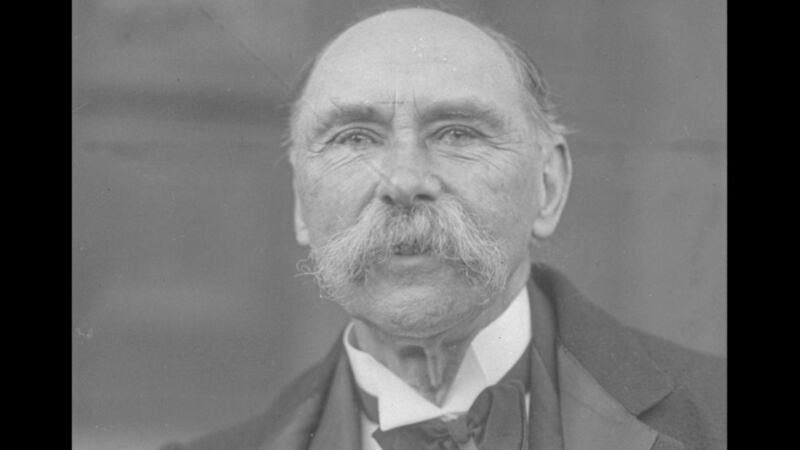

DOUGLAS Hyde was a contradiction.

A Protestant born in Roscommon in 1860, he resisted his father’s pull to follow him into the clergy and would instead devote his life to all the Irishness he could muster.

Mired in the world of politics, he did his best to be apolitical.

He was not, in the sense of the games themselves, a huge supporter of Gaelic football or hurling, but was central to helping the GAA further their nationalist ideals.

What the Irish Republic’s first ever president did was help keep alive a sense of national identity that was being crushed beneath the weight of Anglicisation.

Few, if any in history, did more to re-establish the Irish language. He was a founding member and the first president of the Gaelic League, which fought for the preservation of the native tongue.

This was a man who could converse in seven different languages, but famously said “I dream in Irish”.

He made a young friend in Michael Cusack when they both attended Trinity and as Cusack helped lay the foundations of the GAA, their organisations were joined at the hip.

Forty years later, having given his whole life’s work over to promoting the national identity, Douglas Hyde found himself at the heart of a controversy he didn’t court, that he knew was coming, but that he wouldn’t shift his principles to avoid.

It would result in the GAA banning the first President of Ireland, and a man who had held a patronage of the association since 1902, from any involvement for virtually his entire term of office, which ran from 1938 until 1945.

His story is brilliantly told in Cormac Moore’s book, The GAA v Douglas Hyde.

Hyde’s ‘crime’ was to have accepted the FAI’s invitation to attend a soccer match.

As Ireland and Poland took the pitch in Dalymont Park, Hyde and Eamon de Valera were presented and given a standing ovation by the record 34,000 crowd.

The president knew what was coming when he accepted the invitation, but he saw his role as being all things to all Irishmen and women.

The newspapers had spent the week speculating over what action the GAA would take on a man perceived to be one of their own.

The answer would follow quickly. Led by their leadership of Armagh-born Padraig MacNamee and Padraig Ó Caoimh, like Hyde a Roscommon native but a man more associated with Cork, they banned him and stripped him of his patronage.

Only a handful of people had ever been given a GAA patronage before Hyde was bestowed with his in 1902 - at the same meeting as The Ban’s most rigid interpretation had been implemented.

First introduced in 1885, it dipped in and out of the rulebook in various guises until 1905. Three years earlier, the introduction of ‘vigilance committees’ in each county was seen as a significant step.

These were, in effect, groups of men sent to spy on their own.

The Ban grew and grew. Initially restricted to the playing of games, GAA members were no longer allowed to spectate at ‘foreign games’ from 1908. Magistrates were banned from GAA involvement in 1918, then civil servants in 1919.

It was the seemingly crazy ban on attending ‘foreign dances’ that came into being in 1932 which would go a long way, in time, to the dissolution of the whole idea.

But that would take another four decades.

By that time, Douglas Hyde had been dead for more than 20 years. He was 78 when he took office, and spent the last five years of it wheelchair-bound after suffering a stroke in April 1940.

He died on July 12, 1949.

It was in the six counties that the zealousness for upholding his ban largely came. The other three provinces were divided but with the exception of west Tyrone, virtually the whole rest of the north backed the GAA.

That was unsurprising and very much of its time, given how much harder northern nationalists were having to work to retain their sense of Irishness.

Hyde was criticised at meetings in Armagh and Derry. This was around the time that a bomb in Brantry (Eglish) destroyed the clubhouse a week before its official opening, and police tore down goalposts before the inaugural game of the newly-founded RGU Downpatrick.

Dublin Castle, home of the British establishment until 1922, had never acknowledged the ban until they tried to implement a tax on sport in 1917. The GAA refused to pay and were told that if they dropped The Ban, the tax could be waived.

They still didn’t pay, and what they got in return was an admission from the British that their rulebook contained a weapon against the neighbouring occupant force.

Its application could be liberal in places over the 66 years it remained in permanent existence.

Equally, it was against the backdrop of several high-profile instances that the GAA felt their hands were tied by Hyde’s presence at the soccer match.

Garda George Ormsby, a great Mayo player, was banned by Sligo county board after attending a soccer match in February 1938. He had been on duty that day and Connacht Council subsequently reinstated him. That move suggested the GAA would allow members to attend foreign games in an official capacity, something it would then contradict with Hyde.

That same summer, Tipperary hurler James Cooney played in the Munster championship against Clare, believing his three-month ban for attending a rugby game had expired. In a typically GAA-way, it had, but he fell down on a technicality. Clare were awarded the game and Tipperary’s reign as All-Ireland champions was ended.

At the time, the Gaelic League had a similar ban in place. It voted to remove it in 1938, but the move greatly angered the GAA. The ban was quickly reinstated amid great pressure from the sporting body.

So there was all this fuss throughout the year that meant when Douglas Hyde attended a soccer match, the GAA risked being branded as hypocritical if it did not act, yet were going against the George Ormsby case in doing so.

Hyde was removed as a patron and banned from the GAA.

When Kildare put a motion to the following April’s Congress, it was voted on without debate. The Irish president’s ban was upheld by a vote of 120-11.

The GAA didn’t invite Douglas Hyde to an All-Ireland final again. He left the office of president in 1945 having not attended another GAA event. He died not having been reinstated.

The Roscommon man missed out on his native county’s back-to-back All-Ireland titles in 1943 and ’44.

He paid £1 into their training fund in 1939 and ’41, but took his thoughts about the ban the GAA imposed to the grave with him.

Eamon de Valera met with the GAA upon the seating of Hyde’s predecessor Sean T O’Kelly and relations were smoothed out.

The whole issue had festered and the two sides became like the friends who fell out and were both too stubborn to admit their fault, so went on not speaking.

The Ban would continue to dominate GAA discussion for years but it was 1971 before Congress in Belfast finally, against the wishes of only Antrim and Sligo, voted to remove The Ban.

In the same year, Roscommon county board renamed their grounds as Dr Hyde Park.

The GAA’s centenary celebrations in 1984 marked his contribution when then-president Paddy Buggy laid a plaque on Douglas Hyde’s grave.

It was like the slowest of admissions that banning an Irish president who had done so much to promote their causes was cruelly unjust.