-sharing, the DUP adopted ridiculous positions on irrelevancies from flags to parades.

They displayed remarkable political innocence, or maybe arrogance. They believed Boris Johnson when he said he would stand by them and, unlike SF, they have not cultivated international friends (and wealthy donors) in high places. Instead the party seeks refuge with the Tory right in GB News, the lunatic fringe of broadcasting. The DUP’s problems today stem from 25 years of failing to appreciate a changing world.

The party has never understood public relations. Even today it fails to expose the trading difficulties which the Windsor Framework will soon create here, highlighting archaic constitutional law instead.

Perhaps the most interesting contrast in the two parties’ fortunes lies in religion. SF’s policy differs from the Catholic Church’s teachings on issues such as same-sex marriage and abortion, but its largely Catholic electoral support continues to rise. It is difficult to quantify, but SF appears to be as popular as the Church, because as many northern Catholics vote for SF as attend Sunday Mass regularly.

The difference between the DUP and Sinn Féin is best illustrated by their attitudes to the Good Friday Agreement. SF lost and did not admit it. The DUP won and did not know it

The DUP’s policies on both issues closely match the Catholic Church’s teachings, but few Catholics vote DUP. Did the Church’s decline help SF’s rise, while DUP policy has been restrained by the religious beliefs of many of its members?

The two parties’ one common trait is that both deny responsibility for the collapse of our public services. That was someone else’s fault.

So the moral of the story is that in politics here, populism beats principle and image runs rings around reality. Mind you, it is a lesson which also probably applies to life in general.