PAUL Ferris would have every reason not to be so chipper when the phone rings for the umpteenth time. A long haul of press interviews and media obligations have filled recent weeks, and they’re not over yet.

Tonight he is on UTV Life with Pamela Ballantine. Today and tomorrow at Eason and Waterstones in Belfast and Lisburn on a flying return visit to the land of his birth. There are various radio commitments too.

Ferris is promoting his second book, The Boy on the Shed, which hit the shops yesterday.

Despite the heavy loading, and a natural reticence to “push myself forward”, this is a moment he has looked forward to.

Not because he particularly enjoys the attention, or the travelling, or the phone calls, or the questions. But because only a matter of weeks ago he had his final session of radiotherapy, treatment for the prostate cancer he was diagnosed with in late 2016.

That came three years after he suffered a heart attack at 48, a time that first inspired him to commit pen to paper. So as the release date neared, it gave Ferris focus during some dark days.

“It’s been a tough old time,” he says.

“I wrote the book and sent the manuscript off in about November time, and I was having ongoing talks with the doctors. I’d had tests done, and then I got a diagnosis probably about three days after the manuscript was finished.

“I was in hospital the February after getting my prostate out when I got the offer from [publishing company] Hodder. When I was getting treatment then, I wanted to wait until it was all over before the book came out.”

So who is Paul Ferris and what’s his story?

A wonderkid plucked from the football fields of Lisburn by Newcastle United in 1981, at the time he was - at 16 and 294 days - the youngest player ever to don the famous black and white jersey.

His electrifying pace, a drop of the shoulder that bamboozled many a defender and the coolness of a killer in front of goal, Ferris was one of - if not the - first to be landed with the ‘new George Best’ tag.

He attended trials at Manchester United alongside another prodigy from this part of the world, Norman Whiteside (“an 11-year-old man”).

There are stories too of rubbing shoulders with a bubbly young Geordie who went by the name of Gazza. Of the day Newcastle United was turned upside down by the arrival of Kevin Keegan. Of watching enviously as Chris Waddle developed from a lazy looking kid into a world-beating winger. Of training under ‘Big Jack’.

Once a series of hamstring and knee injuries had brought his playing days to a premature end, he would retrain as a physiotherapist and eventually return to St James’s Park, working during the high times under Keegan and then the rollercoaster reigns of Kenny Dalglish, Ruud Gullit, Graeme Souness and Bobby Robson as anarchy at times descended upon the Toon.

Yet, for all the dressing room tales and juicy anecdotes – particularly about his stint on Alan Shearer’s Newcastle backroom team nine years ago - this is as far from a conventional footballer’s autobiography as you are likely to get.

Instead, it’s a wonderfully written account of a remarkable life, and a character shaped mostly by his experiences away from the beautiful game.

***************************************************************************

PATRICK and Bernadette Ferris raised their seven children in Lisburn, a Catholic family living in the Protestant Manor Park estate against the backdrop of the Troubles.

Paul, the youngest sibling, was five when their home was petrol bombed. Another night his parents were set upon by a Loyalist gang as they left a club. You don’t forget things like that.

“I wet the bed the next night,” says Ferris, recalling the scorched remains of the family home’s living room, “that was my first proper experience of the Troubles being in our house. I knew it was there but it was never in our house until then.”

Yet while such landmark events would inspire worry of one kind, it was nothing compared with the fear he felt every single day that his mother’s worsening heart condition would take her from him.

Forget the football, the falls, the highs and the lows, the deep loving relationship between Bernadette Ferris and her young son is the star of the show here.

It might have attracted a more traditional audience, especially in the football-mad city of Newcastle-upon-Tyne, to have related the title of the book to his days in St James’s Park’s inner sanctum.

But it wouldn’t have reflected what lies beneath the cover. The Boy on the Shed is Paul Ferris, so called because he used to climb onto the roof of the coal shed in his back garden from where he would watch his mother working in the kitchen. Sometimes for hours at a time.

He believed that God would not take her while he was watching.

And, even though she died 31 years ago, revisiting those childhood feelings was not an easy task.

“The stuff about my mother was painful to write. Painful to experience, but painful to write. My family reading that again will be tortured by that, but I had to write it.

“The passing was the dread at the end of it, but the thought of it was there with me from I was six years old. An Irish Catholic mother of seven, she had done it all before but she hadn’t done it all before and been fragile herself.

“I see that now myself with my own kids – the fear wasn’t all on my side after all.”

Word spread as he began to flourish on the football pitch, and soon Ferris was faced with the daunting prospect of leaving his sick mother and girlfriend – now wife – Geraldine behind.

Newcastle United wanted him to come over and, although he was keen to stay and finish his O-levels, maybe try and become the first member of his family to get into university, everybody told him it was an opportunity he couldn’t pass up.

Even Bernadette.

“For her to let me go to England at 16, when she wasn’t well, must have been awful.

“The pain of leaving home always lives with you, it never leaves you. Once you move away from your home, and you settle somewhere else, you never quite belong in either place and that’s the strangest thing.

“Newcastle in 1981 felt like a very long way from home. I’ve no qualms with anybody who told me to go, they all wanted the right thing for me, but the pain I felt and the feeling in my gut, that insecurity…

“It’s hard to describe that feeling when those doors close at the airport and you’re on the other side of it.”

Yet five years after arriving in Newcastle, during which time he was heralded by Kevin Keegan as the most exciting talent he had seen, it was all but over.

Injury after injury saw Ferris spend more time on the treatment table than on the pitch, and robbed him of the natural gifts of speed and mobility that had set him apart. At 21, he left St James’s Park for the first time.

If the same fate befell a young starlet now, they would at least leave the club with enough in the bank to ensure they were comfortable until another opportunity arose.

But Ferris slipped out the back door with barely a penny to his name.

“I came out with nothing at all. I remember calling at a friend’s house and his mum answered the door and when she asked what I was doing there, I told her I needed somewhere to stay. That I didn’t want to go home yet because I think I can still get fit.

“I left school at the start of my fifth year, so when I made my debut in May 1982 my friends in my class were doing their O-levels. If that happened now at Newcastle United or any football club, they’d have had you tied up to some sort of a contract that would’ve secured you for quite some time.

“Whether that’s the right way for football to go, I’m not sure, but after five years of being a professional footballer to walk away with nothing… football was a very different game then. It wasn’t in the stratosphere then that it is now.”

So, if he could wind back the clock, would he still board that flight to Newcastle?

“Would I do it again?” he asks rhetorically before a long pause for thought, “heart of hearts, I wouldn’t, no.”

***************************************************************************

THE days after the death of his football career were some of the most difficult. Bernadette’s passing in 1987 couldn’t have come at a worse time as Ferris struggled to make sense of an opportunity given and then gone in the blink of an eye.

Geraldine, his rock, was instrumental in the rebuilding process and a subsequent career in physiotherapy brought him back in touch with the world of professional football. It also brought him into contact with Alan Shearer, Ferris carrying out the medical as the £15 million man became the world’s most expensive player in 1996.

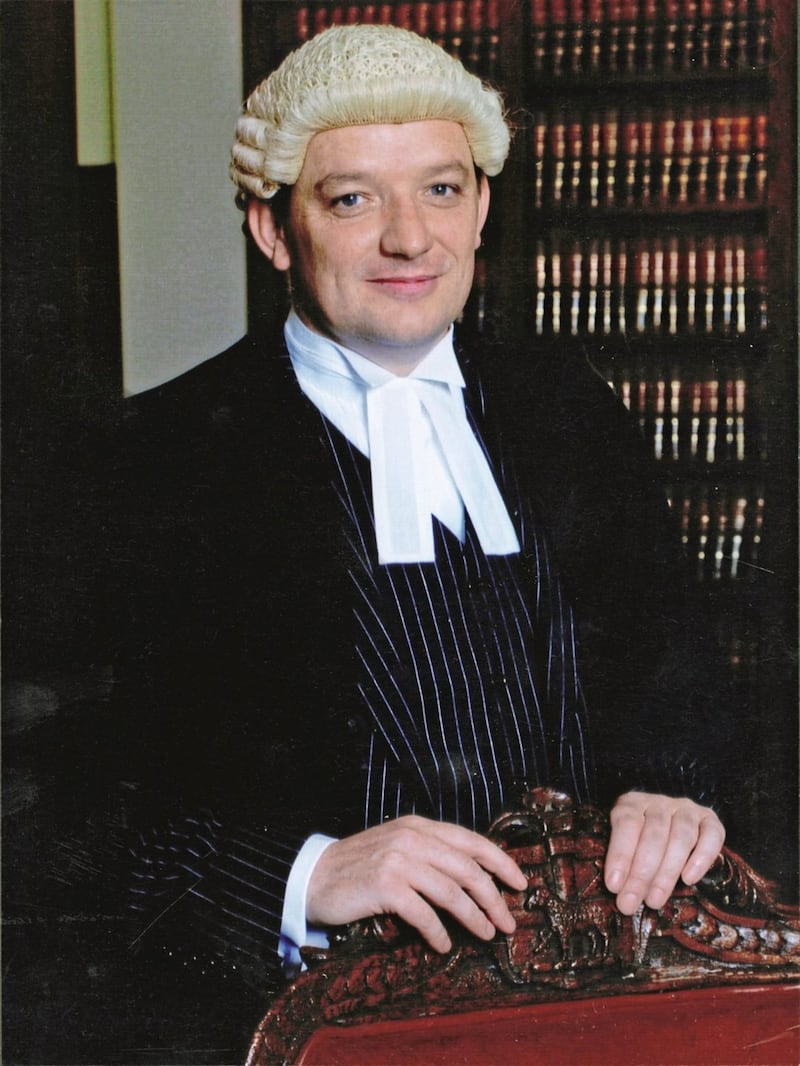

The pair became, and have remained, great friends, with the Newcastle legend writing the foreword for the book. Ferris turned his back on a career as a barrister after receiving a call from Shearer to join him at Southampton, a managerial move that never came to pass.

But when he was handed the task of saving the skin of his home town club midway through the 2008/2009 season, Ferris was the first person he called.

Now, through mutual friend Graham Wylie, both are involved in Speedflex, a company that offers high intensity circuit training – Ferris as chief executive, Shearer as a director.

Writing a book was always a pipe dream and, even when the manuscript was finished and sent off, he still wasn’t sure it would ever see the light of day.

“If you haven’t got a writing background, you’re a footballer, it’s very hard to get a publisher,” says Ferris, whose first book An Irish Heartbeat is - despite failing to attract a publisher - now being turned it into a movie by Dover Street productions.

“I decided to go ahead and write The Boy on the Shed anyway so my kids know who we are, how we got here, why we live in England, why the rest of the family live back in Ireland, why their mum and dad speak with an Irish accent.

“My granddaughter [Isla] was born last February; I watch her and think, in 10 or 15 years you’ll open it and see your name in the front of the book and it’ll be a precious thing.

“My big worry is that the person that might enjoy it the most might never pick it up; that it might just be pigeon-holed as a football book. I didn’t intend it to be that.

“If you find yourself lying in hospital, you’re not in the country of your birth, you’ve had a heart attack at 48, you look back and wonder ‘how did I get here?’”

Early reviews have been overwhelmingly positive. Despite the often heavy subject matter, there are also moments of real levity too, instantly identifiable with so many of our childhoods.

Nothing is off limits, the good and the bad handled with honest charm and sensitivity throughout. Yet, as the final chapter draws to a close, the reader is left to wonder where Ferris’s mind was at that time.

“I’ve felt the first chill of winter,” he writes, “I fear that it’s just around the corner for me.”

“I tried to finish the book on a positive note, but I thought the cancer diagnosis might be coming so the last bit of it, I felt very emotional when I was writing it,” he admits.

The heart attack has radically changed his approach to life too. Given his bleak family history, it had to.

“The only person who has been tested, as far as I know, is me.

“My brother Patsy died in his late 50s. Joseph had a bypass many years ago. Elizabeth, my sister who doesn’t smoke or drink, has had two stents put in, my brother Eamonn has had two stents I think put in, my sister Denise has had a stent, my brother Tony in New Zealand – who was an ex-professional footballer – has had stents.

“I had to radically change my lifestyle, which I have done, I had to radically change my diet, which I have done. I was doing quite well with that and then I got prostate cancer…” he says before bursting into laughter.

“I’m laughing but those two things, they just shake your confidence in everything. Where you didn’t have fear before, you have it. If I get a chest pain now I think ‘oh, what’s that?’ I have three boys and up to that point they think their dad’s invincible.

“But the best thing I can do, without living madly and having no life, is to basically live as healthy as possible.

“Thankfully, after all that, I’m starting to feel normal again.”

TheBoy on the Shed by Paul Ferris, published by Hodder & Stoughton, £20