OUTSIDE the Royal Victoria Hospital, pacing up and down against a backdrop of smokers’ coughs and the whirring of automatic doors, Jim Magilton presses the phone tight to his ear.

It’s April 22, 2009 and his mother Maureen is in intensive care. Football should be the furthest thing from his mind, but relations between club management and personal circumstance are often strained.

On the other end of the line is Ipswich chairman Marcus Evans telling him that, after three years, it’s over. By now a part of the Portman Road fabric, player and boss, Magilton is scrambling for the right words.

A 14th place Championship finish in his first year had been followed up with eighth. Ipswich Town had missed out on the play-offs by a solitary point, but progress was clear to see.

And, after struggling to find his way in the early days, Magilton now felt in control.

Read part one of our interview with Jim Magilton

“As a player, it’s just about you. Once you become a manager, it’s about everybody. That was a steep learning curve.

“My first year and a half I was still probably seeing through the eyes of a player, instead of having that experience of thinking why somebody might be doing something.

“Three years into the job, I was so much better. I was in a position where I was loving going into work in the morning, I knew exactly what was happening in the medical room, from a coaching point of view. I knew where I was with the chairman, I knew I could manage up and rely on these guys to deliver.”

When promotion eluded them again, though, the wind of change began to howl ever louder.

“There was a takeover, a new owner, a different relationship. Board meetings had always run smoothly – now I was talking to Marcus on a screen. The dynamic changed.

“After three years, I knew that cycle of players wasn’t going to take us to the next level; I knew we needed the next level of player. And he just didn’t go with me.”

In Magilton’s final game, Ipswich beat arch rivals Norwich. To this day, almost any time he posts a tweet, there is a flurry of replies from Tractor Boys die-hards begging him to return.

But even derby day delight couldn’t save him. Without his knowledge, a press conference to unveil the new man had already been arranged.

“I had come home on the Tuesday night because mum wasn’t well. When I got speaking to Marcus the next day, the phone call lasted three minutes; Roy Keane was coming in.

“When you get a phone call like that, you know what’s happening.”

Still in a daze, he walked into the Royal and got the lift back up to the ward where dad Jimmy is sitting at his wife’s bedside. There’s a TV in the far corner showing Sky Sports News, the familiar yellow ticker bar flashing across the bottom of the screen.

‘MAGILTON SACKED BY IPSWICH’

“There was just silence for a couple of seconds, but I could see the guy in the bed beside mum looking over at me, then up at the TV. Eventually he turns round and says ‘you’ve had some day, haven’t you?’

“I burst out laughing - what else could you do?”

There would be no well-wishing call to Keane though, the pair having had an exchange of opinions, to put it politely, over a player transfer when the Cork man was in charge at Sunderland.

“He gave me a little slot in his second book,” grins Magilton.

He did indeed, across pages 222 and 223 to be precise.

Ipswich already had a manager at this time, Jim Magilton. I was being touted for a job that was already occupied. But I didn’t feel too bad about that. It’s not good, but it’s standard practice. I thought it was all right to chat about the job, I hadn’t agreed to take it.

I didn’t feel too sorry for Jim Magilton. I felt he’d let me down with a player when I was managing Sunderland. He was supposed to take Tommy Miller off me. We’d agreed a deal. The transfer deadline came, but Ipswich pulled out of the deal.

I rang Jim Magilton. I said ‘what’s happening? I’ve turned down other deals for Tommy because you said he was going to you’. He was proper aggressive; he didn’t give a f**k. It was all ‘f**k you’, and me back to him, ‘f**k you, you’re a f**kin’ joke’. But it started at his end.

So, part of my thinking was, f**k’m. It’s part of the business.

“He said to me and I reacted, then there was a war of words.

“When I read that, I laughed it off. He was a rookie manager, I was a rookie manager - just one of those things. Storm in a teacup.”

For all Magilton’s joviality, however, what happened next remains a point of considerable contention.

Offered the QPR job two months after his Ipswich exit, he canvassed the opinions of those closest to him. They were split down the middle.

Loftus Road had been a revolving door for managers since Italian multi-millionaire Flavio Briatore took ownership of the club. But with a deep and talented squad, and a pool of money to play with, this felt like a risk worth taking.

“It was probably the west Belfast in me,” he says, “just thinking ‘I’m going to turn this around’.”

After a slow start, a mid-October surge had them pushing into the promotion places before their form tailed off. In the aftermath of a defeat to Watford in early December, midfielder Akos Buzsaky claimed his manager had head-butted him in the midst of a heated confrontation.

Magilton was suspended by the club pending an internal investigation. His assistant John Gorman and first team coach Keith Ryan turned down offers to take charge of the first team unless he was reinstated.

Back home, his mum had been readmitted to hospital. Within a week, Magilton and QPR had parted ways for good.

“Never touched, never touched…” he says of the incident.

“It was a horrendous situation, horrendous allegations, completely unfounded. It was a witch-hunt.

“The lad in question, two weeks before that he came to me, very emotional about his father. I told him to go home - family’s everything. His father was over the moon we had allowed him to go home. People don’t see that side of it.

“I had to leave, but it was a learning curve, an unbelievable experience. After that, I had some time out. Mum passed away in February and I took a break for first time since I was 16.

“Then Michael asked me to help at Shamrock Rovers.”

***************

FRIENDS from their teenage years, Jim Magilton always knew Michael O’Neill was something special. With a ball at his feet, he was poetry in motion. But with a group of players at his disposal, he had the ability to work wonders.

In his second season at Tallaght Stadium, O’Neill led Rovers to a first title in 16 years before becoming the first League of Ireland manager to reach the group stages of a European competition when Rovers defeated Partizan Belgrade in the play-off round of the 2011/2012 Europa League.

“We had an unbelievable run - fairytale stuff.

“I loved working with Michael and you could see then the manager he is now. He was very meticulous, good with the players, open and honest, a great communicator. He could transfer a Powerpoint presentation into a practical breakdown on the pitch that the players understood – that’s the hardest thing to do.”

When Nigel Worthington stepped down as Northern Ireland boss in 2011, Magilton was the early front-runner, only for the IFA to head-hunt O’Neill. It was a situation that had the potential to prove problematic on a personal level, but the pair remain tightly bonded to this day.

“It wasn’t awkward,” insists Magilton.

“Michael came out of the blue; it was me and Iain Dowie. The talk was Michael was going to sign a new contract at Shamrock Rovers, but the IFA contacted him and asked him to interview, which was absolutely fine.

“When it was announced, I had already spoken to Melbourne Victory and the day after [club director] Ian McLeod rang me to see was I interested in becoming manager. I flew out a few days later and was sitting in the stand that Saturday night.”

Adventure called, but it took three months for Magilton to realise Australia wasn’t the place for him. The sporting epicentre of the country, soccer lagged well behind Aussie Rules, rugby and cricket in the affections of the Melbourne public.

Magilton turned down the offer of a three-year contract to return home. A stint in Qatar working as a pundit on TV station Al Kass opened his eyes not just to the local league, but also provided a worm’s eye view of how the world’s best club sides prepare during regular off-season retreats at the Aspire Academy in Doha.

Armed with that knowledge and experiences gained, he was once again lured into action by O’Neill – this time the Ballymena man sounding him out about the role of elite performance director at the IFA in 2013.

Having been away for 27 years, the pull of home was stronger than ever. He couldn’t say no. The job was more complex than he had initially imagined but, finally back in Belfast, life was good.

Then one day, one horrible day, everything changed.

**************

“EVER since, it’s been the only thing on my mind.” Jim Magilton sinks back into his seat. The smile, the animated expressions, they’re gone.

It’ll be three years on April 28 since Jimmy Magilton died at his Glencolin Park home. His eldest son had been staying with him, the previous evening spent chatting into the small hours.

“He hadn’t been well, that’s why I was there.

“My dad was always my alarm call but that morning I walked into the bathroom, walked out and heard a thud. I ran into the bedroom and my dad was lying there. I tried to resuscitate him and couldn’t.

“The paramedic told me he was dead before he hit the ground, but seeing him and trying to save his life, that doesn’t leave you easily.

“For three years I’ve been battering myself. Could I have saved his life? Could I have done more? Why didn’t I see it coming? The night before we’d had a brilliant conversation about loads of things, then he goes to bed and the next day he’s dead.

“It’s hard to get your head around, and it had the most devastating effect because I lost a friend, a mentor, a critic… someone who played a major, major part in my life, every aspect of it.”

Magilton has begun to find a way through the fog, with the memories of his father now a force for good rather than a source of pain.

“It leaves a huge void. The moments when you need him, the moments when you would’ve picked the phone up, they’re still hard.

“But the only reason I’m coming out the other side is because of the hugely positive impact he had on me; I can’t allow that morning to take away from everything he gave me while he was here.

“Even when I was younger, my dad would have watched away from everyone. After a Gaelic or a hurling match he wouldn’t say a word to me. And I’d wait, and I’d wait. Maybe the Wednesday or Thursday, he’d say ‘well, what do you think?’ ‘About what?’ ‘About the game?’

“If it was a hurling match, he’d be saying ‘what about your left hand side; you lose balance off your left’. Or football: ‘You need to tackle. Where does it say in your contract you don’t tackle?’ To be fair, that carried all the way through my career - you didn’t need too much Persil for my shorts.

“Wee things like that come into your head… I think about him all the time, but I dwell on the positives now and keep my eyes forward, because that’s what he’d have wanted me to do.”

Which brings us to the here and now. The academy he heads up became Uefa endorsed last October. A hugely significant step, facilitating the establishment of Northern Ireland’s first full-time residential facility for young footballers, based at Ulster University’s Jordanstown campus.

Working with Milennials has forced Magilton to re-evaluate his own approach in a bid to bring the best from the talent at his disposal. It’s not 1986 any more, after all. But that doesn’t mean abandoning the principles that helped him shoot for the stars in his own career.

“See if you don’t have a work ethic and the right attitude, you’re not going to get anywhere. That is the case for every generation, no matter what. Nowadays, it’s instant gratification. Everything’s now, now, now.

“Growing up, we had an electric box behind our house and I used to spend hours upon hours in there with either a hurl or a football, working on my touch. I built ones of the same spec in Ipswich, two sweatboxes, and it was just rebound boards. That’s the game; how you pass it and how you receive it, on both sides.

“I did an exercise with the kids in the academy where I got the two best Fifa players to play. We would film it, then watch it back. Do it again, film it, watch it back - their eyes never leave the screen, but the fingers on their left and right hands are like a blur. They’re making decisions every millisecond.

“Transfer that to a football pitch; imagine you’ve worked that hard on your right foot and your left foot that you don’t have to look down, that you don’t have to think. That you’ve practiced so much you trust your skills.

“Yet you’re spending an average of seven hours a day between school and home on computers or phones - and you want to be a footballer? Time is your friend, your best friend; that’s something my dad always said.

“Don’t waste time.”

It will be a waiting game to find out who the IFA choose to succeed O’Neill, and there are some onfield matters to be resolved first – not least the upcoming Euro 2020 play-offs, and the possibility of a Northern Ireland-Republic of Ireland showdown to decide who goes on into the summer.

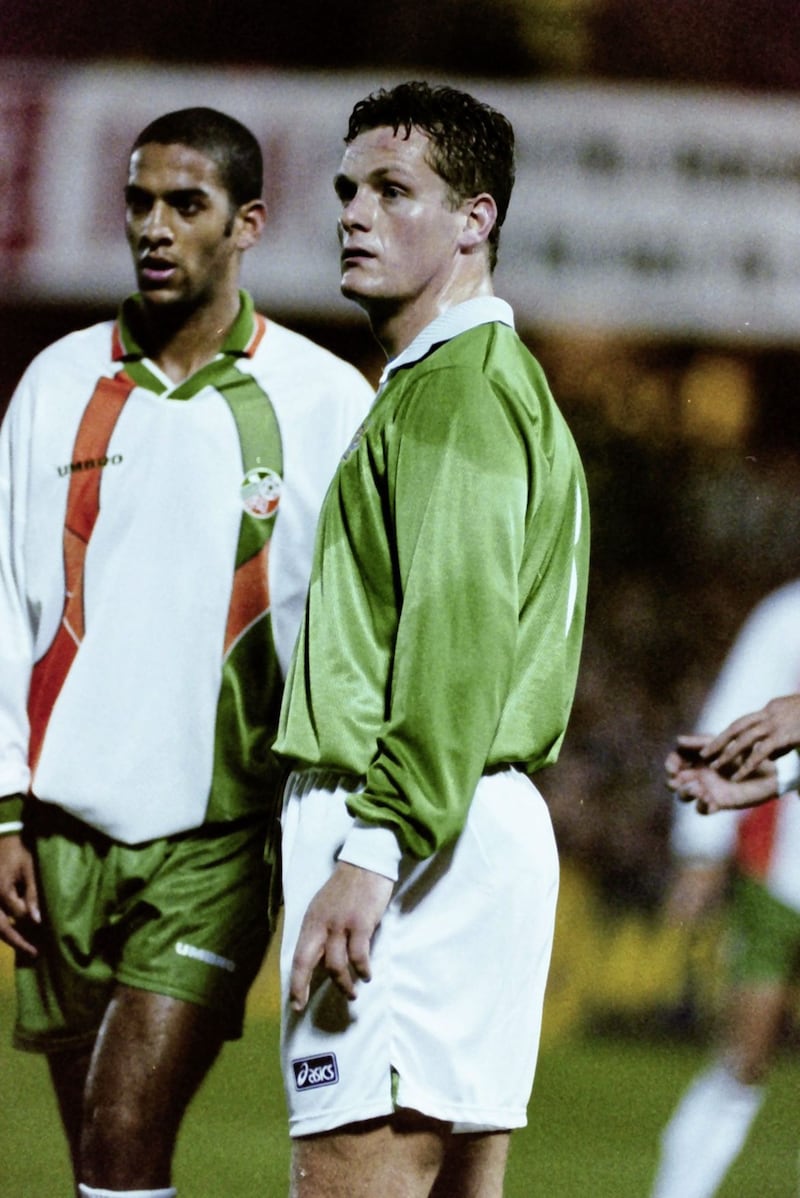

Having played in both 1993 encounters, including the infamous ‘Night in November’ when the Republic clinched World Cup qualification at Windsor, Magilton knows just how explosive those games can be.

“They were brutal… brutal.

“That was probably the most hostile environment I’ve ever played in. It was sort of like, let’s get the game done and dusted. I never approached any game like that but here was a lot had gone on in the build-up to the game.

“You try to shut it out. I was a professional footballer, so I was just trying to keep my head in the game - Roy Keane, Andy Townsend, Ray Houghton… I’d enough on my plate.

“But here,” he says, leaning in, “a Northern Ireland-Republic game at the stadium would be some night.”

At that, the smile returns and within a couple of minutes he’s off. People to see, places to be, not a second to waste. Hurricane Jim has left the building.