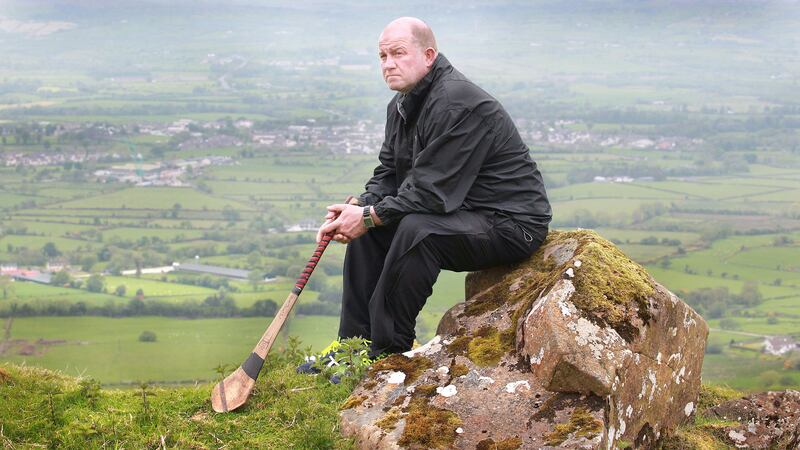

GEOFFREY McGonigle shuffles excitedly at the memory, a mischievous smile playing across a face still instantly recognisable to followers of football and hurling through the Nineties and Noughties.

The conversation has moved to the Ulster final of 20 years ago, the last time Derry lifted the Anglo-Celt.

Already McGonigle has covered his love affair with both codes from the earliest of days, the boy wonder years, county call-ups, county fall-outs, minutes here, minutes there, tipping the scales, scaling the heights, frustration, elation and cult hero status.

The language has been colourful, occasionally industrial and always to the point as stories and experiences are relived, the emotions of bygone days seldom far from the surface.

Yet it is with mock politeness that the reluctant super-sub recounts his most celebrated cameo with the Derry footballers, coming off the bench in 1998 to make a late, Ulster title-winning contribution; a contribution that owed much to a subtle/blatant nudge - delete according to allegiance - on Donegal defender Noel McGinley.

“Excuse me,” he says in as genteel a fashion as possible in that brusque Dungiven brogue, cupping those vice-like hands into semi-circles around an imaginary size five, “that’s my ball”.

McGonigle had only entered the fray minutes earlier with the scoreboard reading 0-7 apiece on a wet, windswept day at St Tiernach’s Park, the north-west rivals seemingly on course to do it all again following a turgid affair.

Watching from the bench wasn’t something McGonigle ever got used to, and he paced the line like a bull in a pen, 16-stones squeezed into his 5”11 frame, a logic-defying mix of brute power and deceptive pace woven together by hand-eye wizardry and the balance of a ballet dancer.

Every second of his warm-up there are ripples of anticipation among the assembled hordes in red and white, one of whom was McGonigle’s father Mickey, a figure so vocal he was once described to me as “the kind of boy who would try to eat his way through the fence”.

“Ohhhhhh what...” smiles the son, rolling his eyes to the heavens.

“Heart on the sleeve job, oh aye. People always wonder where I got my madness from. The apple doesn’t fall far from the tree.”

McGonigle’s eventual arrival is received, typically, with the most guttural of roars. And, less than a minute into added time, he had a major hand in deciding the outcome of the match.

Joe Brolly has since written that one of his club-mate’s greatest assets was “an arse like a bag of cement”. He was never so glad of it as that day.

“I mind [Anthony] Tohill looked up and he just thumped it in my direction,” he recalls.

“The man was standing underneath it and I just nudged him with my ass, caught it and Brolly was coming down the other side…”

After dislodging McGinley, McGonigle broke the ball and charged forward before playing an inch-perfect hand pass to Brolly, wide open on the left. He made no mistake, calmly rounding Tony Blake before sending kisses to the crowd.

They may have been in Clones but it was a goal crafted at O’Cahan Park, the builder and the barrister combining to devastating effect as they had done so many times in the black and white of club.

Geoffrey McGonigle won’t be at Celtic Park for tomorrow’s renewal of acquaintances with Donegal two decades on. He has no truck with the class of 2018, or Damian McErlain, and wishes them only the best.

It’s just, well, modern football does little for him. Too much focus on defence and systems, not enough flair or freedom. Do you see where he’s going here?

They just don’t make them like they used to.

****************************************************

HE may have got his competitive edge from the old man, but it was Jean McGonigle who kept driving him back to the field. Small ball, big ball, it didn’t matter, she could see that the young Geoffrey had a talent to be nurtured.

“My mother pushed me all the time,” recalls the fifth of eight children in the house.

“She’s maybe my biggest fan, biggest critic too. She was the same with all of us. In our house there’s bags upon bags of scrapbooks. Aw, she’s lethal.

“We have a big plaque at the house, my father got it made years ago, and every medal I’ve won since is still on it. Unreal. Every medal you won you had to take it out of the house because she had to put it up on the board. Swear to God.”

And any time Jean heard another son Michael getting his gear ready, she pushed Geoffrey again – out through the back door with his brother.

“I used to annoy Michael.

“My mother would kick me out to go along with him and he used to kick me in the hole and send me back home. Then when I went home my mother would send me out back after him again.

“He’s five years older than me, he hurled for Derry minors, and I just hung on his shirt tail - I stuck to him.

“Big Liam Hinphey was the manager and he loved to see me coming because I’d gather all the balls up. Liam’s another madman, another boy with the heart on the sleeve. Whatever’s in him’s out of him. Lethal character; just a legend around our place.

“That’s what started the whole thing …”

Eventually Michael relented and, in the long driveway at the side of their house, the brothers would puck about and kick ball until day became night.

“I used to get the hurling ball and just wail it against the wall. All just first touch stuff. Many a broken window I put through. I got my head skelped for it manys a time.

“Then Michael would come out and drive the ball at you as if he wanted to kill you! You did the same to him, and that’s the way we were brought up. To be competitive.

“We used to play matches in the garden, my da used to play and everything… aw, they were killing matches! Lethal, but it was a bit of craic.”

Soon word began to spread as those skills honed in the drive transferred to the field, and an educational switch to St Patrick’s College, Maghera – four-time MacRory Cup-winners by then - provided the ultimate acid test.

Adrian McGuckin has helped build a tradition of footballing excellence at St Pat’s through the decades as the school provided a conveyor belt of future county stars.

And he remembers first clocking eyes on the stocky boy from Dungiven with a wand of a left foot.

“Geoffrey came into our school in fourth year and he was just such a naturally gifted footballer – probably one of the most complete talents I’ve seen or met at that age group,” he said.

“People talk about the Mikey Sheehy chip-ups, every ball that came to Geoffrey he chipped up off the ground. That was in the ’90s in colleges football where every match you played you were mucked up to the eyeballs, and they nearly all came up clean.

“He was flamboyant, the sort of boy that, whenever you were going to see a game, you were going to come away with something to talk about, whether it was a tremendous score or pass, an outrageous dummy.

“He was just a magical talent, a complete one-off.”

In 1990 a 15-year-old McGonigle helped the school defend the Hogan Cup, and McGuckin can still see him landing “an impossible free-kick” near the end of that replay win over St Jarlath's, Tuam.

But the protégé talk, the swelling buzz inside the county, it all washed over.

“I just went out and played, I didn’t care,” he insists.

“See every game you played, it was a bonus because you weren’t sitting on a bench or sitting in a bar. I was kept level-headed, there was a tight rein at the house.”

Already a star with the Derry minors, banging over big totals for Dungiven week in, week out, a huge future looked on the cards in both codes. So it proved in hurling, where he was a talismanic figure until the mid-Noughties, hanging full-backs out to dry until his legs could play no more.

But the football? On that front there were more weighty issues at play.

****************************************************

“I was on the panel for six weeks at the very start but I wasn’t getting any football or hurling, I was getting playing nothing. I was 18 and I was missing out on a wild lot of matches, and I thought to myself naw, I’m too young for this”

IN 1993 Eamonn Coleman’s Derry side, a perfect amalgam of hard edge, cunning and craft, walked the steps of the Hogan Stand, Sam in hand. Geoffrey McGonigle, in theory at least, could have been among them.

The reality, though, was completely different. Watching on from the sideline with little or no chance of getting a game came as a shock to the system. Even now, in his mind, there was only one option open.

“I never was used to sitting down and looking at Dungiven playing so I quit, but I don’t regret it,” says McGonigle 25 years on.

“I was only 18. I came back in then in ’94 but still I’d to wait a long time to get a start. Sure you’d Brolly, you’d [Enda] Gormley, you’d Declan Bateson all ahead of me, Eamonn Burns…

“I hated it, sitting on the bench, wailing away. It never mattered in the hurling, but in the football boys always said I was too heavy or I wasn’t fit enough.”

Opportunities came and went, and a gilt-edged goal chance in the dying minutes of Derry’s 1995 Ulster semi-final with Tyrone still nags.

“That day I hit the f**king post,” says McGonigle, eyes rolling once more.

“I’ll never forget it. I was one-on-one with big Finbar McConnell, it hit the post and went out, straight between Gormley’s legs. Jesus Christ if it had hit Gormley at all the ball would’ve been in.

“I got some stick for that. They went on and got to an All-Ireland final. That could’ve been the start of it.”

As it was McGonigle would spend the next number of years in and out of the panel, a feeling growing that, no matter what he did, it would never quite be good enough.

Talk about his weight was always on the tip of tongues too. Every week it seemed that stories would circulate about missed training sessions, while alleged sightings of McGonigle in this chipper or other had a way of making their way back to Coleman.

In a football-mad county like Derry, stories spread like wildfire. Some were true, some exaggerated versions of the truth, others downright lies.

“I got used to the talk. It probably annoyed my mother a bit alright.

“But nowadays, county players can’t do the job I do in construction. They can’t work on a building site because it kills them. Boys down the years, very good players for Derry, all worked on the site - Tony Scullion, Kieran McKeever, Brian McGilligan.”

McGonigle went on a nutron diet at one point, shedding almost three stone. And while there were obvious physical benefits, there was one significant drawback.

“I couldn’t put the ball over from 30 yards!” he smiles ruefully.

“I’d no strength. I’d all the pace but I couldn’t kick the ball the way I did. At that time there were no big weights programmes. I wasn’t a man for sitting in a gym pumping weights.

“I was strong enough anyway, I didn’t need any weights. I mind John Morrison saying to me ‘I know you don’t need weights, you need running’.

“There used to be three groups all the time - one went out, one did weights and one did circuits. I went out and did the running first, came in and did the circuits, then back out and did more running. I never did the weights.”

And when things were going well, when McGonigle was shooting the lights out either from the start or from the bench, everybody wanted a piece of him. There was nobody else quite like ‘Big Geoffrey’.

But the glare of the media spotlight didn’t float his boat.

“I mind at Casement after we won a game in the Ulster Championship I was sitting in the changing room smoking a cigarette, like I normally did.

“Next thing about five boys bounced through the door looking to do interviews and I said ‘boys, go on away to f**k ’til I finish this fag’. I was just pure relaxed after the match.

“I mind going out to them, five minutes and away. I hated doing them. I wasn’t interested in that. It was more Joe’s thing so I just let him at it.”

And, after the 1998 Ulster final, both Brolly and McGonigle would find themselves in demand once more.

****************************************************

“McGonigle’s in here and McGonigle’s got a chance here, he’s got a man inside…

and it’s Brolly, here it is for Derry…

and Derry may well have won the Ulster Championship…”

JOE Brolly did well not to hit the rain-lashed sod below as a shaven-headed figure bearing the number 22 across his broad back bounded into view and threw his right arm around the goalscorer, the left fist pumping furiously in red-faced delight.

Ger Canning’s acceleration through the octaves perfectly captured a moment of high drama on a day of low quality illuminated by a burst of brilliance.

McGonigle has never watched that moment back. That’s not how he operated. Once the game was over, joy or disappointment eventually fizzled out and was put aside.

The night after scoring 1-2 against Cavan in a 2000 Ulster Championship match, he was playing midfield for Dungiven in a Dr Kerlin Cup match.

Nowadays McGonigle coaches the club’s senior hurlers and camogs. He is happy with his lot and the years of joy banked from both codes, even the days when he was bouncing up and down in a rage or driving his hurl into the turf.

There is still time for one last reminiscence though, about that final, and that goal, and the last word on the man who has filled so many column inches through the years extolling the virtues of his Dungiven club-mate.

“If it had’ve been the other way about,” begins McGonigle, now 43, a half laugh as he thinks back to that moment in added time, “I wouldn’t have got a look in. He’d have stuck it over the bar.”

Luckily it was Geoffrey with the nudge in the nick of time. The rest, as they say, is history.