DOWN a rabbit hole the other day, I stumbled upon a document that underlined just how mad the GAA has become.

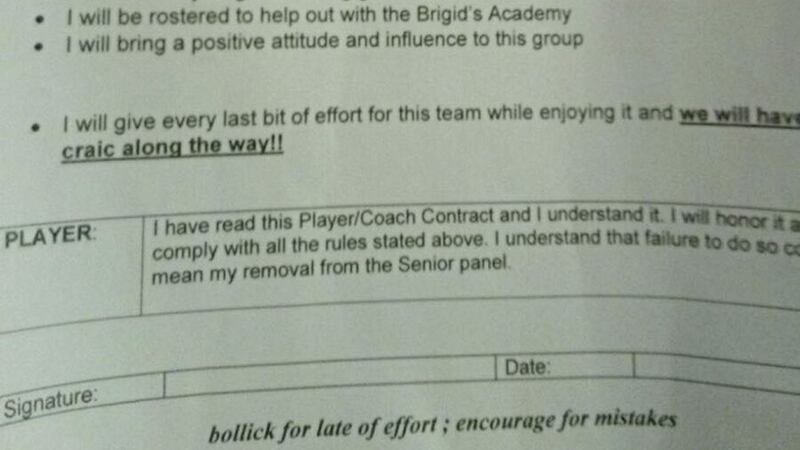

You’ll most likely all remember it. Ahead of the 2017 club season, St Brigid’s club in Dublin gave their adult footballers all a contract to sign.

In order to keep their place on the panel, the players had to agree to 16 different conditions.

These included (seriously):

- All holidays must be agreed in advance with management and taken only during breaks in the season.

- I will attend all club matches (when I am playing or not) unless I have the prior permission of management

- I will notify my coach in advance if I cannot attend training or a team-related activity

And my personal favourite:

- I will congratulate my team-mates chosen on matchdays. If I am not in the starting team I will encourage them on the pitch and be ready to give my all for the team if called upon.

Having the rules wasn’t the mistake St Brigid’s made. It was putting them down on paper and leaving themselves open the world getting a look.

When the world saw, it grimaced. It laughed. It scowled. It rebuked.

And yet it knew the truth, that this was nothing exceptional.

Almost anyone that’s ever set foot in a GAA changing room has been victim to something similar.

It is just about the worst way to manage a problem that didn’t even exist yet.

One of the chief obsessions among GAA managers is trying to micro-manage, and make players adapt and bend to their will.

The most time-effective way to do that is to employ a set of strict laws, and anyone who breaks them can clear off down the road.

Except it will, without fail, lead to one of two problems.

One of your better players will inevitably fall foul somewhere along the line. Then you, the manager, have to make a choice.

Do you send a 22-year-old out the gate of his own club, which you’ve probably come into from the outside and are getting paid to be there, telling him he can’t play because he took three pints on the Friday night?

Or do you ignore it, and thereby completely undermine yourself in front of the whole group?

You cannot command respect in a GAA changing room if you run it like a Tory government, where you have one rule for your star pupil and another for everyone else.

Either enforce the rules, or don’t have them.

GAA changing rooms have long since ceased to be such rational environments, though.

The Last Dance documentary has left many with a thirst for knowledge about the Chicago Bulls, and what it was that made them so great.

Phil Jackson’s book Eleven Rings gives a far greater insight than the Michael Jordan led-and-partly-directed documentary did.

Among his coaching principles was the idea that each player must discover their own destiny.

“One thing I’ve learned as a coach is that you can’t force your will on people. If you want them to act differently, you need to inspire them to change themselves,” he said.

The documentary shows the issues he had with Dennis Rodman, who bunked off to party twice at vital stages of the ‘98 season.

Jackson let him go, and welcomed him back.

The Bulls’ head coach, who went on to win five more NBA championships with the LA Lakers after being dumped by the Bulls after ’98, adapted himself to fit his players rather than the other way around.

His zen master Shunryu Suzuki’s philosophy that the worst thing you could do to maintain calm around an agitated subject was ignore them.

The second worst was trying to control them.

What we see of Jackson in The Last Dance is a man who wears his intelligence lightly. Smooth, calm, collected at all times.

Yet up until 1995, he would pace the line during games. It was only when he signed Dennis Rodman that he stopped.

“I noticed that whenever I got agitated, Dennis would become hyperactive. And if I argued with a ref, it would only give him license to do the same. So I decided to become as quiet and restrained as possible. I didn’t want to set Dennis off, because once he got agitated, there was no telling what he might do.”

One of his other philosophies was that sometimes you have to pull out ‘the big stick’.

His methods weren’t to scream and shout, but instead to make the Bulls practice in complete silence, or make them scrimmage with the lights out.

A favourite was to divide the players into two lopsided teams for a scrimmage and then not call any fouls against the weaker of the two sides.

“I liked to see how the players on the stronger team would respond when all the calls were going against them and their opponents were running up 30-point leads,” he says in the book.

“This scheme used to drive Michael [Jordan] nuts because he couldn’t stand losing, even though he knew the game was rigged…

“Sometimes no matter how nice a guy you are, you’re going to have to be an asshole. You can’t be a coach if you need to be liked.”

The secret is not that you must be perfectly calm.

It’s not that you must be tough.

And it’s not that you a set of strict rules that everyone must abide by.

Not only is everyone different off the field, but they’re different on it.

Good managers keep control by empowering and motivating the players to do it on their own.

Read the room, give people the direction they need and let them be themselves.

“To shine your brightest light is to be who you truly are.” (Roy T. Bennett)