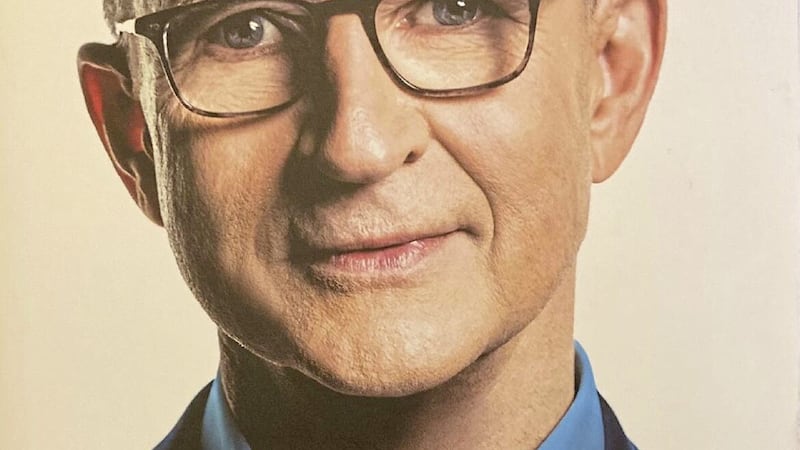

Following the publication of his autobiography ‘On Days Like These, former Republic of Ireland and Celtic manager Martin O’Neill talks to Brendan Crossan about a tumultuous and hugely successful life in football…

Brendan Crossan: How long did it take you to write your autobiography?

Martin O’Neill: I started to fidget with it early on, my first day leaving Belfast and becoming a professional player and it grew from there. So I would say it probably took around six months. I’d written a lot of it in long hand but then found out there were much easier ways to do it! I just felt putting it down in long hand I could almost hear my own voice in the writing.

BC: Not a lot of people write their own books these days…

MO’N: That is true. I wanted to do it myself. I’ve been offered a number of times for ghost-written things and then I found out that some ex-players don’t even read their own autobiographies, so to write it myself, at least I achieved that. I suppose there was some sort of cathartic aspect attached to it all as well.

BC: There are some beautifully written passages in the book. Which part of the book did you enjoy writing about most?

MO’N: Being a footballer, I think moving from Distillery while being a student at Queen’s University to my first day ever as a professional footballer way back in late 1971. I can remember that like it was yesterday and I remember Brian Clough coming in 1975, so those things I can definitely remember without a problem. Growing up that’s what I wanted to be – a professional footballer playing in the English League, so I really enjoyed writing that part.

BC: I was proud to say Jimmy McAlinden, the former Belfast Celtic great and FA Cup winner with Portsmouth, was a neighbour of ours growing up. In your book, you tell the story about how Jimmy helped get your first contract in England sorted out. He seemed to be a mentor of sorts…

MO’N: Absolutely. Not only that, when I came to Distillery, I played about five or six reserve games and while there was an improvement in each of the games, I was still a far-cry from being in the first team.

But Jimmy threw me into the first team at Portadown. I can’t ever repay him. I scored a goal and we won 3-2. Whether I deserved to be in the first team or not is another question but he’d decided that it was time. And I never really looked back. Jimmy was very, very astute, almost a mentor to me in that year.

BC: I expected to read more about your Republic of Ireland managerial career in the book as you spent five years with them. Is that a reflection of you not enjoying it as much as you’d hoped?

MO’N: My 19 games with Nottingham Forest doesn't even get a mention in the book that came after the Republic of Ireland job. I probably didn’t anticipate the Ireland part of the book to be as short, not at all. And I’ll take note of that. But I absolutely loved it. It was a privilege managing the team, it was great and, of course, we had the success in France in 2016…

In my mind and in my dreams I wanted to re-live – or try at least to emulate the success that Jack Charlton had. When we opened up in Paris against Sweden we saw over 20,000 Irish fans in full voice, I thought, this is really what it’s all about.

Jack Charlton’s success was absolutely phenomenal, and at least we touched part of that with Robbie Brady’s goal against Italy which is talked about as much as Shane Long’s goal against Germany...

Listen, the truth is this, as you’d well know, I didn’t really get on too well with the Irish media and they didn’t really get on with me, so we never really hit it off in any aspect. And that was obviously – what shall I say – exacerbated by our defeat to Denmark and the hammering we took, even though that was a play-off game to try and qualify for the 2018 World Cup. I thought: Is that a sackable offence? In fairness, I think I could have handled the press interviews a bit better than I did.

BC: There was an adversarial nature to your media relations and I'm sure the media weren't blameless. How could you have handled things better?

MO’N: I think I should’ve taken a little bit more time out. You’re being interviewed immediately after a game, either a win or a loss. When you win, it’s not a problem. Of course, when you lose, you accept the criticism – absolutely. But after Denmark it was really disappointing especially having drawn in Copenhagen [in the first leg].

To be well beaten in Dublin, it seemed from this distance anyway, that it was a moment they were waiting for. And after that it was kind of downhill.

I could've taken an extra minute or two to say to a reporter: ‘By the way, this is actually a play-off game for the World Cup and we were fourth seeds in the group.’ It mightn’t feel as bad today to be beaten at home by Denmark. Maybe we should reflect a little bit on how well the team had done. Listen, hindsight is a wonderful thing.

BC: With Ireland, you had a quite limited squad but you can’t come out and say: ‘Well, we’re not very good, are we?’

MO’N: Seamus Coleman might have been the only player playing in the Premier League at the time. There were a lot of Championship players playing in the side and therefore the most important job was to actually motivate players to play as strongly as possible for as long as possible over the 90 minutes to actually overcome obstacles – obstacles of playing better teams. Just qualifying for the Euros in 2016 is something that I cherish.

My remit was not to cure the ills of the League of Ireland or anything like that. My job was pure and simple – qualify for the Euros. Then, after that, if you’re going to be around, then of course you can oversee the whole shebang. I had umpteen meetings with the boys taking the underage teams and I took a big interest, but that gets lost in translation.

But, overall, to lose to Denmark was majorly disappointing and we went into a Nations League which was essentially glorified friendly games. Way back then nobody knew the rules and in actual fact I don’t think they know the rules now. Michael O’Neill of the north had the right approach from the outset, in that these games weren’t important.

That was Michael’s approach and the Northern Ireland fans accepted that, and the Northern Irish press, more importantly, accepted that.

BC: Was Roy Keane high maintenance for you as Ireland manager? I remember he launched his book on the eve of an international match and he had his differences with Jonathan Walters and Harry Arter?

MO’N: Well, Roy is going to be big news one way or the other. His arguments with Walters and Harry Arter, you knew somewhere along the way those things would leak out and they’d become news, particularly with Stephen Ward and the WhatsApp message.

These things became magnified because it was Roy. I thought we’d be able to keep them in-house. There are very few football teams that I’ve been involved in that you didn’t have arguments or I didn’t have arguments with somebody.

But once Roy was involved, they were going to hit the headlines. I never thought them as being major, major incidents. I always thought we could quell them at the end of the day.

But, if you don’t follow up with a victory, then of course people will be saying: ‘Ah, there is tension in the room’. I think if you spoke to the likes of Robbie Brady and Jeff Hendrick who would say, at this minute, their best days in football were actually with the Republic of Ireland in the Euros.

BC: You write glowingly about your Celtic days and just how good Lobo Moravick was.

MO’N: You mention Moravick who was the best two-footed player I’ve ever worked with, no doubt. He was about 33-years-of-age when I came to the football club; I wish he was 26 or 27. He’d left us by the time we got to the Uefa Cup final [against Porto] but he would have conjured something in that final of 2003 if he was 26 or 27 rather than 33 or 34.

BC: Where were you happiest in your career?

MO’N: At club level, I found great happiness in all the places I’ve been. For instance, the players at Wycombe Wanderers gave me the opportunity to manage at a higher level. They put their heart and soul into the games, so I owe them a lot. I’d a great time there as my children were just growing up. Leicester City, after a really tough start, turned out terrific, I loved the club. Celtic, of course, was great. And then we’d three top six finishes at Aston Villa. You talk about regrets.

I wish I hadn’t fallen out with Robert Chase at Norwich because I’d two spells as a player there, very short spells, and a short spell as manager. So Norwich City will always be dear to my heart. Celtic, of course, was great and my wife says Glasgow was her favourite place.

BC: There’s a fascinating passage in the book between you and Billy Bingham where he makes you Northern Ireland captain, the nuances of which weren’t lost on either of you as you were a Catholic from Derry going to lead the team. Billy Bingham said to you: ‘No-one will care if we’re winning matches…’

MO’N: I owe Billy a great deal. For an easier life, he could have ignored me but my experiences at that time with Nottingham Forest, playing in Europe, he obviously thought I was a decent enough communicator. He knew he would probably take some criticism for it and he went with it. And, that’s right, his words were: ‘It will pass when we’re winning football games’. So it was a brave decision.

BC: In a parallel universe, if you hadn’t made it across the water, you might have had a long GAA career with Derry. There’s a passage in the book where you explain going to the 1958 All-Ireland final between Derry and Dublin and you’re there to see your brother Leo play…

MO’N: If I hadn't the opportunity to go across the water and play professional football, I’m quite sure that I would have played for Derry. Who knows? We might have won an Ulster title and gone on to win an All-Ireland. When Derry did win it in ’93, there was a real tinge of envy for those lads who’d done it. They brought the Sam Maguire Cup up to Derry and that was a big moment. Playing for Derry would have been a big highlight for me.

BC: I read an article during Euro 2016 where you said losing the 1970 Hogan Cup final felt as bad as losing the Uefa Cup final with Celtic in ’03. That statement really delves into your DNA, that Gaelic thread in you and how much it meant in your formative years.

MO’N: Absolutely. First of all, for St Malachy’s to win the Hogan Cup would have been fantastic because we’d a really good side and we should have won that game [against Coláiste Chríost Rí of Cork] by a distance and didn’t. The realisation for me was you had to win, and these hard-luck stories don’t count at all. You have to win. We didn’t win in Croke Park and we didn’t win in Seville and they really gnaw away at you.

BC: Have you ever watched a re-run of Celtic’s 2003 Uefa Cup final against Porto?

MO’N: No, I wouldn’t. I saw it on the TV a couple of years ago. It must have been highlights and they were into extra-time and I just switched it off. Somebody said to me: ‘Do you want to see the highlights of Vitor Baia going down with an injury?’ That’s all too clear on the day. I don’t need a TV to remind me of it.

BC: How good was Henrik Larsson? After Celtic he went on to prove his worth at Barcelona and Manchester United. Do you think he got better with age?

MO’N: I think that’s spot on because there was always a question of him playing up in Scotland and he could only do it there. Henrik Larsson, among some phenomenal games he played for Celtic, was fantastic in the Uefa Cup final against Porto.

He was a really great player, very brave and could score you a goal. He goes to Barcelona and helps turn the 2006 Champions League final [against Arsenal] when he comes on and then in the twilight of his career he goes and scores goals for Manchester United. I think all of those things prove that he could play at the highest level.

BC: You say you’re addicted to football but it’s a profession that often lacks loyalty…

MO’N: I think money has really changed football in many aspects. In my footballing days, players had no power whatsoever – and that was wrong. Now players have all the power – and that’s wrong. So there has to be a happy medium somewhere along the way. I do not begrudge the great players getting any amount of money that they get – Messi and Ronaldo – because they get people to go to the stadium to watch them. If you’re talking about younger players earning money and then feeling a sense of entitlement, I think that kind of thing disturbs people because it’s not really earned.

BC: Is there still a chance you could manage again?

MO’N: I certainly wouldn’t dismiss it. I think there is perhaps ageism in the game. There is no such thing as a perfect job. I do not have anybody working for me, so you have to get yourself out there and I’ve perhaps hidden behind COVID for the last couple of years. If an opportunity came along and they were asking me to do it, I would have to give it serious thought.

BC: Do you keep in touch with Roy Keane?

MO’N: Yes, I do occasionally. Luckily, we didn’t work every single day together! He’s doing really fine in the punditry world and he’s travelling out to the World Cup. I’d maybe keep in touch with him once a month.

Martin O’Neill will be in Belfast tonight to talk about his career at an event being held at the Europa Hotel, 7pm. Tickets, which include a signed copy of Martin’s autobiography, available from No Alibis Bookstore: https://noalibis.com/event/an-evening-with-martin-oneill-in-conversation-book-launch/