I am ten years older than my wife, an ideal age gap in many ways, reflecting the difference in maturity between the sexes.

Perhaps its greatest attraction, which becomes more apparent with age, is not needing to save for retirement.

My wife will simply come home from work one day to find me slumped over the keyboard, my lifeless form pressing down on the space bar, typing a final empty thought into the void.

It’s great to have one less thing to worry about.

There is also an intriguing quirk in our age difference, specific to this time and place. We are from the post- and pre-Good Friday Agreement generations, respectively. She was finishing her A-levels in 1998; I was already in my late 20s, with a mortgage and a long-term job.

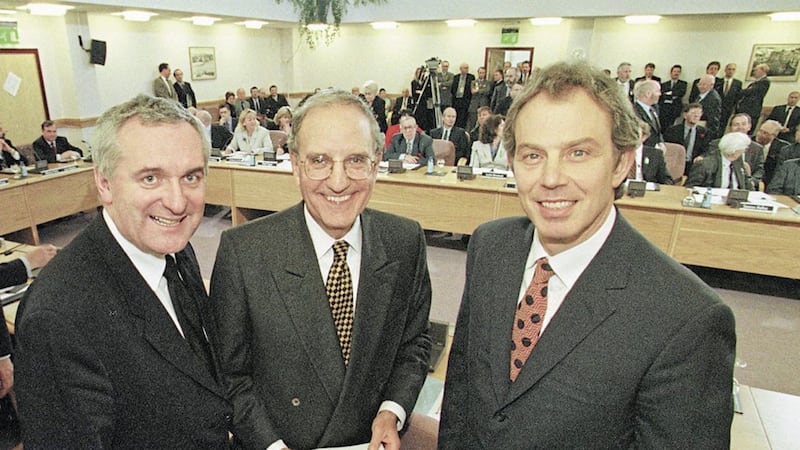

The agreement marked its 24th anniversary on Sunday. Reflections on this have naturally focused on the end of the Troubles and the record of devolution. However, the impact of the agreement I notice most in comparing myself to my partner is that people my age grew up expecting to leave Northern Ireland, while that mindset is completely absent among her and her friends.

The absence is relative, of course. Many young people still yearn to leave. What has changed is the deadening universality of it and the view that to stay is somehow to fail. Suffocating provincialism and a seemingly permanent unemployment rate of 15 per cent seemed more crucial drivers of departure than violence. Well into my mid-20s, conversation in my peer group was dominated by everyone’s plans to escape. To leave and come back, as I did, was considered unfortunate enough to require explanation.

I met my wife when she was 22, finishing an engineering course at Queen’s University. The lack of escape planning among her peers was immediately striking. At their age, Northern Ireland had felt to me almost as transient as a backpacker community, full of people moving on. Some of my wife’s friends did leave and have continued to do so but only through the organic progression of careers or relationships. None have gone for the sake of going, or felt they had no choice.

Because people have always kept coming and going, the transformation in attitudes behind it is difficult to see in raw numbers.

Belfast-based think tank Pivotal recently conducted surveys of students, graduates and professionals who have left or returned over the past few decades.

The samples were too small to be statistically meaningful but they did produce plenty of focus group-type anecdotes, to which I may add this article.

Pivotal’s respondents typically said they left due to the failures of Northern Ireland politics. What we do not know is how much the general readiness to stay has been increased by the success of the peace process.

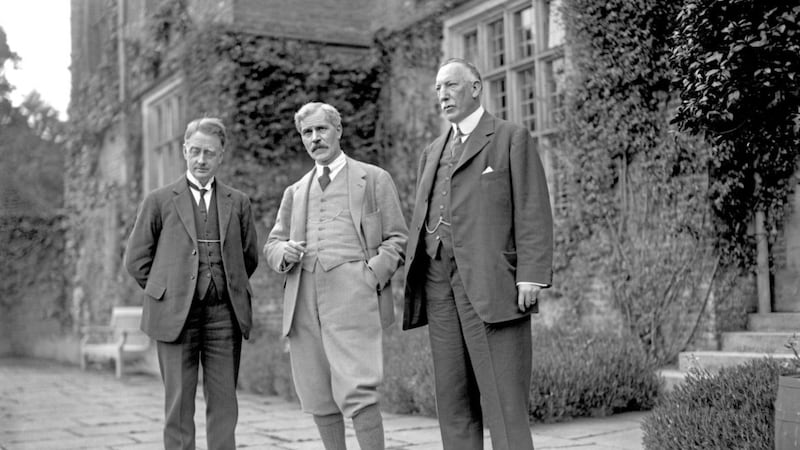

Generational factors were considered relevant and even decisive to peace during the 1990s. It was often noted that paramilitaries and political leaderships were entering middle-age and the age profile of the entire population was significantly older than when the Troubles began.

My wife believes she is a very particular “subset” of her generation, as the period from the ceasefires to the agreement coincided with her teens. She says it was “an extraordinary time to have your formative years” and an “intense experience of rapid change”, which has left her with “a lifelong interest in politics”, except when I am talking about it.

Now a college lecturer, she notices young people still share her expectation of a life here, yet they usually have little interest in Northern Ireland politics and make no connection between it and their choice to stay. In other words, they take it for granted. Does that make their choice more innate or more fragile?

The transformation is not unique to Northern Ireland, admittedly.

Two weeks ago, I went to visit a school friend in Manchester. His wife, who is our age, is from Meath. Her siblings and school-friends, like ours, are scattered across the globe. Had they been ten years younger, the Celtic tiger might have kept them at home.

The difference is that people from the Republic remain deeply aware they had a culture of emigration, which suddenly ended, for clearly understood reasons, with profound effects. They retain a concern of that progress being undone, as happened for several years after the 2008 financial crash.

We are bizarrely complacent about our equivalent achievements and risks. It could take less than the Troubles returning to see our children leave again.