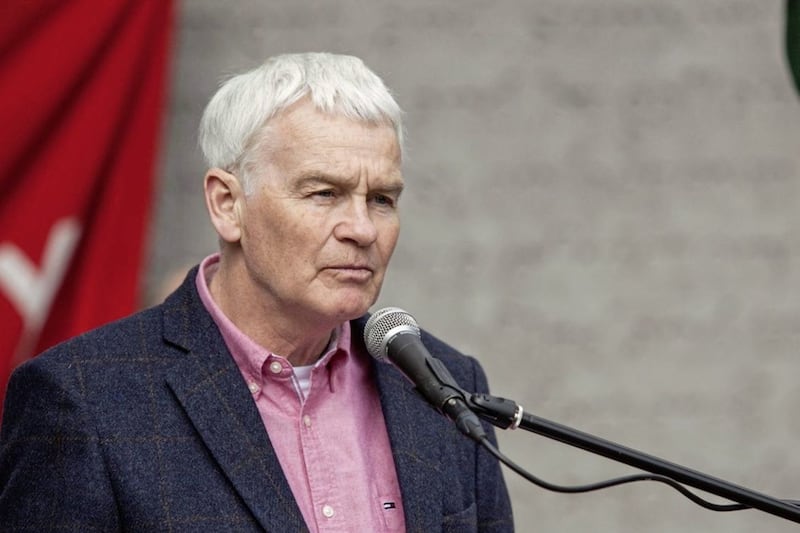

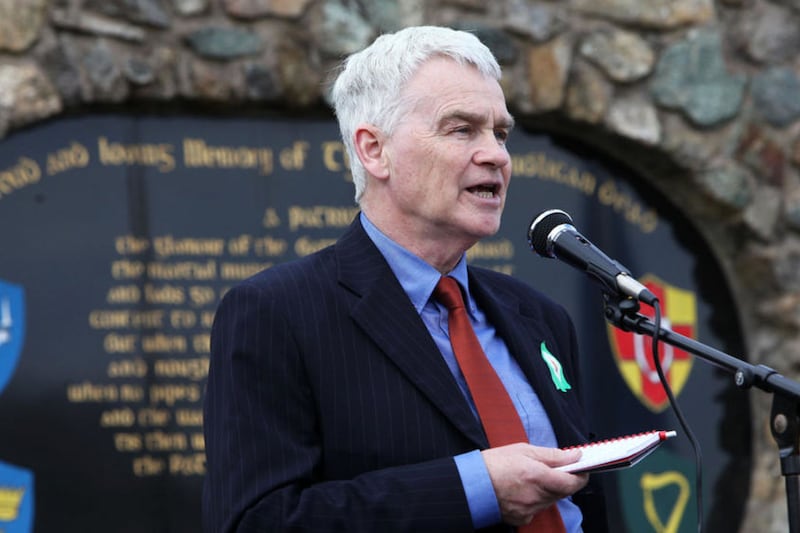

A prominent republican who took part in the 1980 hunger strike says he has no regrets despite coming close to death 40 years ago this week.

Co Tyrone man Tommy McKearney had been given just hours to live when the fast was finally called off.

The hunger strike was halted as another of those taking part, Sean McKenna, teetered on the brink of death.

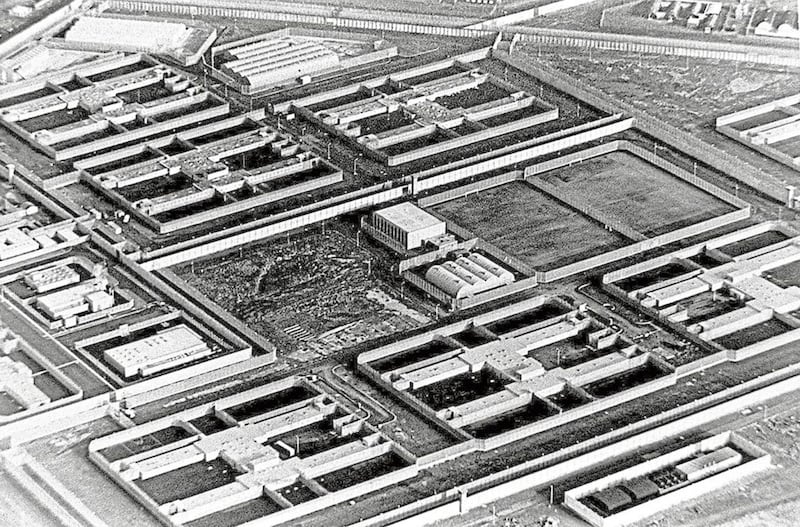

The protest, which included six members of the IRA and one INLA prisoner, lasted 53 days after being launched on October 27 1980.

Read More: Tommy McKearney recalls physical impact of hunger strike

It came four years after republicans had first refused to wear prison uniforms when special category status - de-facto political status - was withdrawn.

The British government's decision was seen as part of a policy to criminalise republicans, one which they fiercely resisted.

The bitter protest was launched after Belfast man Kieran Nugent refused to wear a uniform after being transferred to the H-Blocks from Crumlin Road Prison and instead wrapped himself in a prison-issue blanket to cover his naked body.

The 'Blanketmen', as protesting republicans became known, later started a no-wash protest, which included smearing excrement on their cell walls, as demands for a return of political status intensified.

The campaign escalated with the 1980 hunger strike as the prisoners issued five demands: the right not to wear a prison uniform, not to do prison work, the right to free association and to organise educational and recreational pursuits, the right to one visit, one letter and one parcel per week, and full restoration of remission lost through the protest.

Those refusing food, who all volunteered to take part in the protest, were: Brendan Hughes, Raymond McCartney, Tommy McKearney, Tom McFeely, Leo Green, Sean McKenna and John Nixon.

On December 1 three female prisoners held in Armagh - Mary Doyle, Mairéad Farrell and Mairéad Nugent - also joined the hunger strike.

Mr McKearney, who is originally from the Moy area, was convicted in 1978 of killing a UDR member and served 16 years before being released in 1993.

He immediately joined the blanket protest after being transferred from Crumlin Road prison, where he had been on remand.

The 68-year-old believes there were several reasons for the hunger strike.

"To the international community Britain was engaged in a struggle in Ireland that was deemed to be an imperial struggle, a colonial struggle," he said.

"That was something the British decided they would change the narrative of... by deeming the Irish struggle to be criminal and mafiosa-like, they were using prisoners as a sort of photo opportunity to show us wearing convict uniform doing menial tasks.

"For that reason it became imperative for us to resist that."

He said republicans also had one eye turned towards wider issues.

"It wasn't for creature comforts really, it was for the wider political context in which we were," he said.

"In some way it was a debt we owed to history, we owed to the comrades that had passed before us not to let that happen.

"And also with a view to the future, because ultimately no-one can support a criminal enterprise - whereas a patriotic battle for democracy and liberation is something that people will (support)."

Mr McKearney said the decision to launch the hunger strike came after every other tactic had failed.

"I believe that when the hunger strike came along that we found ourselves in a position where we had attempted practically every avenue we could think of between withdrawing co-operation, refusing to wear the uniform, to work for them, to do anything by way co-operation or consent.

"We were defined as non-conforming prisoners, and when every option to break the deadlock had ended we resorted to the last card any prisoner has - to hunger strike."

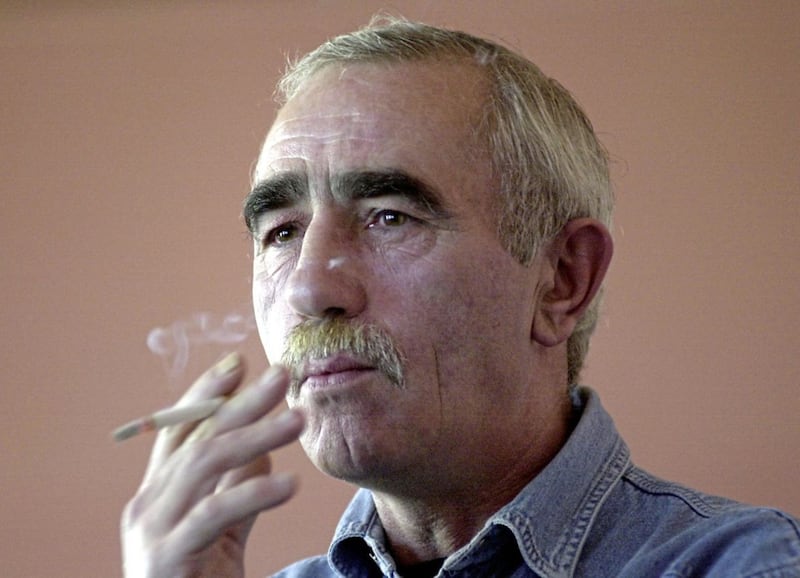

As Sean McKenna's life hung in the balance, Brendan 'The Dark' Hughes, who was in charge of the striking prisoners, took the decision to end the protest in the belief that an agreement had been reached.

Republicans later accused the British government, led by Margaret Thatcher, of reneging on its commitments.

Mr McKearney said as the hunger strike reached a critical point, mediators had suggested a deal could be reached.

"I'm not too sure of the actual details because the last couple of days I was critically ill," he said.

"What I do recall is there were very fierce, strong overtures made, strong suggestions made through intermediaries, that very significant movement would be made to address our requests and our demands."

He believes the British acted in bad faith.

"There was no movement at all," he said.

"We were willing to understand why they would ask for a type of face-saver such as changes being made over a period of time but we needed to see some evidence of it happening.

"There was absolutely none whatsoever so we have to conclude that the British were acting in bad faith."

After the hunger strike, Mr McKearney and the others who took part recuperated in the prison's hospital before being returned to the republican wings.

He described Brendan Hughes as a "very pragmatic man" who he had "enormous admiration for".

"With the benefit of hindsight I don't know if there's anything (more) he could have done," he said.

In the days after the hunger strike, spirits were bruised when authorities attempted to distribute civilian style uniforms instead of personal clothing.

Republicans, at this point led by Bobby Sands, decided to launch a second hunger protest which began in March 1981 and would result in the deaths of 10 republicans before it too was called off.

While Mr McKearney was fully supportive of those taking part in the second protest, he said he had concerns as the death toll rose.

"I was very concerned about the price the British were going to extract," he said.

"Once one person had died then you are into a long, lengthy, protracted struggle.

"Before the end I was very afraid it was going to continue.

"I wasn't so sure of how successful it could have been.

"I think we have to be very careful about that, how it ended.

"...I think we should have called a sharper end to it, but I suppose it's easy to be wise with hindsight."

As the 1981 fast neared its conclusion, campaigning Catholic priest Fr Denis Faul put pressure on some families to intervene to save the lives of several men after they fell unconscious.

"I think we shouldn't have allowed Fr Faul to effectively bring it to an end," Mr McKearney said.

"I still have to say that the IRA Army Council had the final authority on the initiative.

"At that stage we should have stepped in rather than leave the horrendous burden to families and leave it to a Catholic priest to take the initiative... It should have been the IRA."

However, he believes that the hunger strike "demonstrated beyond a shadow of a doubt that the republican cause was widely supported among the republican nationalist community in the north".

And, after 40 years, Mr McKearney says he has no regrets.

"Look, we did out best.

"There's no regrets.

"My regret is that we lost, not that we fought the battle."