ELEVEN months have passed in a blink of an eye since we last met at Mickey Harte’s home in Glencull, Co Tyrone.

It was a beautiful, bright day when the three-time All-Ireland winning manager announced he was stepping away from Tyrone.

Last Monday afternoon, it was another beautiful, bright day.

This meeting was quite different to our last. It was a surprise to learn Harte has published his third book, entitled ‘Devotion – A memoir’, ghost-written by journalist Brendan Coffey, which follows ‘Kicking Down Heaven’s Door’ (2003) and ‘Presence is the Only Thing’ (2009).

There is no grand book launch circuit planned around the country and no endless cycles of media interviews. One of the most fascinating figures in the GAA, you sense Harte is content to leave his latest archive that covers the last decade or more of his life with little or no fanfare.

But this is no ordinary memoir. Contained in the 312 pages is every conceivable emotion.

It is wonderfully lyrical, nostalgic, funny, dark, tragic, deeply emotional, honest and hopeful, with first-person accounts from Harte’s sons Mark, Mattie and Michael and John McAreavey on their unspeakable grief they endured and continue to endure following the death of Michaela while on honeymoon in Mauritius in January 2011.

Both Harte and Coffey capture the harrowing news as it was relayed to each family member. Brendan McAreavey rang Harte to say: ‘Something has happened to Michaela’ and advised him to ring John in Mauritius.

In the book, Harte says: “I got a number for the hotel in Mauritius. Somebody put me through to John. From the background noise, I could tell that the lobby was busy. ‘John, is there something happened there?’

“‘Aye, aye… Michaela’s died. Michaela is dead’. He handed the phone back to a member of the hotel staff.

‘Is she dead?’ I asked.

‘I’m afraid that’s the case.’

“John was hardly fit to speak. I could hear the distress in his voice. The distress is what I remember most…”

The book immediately goes into John McAreavey’s recollection of that terrible day.

“The news was breaking me,” writes Harte, “but the story of Michaela’s death was mine to tell. I had to carry the news to Marian and the boys.”

The subsequent accounts in the book from Mark, Mattie and Michael ram home the shock and sadness of their sister's death like it was yesterday...

We’re back in the little outhouse across the yard from the family home. Two chairs a couple of metres apart facing one another, a couple of treadmills pushed to one side of the small room and tea, coffee and biscuits within arm’s reach.

The book began as a series of conversations with the Maynooth-born writer back in 2017, who was friendly with one of Harte’s nephews.

Their chats would eventually be compiled into a book with the lofty hope they would coincide with a fourth All-Ireland title for Tyrone.

The Red Hands did clinch their fourth All-Ireland crown, only Harte was no longer manager.

“When the second book was done, which was an autobiography, I thought I’ll not be writing any more books,” Harte says with a wide smile.

“I met Brendan [Coffey] three or four years ago. We got chatting and he said about meeting up and doing a few more of these and I enjoyed meeting him anyway. I suppose the book has changed direction a few times. We thought this would be exclusively a football book and maybe not go into more sensitive things but we couldn’t talk about life and the last number of years without addressing the things that happened.

“I was probably hoping that it would coincide with another All-Ireland victory… Brendan interviewed our sons and John – the section of the book about Michaela’s death – and also introduced Tony [Donnelly] and Gavin [Devlin] who knew me as well.”

Huge swathes of the book revolve around the tragic events of Michaela’s death and how a father, mother, sons and brothers, a husband and extended family members grieved and survived the terrible aftermath.

And yet, through everything, you meet a man at his home on this bright Monday afternoon who is “mad about life”, who talks about his insatiable pursuit of justice and his admiration for Marian, his wife, his three sons, John; he wanders into the past and relives an idyllic childhood and remembers two Beech trees across from his house that never lost their leaves.

All the while he weaves through the years with Tyrone, and then leaving Tyrone, and how his account of what happened to young Paul McGirr never ceases to stop you in your tracks, the tensions with RTE, his cancer scare and watching Tyrone win this year’s All-Ireland without him at the helm.

He could be forgiven for feeling a little odd when he accepted an invitation to attend Tyrone's post-match celebrations at the Armagh City Hotel.

“I was glad to be invited to the event and I felt no stranger to it and felt comfortable to tell you the truth," he says.

“I didn’t anticipate that I was going to be asked up on stage to speak but it was a good opportunity to congratulate them and congratulate the management, which I did, and now the next generation have All-Ireland heroes that they can look to because a lot of the children wouldn’t remember the 'Noughties' men. That’s how fast time goes.”

Naturally, a big part of Harte feels he could have been in that hotel function room as manager of Tyrone having masterminded that elusive fourth All-Ireland crown.

If only he’d a fully-fit Paudie Hampsey over the past couple of seasons. Or if Darragh Canavan had emerged a year or two earlier.

What could have been achieved with Conor McKenna having another year under his belt with Tyrone.

And Cathal McShane’s return to fitness after serious injury and being his electric self in 2021. And ruing how Tyrone always ended up in Ballybofey.

“We never had those luxuries,” Harte says. “With Donegal, Michael Murphy never missed a penalty against us and he never got sent off and Neil McGee was never carried off.

“But the players seized that opportunity. When lady luck shines on you, she doesn’t actually say: ‘I’ll do the rest for you.’ She says: ‘There’s a bit of luck – so go and make use of it.’ They made use of those rub of the greens and that’s great.”

Towards the end of the book, Harte and Coffey capture his exit brilliantly as both manager and captain Mattie Donnelly sat in the Garvaghey car-park awaiting to be called into a meeting to address the management committee.

Ninety minutes the pair sat in the car-park but the invite never materialised.

Harte writes: “My fate was in the committee’s hands and, unknown to me, they were taking a vote. The split (6-5) went in my favour but I needed 60 per cent, one more ballot to get my wish [to stay on one more year].

“Finally, just after 11pm, some movement. Lights went low inside the building as the officers started filing out. One by one, they slipped away, headlamps leading them to the gate…”

During our hour-long interview, Harte’s phone pings with messages and rings.

Eleven months ago, any trace of bitterness of how his departure was handled was well hidden.

To this day, Harte prefers to be thankful for a managerial journey that lasted 30 years with his native county.

“I’m kind of a realist,” Harte says. “Things happen in certain ways and certain times. I still do believe that I’ve much more to be grateful for than I have to be annoyed about. Disappointment was the word I would use.

“I was disappointed and I still hold that; disappointed that it was seen as my last year and what was 30 years of service. I felt it wasn’t a fair way to end that; nobody could call that a year in football. I would love to have had a replacement year. That didn’t happen and obviously some people in committee made that the case and I have to accept that.

“It disappoints me but it’s not something that I’m going to be bitter about, that’s not the way I would describe it because I do believe I got so much out of those 30 years.”

Harte also goes into some depth of how relations with RTE became fractured and eventually broken beyond repair following a confidential letter from the-then Tyrone manager relating to the perceived side-lining of commentator and close friend Brian Carthy that was ‘leaked’ to a newspaper and later the “horrific skit” featuring the song ‘Pretty Little Girl from Omagh’, broadcast on The John Murray show, that “changed everything”.

“To play that song showed their complete lack of sensitivity,” Harte writes. “How crass can you be? Michaela was dead a mere matter of months.”

Harte rang the RTE host a few days later “calmly for the most part” and saying: ‘Do you even know me? Do you know anything about me or my life? Do you know what my life looks like right now?’

“I got up and walked past my daughter’s room, which hasn’t been touched since she was murdered.”

Harte rejects the notion that he was “having a crack” at RTE in his book.

“I’m telling the truth about what happened because that has been blurred in many ways since,” he says.

“It was case of ‘we’ll really tramp you into the ground for questioning our business’, so to speak…”

Tyrone’s RTE boycott endured throughout Harte’s reign as senior manager. Interview requests were always turned down.

Although Harte didn’t issue a ban on his players, he would have been disappointed had any of them spoken to the national broadcaster.

“I would have had to accept that,” he says now. “It wouldn’t have been my preference but I’d have to accept it. When enough of the players decided they wouldn’t do it, then the rest of them said they’d go with that as well. Once the major players decided they weren’t doing it, that was it then.”

Even at the start of the 2021 League season and with Harte wrong-footing everyone by taking the reins in Louth, he was miffed by the conversation on RTE’s The Sunday Game after his adopted county lost their opener to Antrim.

“That even continued on ‘til I went to Louth,” says Harte.

“In our first game, we lost by a point to Antrim and that night I’m “under pressure”. Under pressure? A person on that programme said I’m under pressure? When did they ever talk about Division Four at all?

“[But] it’s this subtle pressure that gets into people and then people start to believe it.”

In 2015, it was widely known Harte’s health was suffering. Bladder cancer. Luckily, it was detected early and after some surgical procedures and chemotherapy treatment he received the all-clear two years later.

“I’ve to thank Dr Damien O’Donnell for ever more because if I wasn’t with the team and with him I could have waited another few months because there was no apparent issue. I didn’t feel sick. It wasn’t painful going to the loo.”

Nevertheless, for most of 2015 the “outcome was uncertain”.

He describes their All-Ireland Qualifier with Tipperary in July of that year as “one of the worst days I went through with cancer”. He suffered searing pain across his back and vomited at the front of the team bus.

Still in bed a couple of hours before throw-in and assistant Gavin Devlin looking after things, Harte took a painkilling injection and somehow managed to stand on the side-line for the duration of the game.

A few days later, a stent was inserted between his kidney and bladder that solved the emerging issue.

Reflecting on his illness, he says: “You should really be thanking God every morning, and you should be saying, isn’t great to be able to do this and to face the new day with enthusiasm and energy – even if it’s wet or rainy, just say that we have this day, we have this day to live. It does make you appreciate life when you get hit with a thing like that and to be able survive it.”

Despite the pockmarked road Harte has travelled, there are moments of uproarious humour in the book. From their student days in Belfast, Harte and his former assistant Tony Donnelly have been best friends.

Harte never drank or smoked. Donnelly enjoyed both. But it never inhibited their friendship. Harte tells the story of how Donnelly joined a darts club and he would tag along with him to the various pubs for matches.

West Belfast, where the pair were studying, was a tense place to live in the 70s. One night, the pair were stopped by a British Army patrol.

“For some reason,” Harte writes, “I had Tony’s darts in my breast pocket.”

‘Give me those,’ the soldier demanded. ‘You’re carrying a dangerous weapon.’

‘They’re only darts,’ I protested.

“Tony spotted his opening: ‘Obviously you’ve seen him play.’

Another time when Brian McGuigan made a long-awaited return after nearly losing sight in one eye, the Ardboe man jogged onto the training pitch only for Donnelly to start waving at him and shouting: ‘Brian, Brian, we’re over here.’

Another moment of light relief was when a car flew past Harte on the main road near Ballygawley and Owen ‘Mugsy’ Mulligan ‘mooning’ out the window.

“A lot of people fail to realise that management is learning how to work with different personalities,” Harte writes.

“And you never know it all. To get the best out of ‘Mugsy’, I had to bend the rules. One size fits too few.”

While there is an abundance of football chat in the book, the early chapters are beautifully written, helped in no small part by Harte’s vivid recollections of his childhood.

“I’ve always great memories of my mother growing up, God rest her, and daddy, and the home that I grew up in. My mummy would have carried me down the stairs on her back and set me in front of the fire to get my breakfast ready, and she did that when I was six or seven years of age,” he says.

“She probably did that with all of us. I remember looking out the window and across the road there were two huge Beech trees and the leaves were always green on them.

“I don’t ever remember the leaves not being on them or the winter version of them. So that tells you something about my childhood. It was always secure. It was always good. It was always pleasant. It was just a great place to be and I thank God for mummy and daddy.

“Materially, we weren’t rich in any shape or form but, spiritually and lovingly, we were really rich, but it wasn’t an era you talked about it. You just felt it. It was same as the faith – you just caught it, it wasn’t pushed on us."

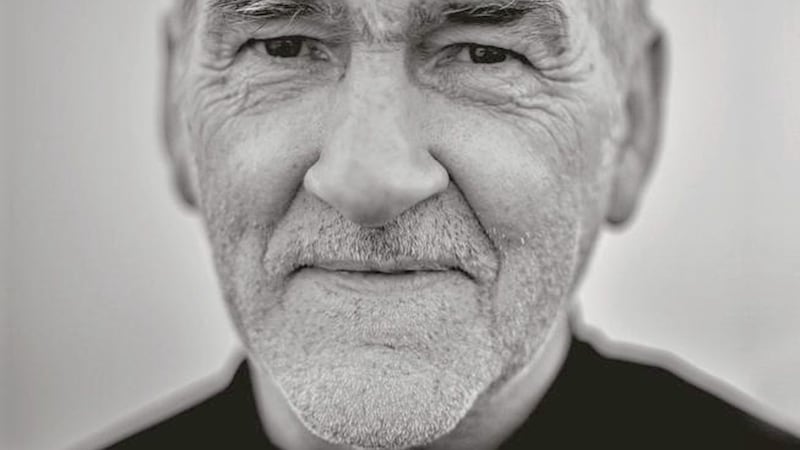

Mickey Harte is 67, but he doesn’t feel it.

“You come to a point where every stage of your life is great. I loved when we were young playing football and tearing about. I loved when we got married, I loved our children being born and I loved moving on when I couldn’t play football and our children growing up to be their own people. It’s just these phases of life that have their own unique gifts and then being a grandparent is a gift too.”

Harte adds: “I saw the love of Michaela towards her grandparents. They treated her like a wee princess, and I saw Michaela with Marian’s mother and father and she loved this wisdom of older people and the craic and stories that they told. And she’d hold her arms feeling her skin, and it was just lovely that she was connecting with her granny that way. And now we’re those grandparents.

“This relationship that I viewed Michaela having with her grandparents we have that with our wee grandchildren now. All these things and the life cycle is amazing. At the age I’m at it’s great to have lived and be well enough to enjoy all of those things.”

'Devotion – a memoir' by Mickey Harte, with Brendan Coffey, published by Harper Collins Ireland, Dublin. It is available in all good bookshops from today. Price UK£21.99.