WE may be in the throes of a global pandemic showing no sign of abating, but it would appear there is still time and space to be found for us to have a public argument about our troubled history.

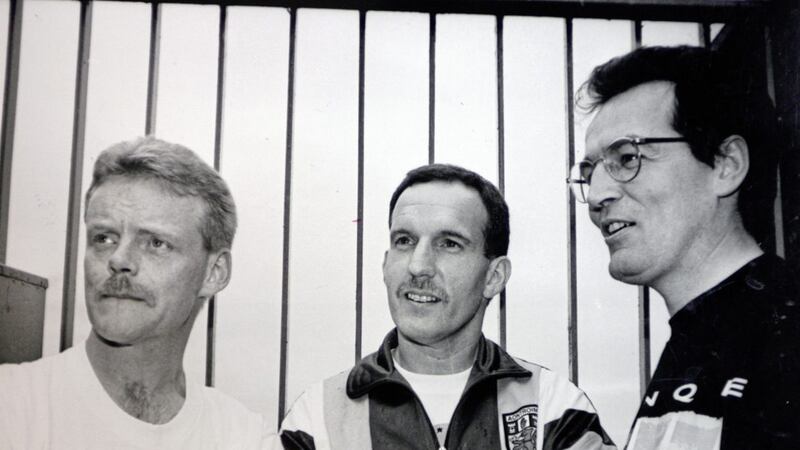

The latest spark of faux outrage, in a land defined by divided identities and sharply contrasting interpretations of the past, relates to a tweet from Sinn Féin's Gerry Kelly marking the mass escape from the Maze prison in 1983 by Republican prisoners.

Given that the former IRA prisoner participated in the escape and has for many years featured in panel discussions retelling the story of the largest prison escape in British and Irish history, that should not have been reason for much surprise nor comment.

In any conflict, prison escapes are regarded as particularly daring and risky endeavours. The audacious escape plan hatched and successfully executed by British prisoners of war in the Stalag Luft III camp in 1944 has been recorded for posterity as The Great Escape, celebrated in film where artistic licence allowed many of the prisoners to change nationality to become Americans.

There have been many prison escapes throughout the centuries that stand out in the pages of our history books, including Red Hugh O'Donnell's escape on Christmas Day in 1591 from Dublin Castle, where he had been held for four years after being kidnapped by the British.

A century ago, Éamon de Valera masterminded a remarkable escape from Lincoln Prison after smuggling a blank key into the jail inside a fruit cake which a fellow prisoner shaped into a master key, allowing the 1916 leader to unlock the doors and slip away to freedom.

In the 1870s, a prominent Irish republican living in exile in New York, John Devoy, received a letter from a Fenian prisoner serving time in a Western Australian penal colony pleading for help to escape.

Devoy proceeded to organise for a whaling ship, The Catalpa, to be sent half way across the world as part of a plan (which also involved a secret agent in Australia posing as an American millionaire) to steal the Fenian prisoners away from their shackles in Fremantle to freedom.

The unlikely plan proved a success, reinvigorating the Fenian movement in the US at the time.

Of course, there is another side to the Maze story. The 1983 prison escape may have been a significant landmark moment for republicans still recovering from the death of 10 hunger strikers two years previously, but it also cost the life of a prison officer who died of a heart attack during the escape, whilst several other officers on duty were seriously injured.

Unionist politicians, including the UUP's Mike Nesbitt, objected to the tweet and called for Gerry Kelly to be removed from the Policing Board on the grounds that it suggested he was not committed to non-violence and exclusively peaceful and democratic means.

This is a patently ridiculous charge implying, as it does, that deviating from a British/Unionist narrative of our pre-Good Friday Agreement past should be grounds for exclusion from a body created and tasked with holding to account and helping develop community confidence in policing more than two decades after that accord.

Ironically, remembrance continues to be a much more integral feature of unionist politics and culture than for nationalists, whether that relates to annually celebrating ancient battles that led directly to the Penal Laws; the foundation of a state undemocratically carved out against the wishes of the vast majority of Irish people; or commemorating British and loyalist forces involved in conflicts up to and including the most recent period.

It has been consciously woven into British identity in this part of Ireland in a manner contributing to unionism's exclusive appeal.

The real lesson of this episode is that it serves as yet another reminder of the need to develop a culture of thoughtful remembrance, balancing the sense of obligation and desire to pay respect and acknowledge the past with recognising the need to be sensitive to the perceptions of others.

Those with heads and hearts firmly focused on the future know that nation-building compels us to not just agree to disagree about our past, but to find a way to do so with respect.