CERTAIN sports, particularly individual sports, focus on acquiring levels of skills before new participants progress to the next level.

Visit the hundreds of leisure centres around the country any Saturday morning and you can observe swimming coaches teaching five- and six-year-olds how to breathe in water by turning their head sideways before they can progress from duckling to dolphin stages.

Or park up at a driving range to listen to the local pro dishing out pointers about head tilt or club grip.

These coaches do not focus on the length of the swim before a breath is taken or the distance of the golf drive if it is askew.

In many ways, our secondary school system operates in a similar fashion. For example, the general themes at GCSE level are expansions of first year mathematics theories and concepts.

If a child understands the foundations laid down at the start, they are more likely to absorb subsequent learning and make sense of it.

Another sport I marvel at is skiing. In a recent expedition to snowy slopes I was in awe at kids as young as five years of age as they zipped in and out of cones and could come to a halt effortlessly under the direction of a personal coach.

After an hour-long lesson they progressed to more challenging areas, with the sole focus being to improve their ability to stop immediately and to curve left and right with the skis with increasing tempo.

By afternoon, they were gaining confidence and by close of play on day five their progress was charted by their seamless transition through the ever increasingly challenging stages.

By comparison, older, less patient novices were trying to conquer the long steep slopes on their first morning, before they had learned how to stop. One helpless crash into the barrier was all it took to recalibrate their thinking.

As the coach, in broken English, put it: “You are very brave but you lack much skill.”

Those kids who persevered with the ‘S’ shaped turns, transferring weight onto the required inside leg, creating wide pizza shaped skis and so on were using repetition to master a technique and to acquire skills.

The actions became second nature to them. In other words, the specific aspects of each skill were so well honed that when they had to perform the skill during the descent of a steep slope or while avoiding hazards, they were able to do so with ease; automatically, voluntarily.

Performing the skill under hazardous conditions or at high speed did not faze these kids as they knew what to do.

The restlessly eager dads of this world (to whom many of us can relate) were much more erratic.

A short lesson to boost an overbearing arrogance and a small dose of bravado had only one certain outcome – embarrassment.

Despite dozens of descents down a moderate slope involving four turns and a controlled stop at the bottom, not one proved successful enough to justify safe passage to stage two.

With defeat almost admitted, a return to practising the basics on the beginners’ slopes reaped just rewards, but at a cost.

The only successful attempt was the very last one of the trip.

While returning to the hotel I scanned my Twitter feed to come across a thing of absolute beauty posted by GAA performance analyst Ray Boyne.

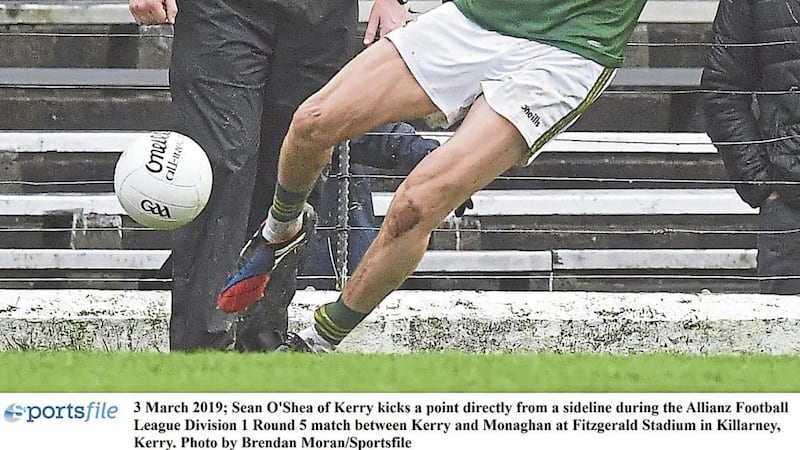

He combined a clip of Kerry’s Sean O’Shea kicking a score from a sideline on the ‘wrong’ side at the weekend with an almost identical sideline score by the great Maurice Fitzgerald.

The only difference was that Maurice Fitz kicked his score in Croke Park in an All-Ireland final, while Sean’s score was at home in Killarney in a game against Monaghan in which they were comfortable winners.

The key point, however, is that the skill levels on view from Sean O’Shea are magnificent.

When I see skills of this magnitude I ask myself how were they acquired? Was he coached on one-to-one at his club Kenmare, or by a family member or close friend who saw his potential?

We know he was an outstanding minor footballer but the difference he has shown at senior grade against the country’s top players and complex defensive systems has really brought him to the next level.

The secret may actually lie in the Kerry management team.

They possess the great man himself – Maurice Fitz, Kerry’s Mr Miyagi.

When a prodigy is coached by the best executor of free-taking and footpassing that ever graced the GAA field, it is likely that he too will excel.

It is my guess that a huge part of Maurice’s role is to coach Sean to perfectly execute the motor skills involved in free-taking or shooting so that his movements are automatic and perfect – so that he can do it under immense pressure.

For Sean, training is about improving muscle memory, not muscle mass.

Now that this young man has acquired the necessary skills, he has a solid base to which he can add further building blocks and lead his county towards success.