I like and respect books that make me think. I particularly like those that make me rethink and reconsider some of my older certainties, while introducing me to voices I haven’t heard before. Even when those voices are saying things that make me feel particularly uncomfortable.

Susan McKay’s 'Northern Protestants On Shifting Ground' is one of those books.

Twenty years ago she wrote the hugely insightful—and similarly uncomfortable— 'Northern Protestants: An Unsettled People'. That journey from unsettled to shifting is something I’ve been observing and commenting on for years, too, although in my case it has been specifically about party-political unionism and the narrowing of electoral demographics between it and republicanism/nationalism and, since about 2017, ‘others’ as well.

For years I’ve been trying to put my finger on the precise reason for the growing disillusion with the Good Friday Agreement. Even though I voted for it I was aware, from around 2003, it was never going to deliver a ‘new’ Northern Ireland or ‘new’ way of doing politics here: but I could never find the words to sum up the core of my disillusion.

The poet Jean Bleakney, quoted in the book, does have the words: “…the GFA was never fit for purpose. It institutionalised a two-tribes mentality. What was not factored in was human nature, a particularly nasty algorithm hereabouts.” She voted for the agreement, but she’s right of course: and devastatingly so. She also summed up another issue at the heart of the book: “I felt the ground shifting…There needed to be a steadying of unionism.”

The problem with unionism is that it has difficulty with ‘steady’. It seems to prefer rolling around, or protest, or self-inflicted schism, or even full-blown internecine warfare. Most of which leads, inevitably, to lost votes and seats, which won’t, according to a quote in the book from the TUV’s press officer Sammy Morrison, be recovered ‘by lapsing into Derry syndrome (i.e. let’s all rally together, shut the gates and whoever isn’t standing with us is a Lundy)’.

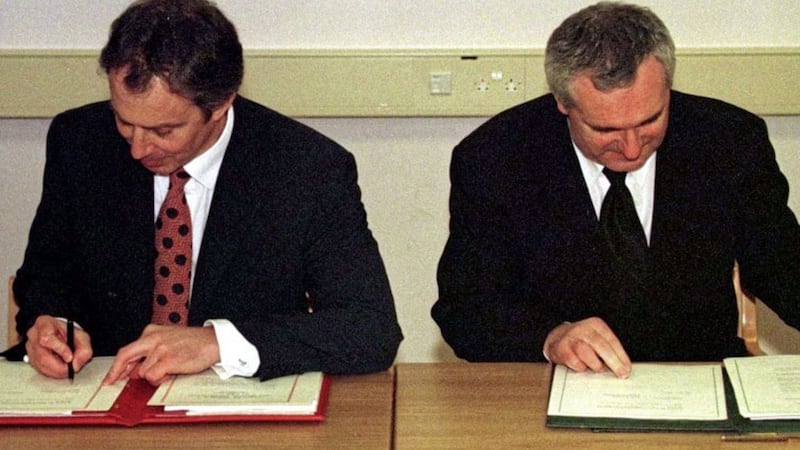

In my lifetime there have been a number of crises for unionists: the fall of Stormont (1972); Sunningdale (1974); the Anglo-Irish Agreement (1985); the ‘no selfish strategic or economic interest…’ doctrine (1993) and the GFA, which the majority of party-political unionism and Orange rejected in 1998. Each and every one of those crises (along with smaller hiccoughs along the way) had an impact easily recognised as unsettling to unionists. Yet there was no sense of a significant shifting in the thinking of mainstream unionism. No sense of an ultimate, final betrayal.

The interviews compiled in McKay’s book suggest there is now an important shifting of opinion. A recognition, if you like, by increasing numbers of those from a Protestant, unionist, loyalist background (the PUL community) that something very significant has happened to the relationship between Northern Ireland and Great Britain; and to the relationship between unionism and Britain’s political and media classes. Crucially too, to the relationship between unionist parties (particularly the DUP) and people who would usually have been expected to vote for them.

There will be unionists keen to dismiss the book as the work of someone who is ‘no friend of unionism…talking to people who were never really unionists in the first place’. That would be a mistake. Many of the voices in the book have been involved with political or on-the-ground unionism for years, while others have been astute observers of Northern Ireland post-1998.

And, as I said, some of the voices are entirely new to me, but no less important for that, including 16-year-old Rebecca Crockett: “I was born in 2002 so I wasn’t even alive in a time when there wasn’t a Good Friday Agreement. I’m the generation after the Troubles, the legacy generation. What I know about the Troubles is based on what people tell me. There’s always going to be two sides of it and it’s important not to be biased, to listen to every account, because everyone was affected by it and there were no good sides.”

I’ve noted before how diverse and often increasingly nuanced the various strands of the PUL are. Many of the voices in this book are reflecting on political realities post-Brexit and it’s those realities that explain the shifting. Not all of them ready to abandon their unionist/UK roots just yet, of course, but all of them shifting, sometimes even squirming on the ground they now find themselves.

‘Ulster’ unionism requires continuing majority support to safeguard Northern Ireland’s position within the UK. Each shift, each drift, each newly unsettled supporter or potential supporter, each new yard of difference between NI and GB—all of it makes it harder to sustain, let alone build the majority. Wednesday’s ruling on the protocol represents another shifting of the ground.

So, all in all, there’s a lot mainstream unionism could learn from this book.