WE are just over a month away from another commemoration of the 1916 Rising which began on Easter Monday of that year.

The official event in Dublin on April 10 will be attended by the great and the good from the political establishment. There have been plenty of other memorable days in Irish history but ceremonies recalling them don’t receive anything like the same recognition and attendance. Meanwhile, no doubt, the dissident republicans will commemorate the Rising in their own way elsewhere.

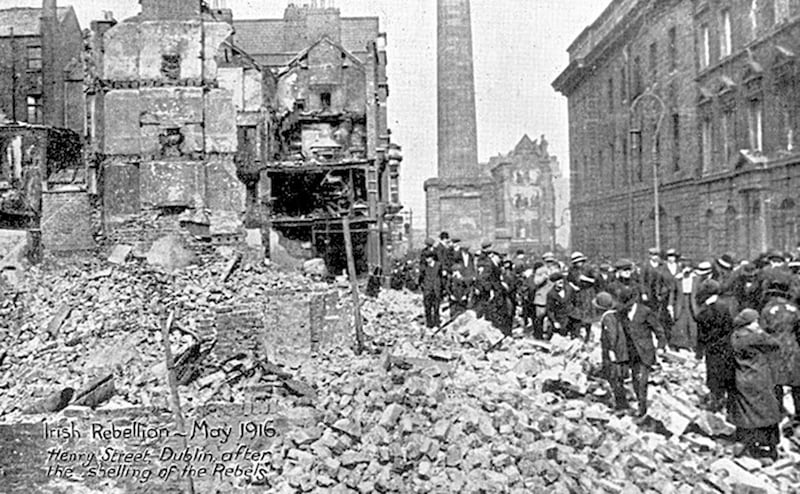

In overall terms, except for a blood-soaked ambush carried out on the Sherwood Foresters at Mount Street Bridge, the Easter Rising was a military disaster for the Irish side.

The First World War was in progress and the proclamation read outside the General Post Office referred to “gallant allies in Europe”, but a shipment of arms from Germany was intercepted en route and scuttled by its crew.

Broadcaster and author Joe Duffy tells us that, out of the 590 people killed during the Rising, 374 were civilian bystanders, compared to 116 British soldiers, 77 insurgents and 23 members of the police forces. Among them 38 children – aged 16 and under – were killed.

It is well-known also that, in addition to the British forces and Irish republican activists, there was an unofficial third army of looters who ransacked city-centre businesses for meat, jewellery, clothing, sweets and anything else they could get their hands on – even a piano – with 398 individuals getting fined or imprisoned afterwards as a result.

In light of all this, why is the Rising remembered annually on such a scale? How did such a comprehensive military defeat of the republicans turn into a political success which greatly advanced their cause?

The problem was the British response: they went too far in punishing the rebels. Historian Donal McCartney has pointed out that, for 40 years or so prior to the rebellion, there had been “a massive commitment” from the people to the Irish Parliamentary Party, which sought to achieve self-governing home rule for Ireland by peaceful means.

He continued: “It was not so much the rebellion of Easter week that completed the change in the attitude of the Irish people generally as its aftermath. Of the 90 people condemned to death for their part in the insurrection, 15, despite a mounting volume of protest, were executed.”

No doubt the British were outraged by what they regarded as a gross act of treachery in the midst of a world war, but had they felt able to refrain from putting Patrick Pearse and his comrades before a firing squad, the whole thing would have had far less long-term effect.

It was inevitable that the British military would be assigned to suppress the revolt, but, once the revolutionaries had surrendered, London should have played a restraining role. The Prime Minister at the time, Herbert Asquith, actually warned the British military commander Sir John Maxwell after Pearse and two other leaders had been put to death that “anything like a large number of executions would. . . sow the seeds of lasting trouble in Ireland”, but Maxwell kept on having people shot.

Locking up the insurgents even for a long stretch would no doubt have led to a fairly active campaign for their release but it wouldn’t have attracted anything like the same level of support for their cause.

The Rising is at the heart of republican psychology and, ever since, we have had situations where activists do their thing without worrying too much about its immediate impact on their popularity with the general public. Indeed that seems to be the mindset behind the actions of dissident republicans in our own time.

When Eamon de Valera was facing a sentence of death for his participation in the Easter Rising, few if any would have predicted that he would one day become President of Ireland, greeting his US counterpart John F Kennedy in a blitz of media coverage in June 1963.

The prospect of present-day republican dissidents heading up a 32-county independent state look even more remote than Dev’s chances in 1916 when it initially seemed the only future ahead of him was in front of a firing squad. However, if the Stormont Assembly stand-off remains in place for much longer, it won’t help in terms of sustaining a long-term peace. For that reason, all of those who want to ensure a lasting peace need to take a flexible approach to the difficulties that inevitably arise in a society with such a history of deep and frequently-bitter division and conflict.

One can’t help feeling somewhat envious of Scotland, since the debate about its constitutional future contains no apparent danger of violence.

At the same time, it is regrettable that the forceful and energetic Nicola Sturgeon recently announced her intention to resign after eight-and-a-half years as First Minister and leader of Scottish National Party. I met her once at a press conference in Dublin after a summit meeting of the British-Irish Council, set up as part of the Belfast/Good Friday Agreement, where she came across as an impressive and articulate politician.

In the 2014 referendum on Scottish independence, the No side won by 55.3 to 44.7 per cent. An increase of about five-and-a-half per cent next time would see the Scots achieving national sovereignty but the fact that the departure of the UK from the European Union meant that future relations between an independent Scotland and its nearest neighbour would become considerably more complicated if the Scots rejoined the EU.

It’s not just Northern Ireland that has had to pay a price for the Brexit referendum vote.