HIS arrival into the action went pretty much unnoticed. Heading towards the final quarter of an hour, St John’s substitute Paul McGribben had just seen red following an off the ball incident.

Already they had lost full-back Ryan McNulty to a black card before half-time. Free-takers Brian Neeson and Padraig Nugent were having a nightmare in front of the posts.

When Domhnall Nugent came off the bench 16 minutes from time, the 14-man Johnnies trailed Portglenone by four and looked destined for the Antrim championship exit door.

Everybody piled up on the banks was immersed in the action as Paddy McBride led the revival, a Pearse Donnelly goal in the dying moments helping St John’s snatch an unlikely draw. When all looked lost, the west Belfast men had survived the storm and earned a second chance.

They weren’t the only ones.

One day at a time they say but, for Domhnall Nugent, that Sunday - September 8, 2019 - was special.

Not because he had come on and produced a Roy of the Rovers performance to drag St John’s back into it. He hadn’t. If anything, he was a peripheral figure following his introduction.

Instead, the magic lay in the sheer brilliant, beautiful normality of it all.

In the midst of the game’s chaotic climax, nobody in Ahoghill was wondering where his head was at. Or whether he was sober enough to play. Or where he was going after. That alone was a remarkable feeling.

Nine days earlier Andy McCallin had travelled to Newry to bring the 22-year-old home from Cuan Mhuire addiction treatment centre, 12 weeks after another St John’s stalwart, Paddy Hannigan, had taken him there, bedraggled and broken.

Heading for home marked the end of a long road, but left him right at the beginning of another.

******************

STANDING 6’2”, the frame that once packed in a fleshy 19-plus stone is gone (“I’m probably about 16… ish; another half a stone to go”). The eyes, at a time sunken and empty, are now clear and brimming with life.

Listening to Domnhall Nugent across a side office table at Homefit’s Hannahstown branch, it is hard to believe the person he is describing ever resided within the same skin.

“For anybody looking from the outside in,” he says, leaning forward in his seat, “they’d have thought my life was perfect.”

Head boy at De La Salle College, a three-time Ulster Colleges’ Allstar, centre half-back of choice with the Antrim senior hurlers at 18, part of the county football panel and St Mary’s midfield partner of future Allstar Cathal McShane.

Then there was the wide circle of friends, the warm embrace of a club he had known and loved since first stepping onto the Corrigan Park sod at three years old, and the beaming smile that lit up any room he entered.

If it all sounds too good to be true, well, that’s because it was.

“I went out to Boston for three months when I was 18, the summer after I finished school, and that’s probably when I started drinking regularly enough.

“But if you talk to any addict, there’s always something underlying. Your primary addiction is whatever you have going on in your life but your active addiction is alcohol, gambling, drugs… whatever it is, you’re doing that to escape reality, and that’s exactly what I was doing.

“I’ve had massive underlying issues from I was a kid, personal stuff, but I always used hurling and football as my escape. It was the best thing for me, the buzz I got off it.

“But Oisin McConville talks in his book about that moment when the final whistle goes and that dull feeling settles in. You’re on a pitch, doing well, ‘look at me’, and when it’s over, bang - you’re into the real world.

“I’ve had that feeling from I was under 10 the whole way up but I’ve only become really aware of my patterns of behaviour recently; running away from things, running up to my room to escape, running to stay in mates’ houses.

“I’ve run to Boston twice, I moved to England to play for Warwickshire. I was telling everybody I was doing it because I was getting these mad financial offers, but it was me running, thinking the grass was always greener on the other side.”

No matter where he went though, and no matter how fast or how far he ran, those demons followed him. Over time the boyish rush he got from bounding onto a pitch had been eroded, replaced instead by the comfort gleaned from the glass in his hand.

Relationships were becoming strained too, resulting in his controversial transfer from St John’s to west Belfast rivals Lamh Dhearg and an unforgettable conclusion to the 2017 Antrim football final between the two clubs.

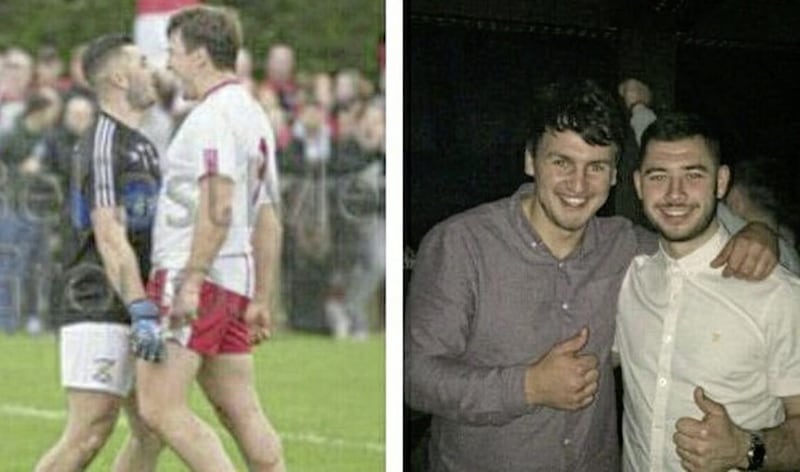

“With Lámh Dhearg having just gone two points up, Domhnall Nugent drove the ball off the tee at St John’s goalkeeper Padraig Nugent, who just happens to be his brother. Padraig reacted and, while it was a very brief and almost minor exchange, it was enough to earn the Johnnies’ goalkeeper a red card.”

He cringes slightly when The Irish News report is recalled. To add injury to insult, his father Paddy was over St John’s that year, while the show of sibling rivalry proved to be clickbait gold as the social media hordes descended.

A couple of days later Domhnall posted a picture of the brothers in arms, smiling and giving the thumbs up. Away from the public eye, however, lay a different story.

“I pushed myself away from my da, and Padraig especially. Our relationship fell away massively.

“I always thought he had the problem – when you’re caught up in addiction, it’s everybody else’s fault but your own. It got to the point where any time he came into my granny’s, I got up and walked out. It was terrible.

“I lost a lot of friends too… actually, I didn’t lose them, I pushed them away. The people who were telling me I needed to get my act together, I was turning it around that there was something wrong with them. I was associating myself with people who told me it was okay.

“A lot of people said that to me ‘right Domhnall, you need to sort yourself out, you need structure in your life’. I knew all those things, but I had lost control. I felt powerless.

“All my morals went completely out the window. Any time I’d get comfortable with anybody, I’d have done something to make it uncomfortable.

“I was more comfortable with uncomfortable; comfortable with chaos.”

The move to Lamh Dhearg was “another sign of me running,” but there are no regrets. From where he stands now, he has to take ownership of all the mistakes he made instead of grasping at excuses.

And there was good to come out of his days in red and white, not just a county football championship medal but, much more importantly, a friendship forged that would help him through the darkest of days.

“I met Emer there, and if I hadn’t met her I probably wouldn’t be sitting here.

“We’re not together any more but we’re still in contact and still friends… how she’s still friends with me is just baffling. It just shows you how good she is. She still helps me to this day, massively.

“She can obviously see that there’s good in me, and there is good in me. It’s just when you get caught up in the madness, so many people end up getting damaged.”

******************

A FEW weeks earlier he had run out at Croke Park wearing the white of Warwickshire in the final of the Nicky Rackard Cup yet there he sat, alone, perched on the edge of a single bed in a Birmingham box room.

It was a Friday morning sometime in the summer of 2018. That’s the extent of the detail Domhnall Nugent can recall.

In truth, despite the best of intentions from all sides, the move to England’s midlands hadn’t been good for him. Living in a house with three other young men, far away from the prying eyes back home, he could do what he wanted, when he wanted.

“Towards the end it was hell, mentally.

“I was telling family I was away working but it was the other lads who were away out working. I was sitting in a room with a bottle of Jameson. I didn’t see any point in me being here… I was just existing, I wasn’t living at all.”

In a rare moment of clear-headed clarity, Nugent booked a flight home. Emer picked him up from the airport that night.

But once back in Belfast, it wasn’t long until he returned to his old routines.

“I pretended everything was sweet – ‘aye, I’m just going to travel back and forward to England now, I’d rather be back here, it’s all good’, but things just got worse.

“I loved nothing more than sitting in the corner of a pub on my own pinting away because I didn’t have to slow down for anybody else. If anyone tried to talk to me I’d pretend I was on my phone.

“I used to go into the bar at 12 on a Monday and the bar man would have a bowl of stew ready for me. Sitting in there at 21, 22 years old… because I had played for the county and done a few things sporting-wise, I was talking to oul boys there as if I was talking about a career I’d had 30 or 40 years ago.

"I actually forgot how young I was."

He had been fixed up with a part-time job at his old school and started a small business, Black Mountain Sports, on the side, selling Gaelic gloves and other sports gear.

From the outside all still appeared rosy, but the cracks were beginning to widen and deepen amid the daily struggle to keep up with the catalogue of tales told.

“I was working in La Salle but then I ended up borrowing money off people, lying to people - making up reasons to borrow money…”

He pauses for a second and puffs out his cheeks, then continues.

“I had 10 different faces, and the amount of lies I told people… it’s so stressful, remembering what lie I told him, or him, or him… The wee business I started ended up just funding my addiction.

“I was pushing orders when I had no money to drink. I know if I went and did something like that next week, it would be a success, but that’s where my head was at then.

“I got paid on the 15th of every month from the school, so on the 30th I’d try to push an order, get five or six hundred quid up and that would do me until the 15th of the next month. I had it down to a tee.

“And whatever money I had, I spent it on drink.”

After returning from Birmingham Nugent transferred back to St John’s.

Heavier than ever, coaches put him on programmes and diets, but the will just wasn’t there once he went out through the gates.

“The lads were all happy to see me, but I’d still have been going to the bar on my way home and throwing a few pints into me.

“We played St Gall’s in a senior football league game in the middle of May and I was drunk. I’d been out all night, the match was at three and I’d been in The Rock at one. After that match I said to myself ‘Domhnall, you need to get yourself sorted here’.

“I was embarrassed, ashamed.”

The tipping point was just around the corner, but still he had to reach rock bottom before reaching out.

“I was living in an apartment and all I had was a tenner in my wallet, no electric, no gas. I remember thinking ‘what do I do here? Should I get gas? Electric? Something to eat?’ But I went and got a carry-out and sat in the apartment with a candle lit.

“Two or three weeks later I was walking down the lane after training with a rucksack over my shoulder, boots in my hand… I’d been wearing the same clothes for weeks. I’d have gone a full week without a shower or a wash.

“One of the boys said to me ‘Domhnall, do you want a lift home?’ ‘Nah,’ I says, ‘I’m alright, I’ll dander’. But I didn’t have anywhere to go. By then I’d lost the apartment. I went down to The Rock, had a few pints, then it was closing up time… I’ll never forget standing there on the street thinking ‘what am I going to do now?’

“I’d been sofa-surfing for a while, but now I had nowhere to go. I lay beside a bus-stop for a couple of hours, and then I ended up walking up the Andytown Road to my granny’s. When she opened the door that morning she found me lying on her doorstep.

“She was very hurt, crying... devastated really. If I’d been honest, she’d have had me staying there, but by that stage I wasn’t being honest with anybody.”

Head boy, colleges’ Allstar, Antrim star in the making across both codes and here, at 22, homeless and hopeless – but not without help.

In tomorrow’s Irish News

“You’re climbing up walls but when the other option is to go back to the life you’re living and probably die, from somewhere you have to try and find the strength to see it through...”

It was only when he hit rock bottom that Domhnall Nugent really realised how much those around him cared. In part two, he tells Neil Loughran about the journey back to sobriety, and back to a sporting world he loved