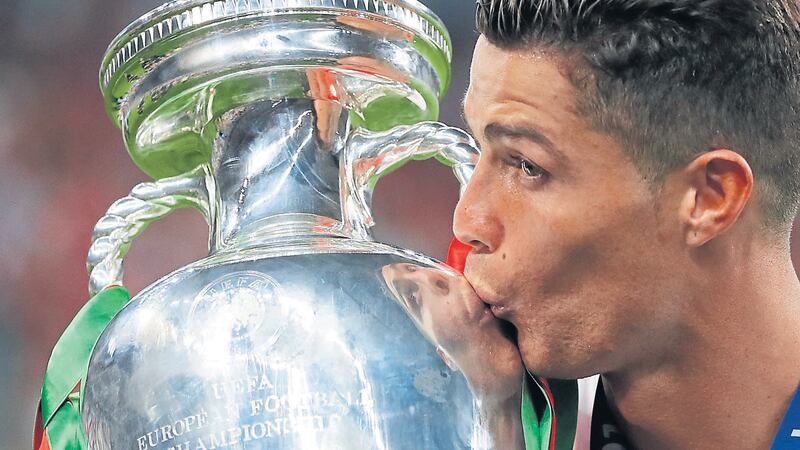

FOR lots of reasons it was a crying shame to see Cristiano Ronaldo limp out of last Sunday’s Euro 2016 final with a knee injury before half-time.

In the really big games you always want to see the best footballers playing with the handbrake completely off.

And Ronaldo is unmistakably one of the best in the modern game.

Still, the Portuguese superstar must take partial responsibility for getting injured in the Paris final.

When he received the ball in the seventh minute – only his second touch of the game – he was in a stationary position when he should have been on the move.

Ronaldo’s own narcissism was why he was forced out of arguably the biggest game of his career.

If you recall, football’s royalty wanted to put his foot on the ball, perhaps to pose and pout – as he had done for the last month or more – for the cameras on the sideline.

What did Ronaldo expect Dimitri Payet, his French assailant, to do? Stand back and admire his touch and poise?

Payet won back possession and made sure he left something on Ronaldo.

The action replay showed that because Ronaldo was stationary his left knee felt the full brunt of Payet’s tackle.

Outside of the Portuguese camp there wasn’t a whole lot of love for Ronaldo.

Indeed, the recent Euro finals conjures the unflattering image of the Real Madrid striker standing alone – always alone – hands on hips, displaying an exaggerated sense of disgust and contempt for a team-mate’s perceived inability to find him with a perfect pass.

The Euro 2016 highlights reel is filled with Ronaldo pouting, throwing his arms in the air, barracking team-mates, scuffing a hatful of chances and sitting away from his team during Portugal’s penalty shoot-out with Poland.

This is what greatness looks like on a football pitch.

And yet, for the past month a host of pundits were apologists for bad behaviour. Everything, they said, could be justified with a few goals.

Alan Shearer raved about Ronaldo’s goal record.

Rio Ferdinand, a former Manchester United team-mate, insisted that Ronaldo was a team player even though there was compelling evidence to the contrary nearly every time the spotlight fell on him during games.

Some ex-footballers, now working as media pundits, are inclined to over-reach themselves in trying to explain what life is like inside the changing room walls and passing it off as insight.

Gary Neville was perhaps the most guilty when bowing at the altar of Ronaldo.

Playing alongside the Portuguese star at Old Trafford, Neville insisted, changed his outlook on the game.

“It got to the point,” said Neville, “that as a right back in the 2006/07 season, I never complained if he could go off for 30 minutes and leave me constantly with two-on-one situations.

“He completely changed my opinions about the game. I’d always been taught that I must have a right winger in front of me, but I knew he’d go and win us the match.”

It was as if Neville was uncovering some vague intellectual notion of the game’s holy grail and in doing so he became an apologist for a team-mate with a poor work ethic.

Now, it makes sense for a player of Ronaldo’s goal-scoring ability to spend the vast majority of his time around the opposition’s penalty area – but if the structure of the Manchester United team was Ronaldo embracing his defensive duties and not to leave Neville exposed for vast chunks of games, then that was a player abdicating responsibility. Nothing else.

There was nothing profound in Neville’s words on Ronaldo.

Of course, it would be churlish not to acknowledge Ronaldo’s incredible transformation from a tricky, step-over wing wizard to a goal machine.

He has scored 331 goals in 313 games since the 2010/11 season. Incontrovertible evidence of greatness, you might suggest.

But there is a caveat to such statistics – and indeed the same applies to Lionel Messi’s equally scandalous goal-scoring exploits at Barcelona.

More than ever, the best players in the world migrate to the best clubs.

During the late ’80s and early ’90s, Italy’s Serie A attracted the best players like moths around firelight. But the world’s best didn’t always end up at AC Milan or Juventus.

Remember Zico ended up playing at unfashionable Udinese.

Diego Maradona signed for equally unfashionable Napoli.

Careca, the brilliant Brazilian striker, also played at Napoli during his peak years.

Gabriel Batistuta stayed loyal to Fiorentina during his best years.

Jurgen Klinsmann was brilliant for Inter Milan and Italy’s front two Gianluca Vialli and Roberto Mancini played at Sampdoria for a long time.

And for a couple of injury-free years, the San Siro was in awe of the languid grace of Marco Van Basten.

That’s the way football was back then. Most clubs could afford a marquee striker or playmaker and domestic competition was deeper as a result.

But football’s economy has radically changed.

Unfair TV deal means that there is no longer an even spread of talent across leagues.

Nowadays, the best players congregate at Real Madrid or Barcelona and consequently the quality of the domestic league suffers.

You can guarantee this coming season that La Liga giants Barcelona and Madrid will win more than a dozen games apiece by four or five-goal margins – and there will be a generous spread of hat-tricks between Ronaldo, Messi and Luis Suarez.

Given his record, many regard Ronaldo the best goal-scorer the game has ever seen – but the criteria applied are incredibly loose.

For instance, if Van Basten, Careca, Klinsmann or Batistuta played in today’s Real Madrid team, they too would flourish in the same way Ronaldo does – and their work-rate would easily out-strip the Portuguese.

They were also better team players than Ronaldo.

So when observers hail Ronaldo we must consider what exactly it is they’re hailing.

Is the bad behaviour part of it?

Is it the failure to give the obvious pass to a better-placed team-mate?

Is it another extravagant free-kick that misses the target?

Is it the failure to work as hard as his team-mates?

Is it the pouting?

Is it just the goals? And there have been plenty of goals.

Or is it how he’s tried to shoehorn the ‘I’ into ‘team’ for the best part of a decade?

Greatness, I suppose, comes in many forms, but there were many before him much superior.